Q&A: World food and fuel prices

- Published

There seems to be no end to the volatility in food prices around the world.

Extreme weather conditions have hit grain crops in the US Midwest and the western corn belt, prompting fears of food shortages and sending prices higher.

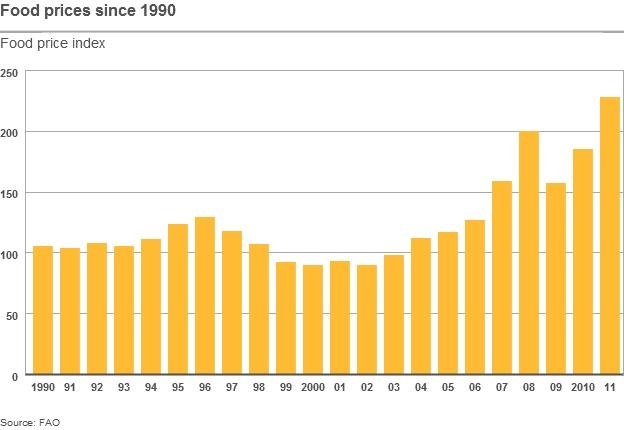

As a result, it has come as no surprise that the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) food price index saw a sharp rebound in July after three consecutive months of decline.

But the wholesale cost of food, as measured by the FAO, is still well below the record high hit in February 2011.

However, retail food price rises are still a major factor in consumer price inflation in the UK and around the world, giving rise to accusations that speculators are responsible for driving up the price of our weekly shopping basket.

In the meantime, oil prices have also fallen back since earlier this year, but forecasts of declining supply and rising demand suggest that they may not stay that way for long.

What are the main pressures on food prices?

Until this latest alert from the FAO, worries about food scarcity seemed to have eased since 2008, when soaring prices prompted riots and demonstrations around the world.

The FAO said in July that "the overall supply and demand situation in 2012-13 remains adequate".

It pointed to abundant supplies of rice, which is a staple in many Asian countries, as well as enough wheat and other grains available for export.

It added that world cereal production was expected to hit another new record this year of 2.4 billion tonnes, 2% higher than last year's record high.

However, with key crop-growing areas of the US facing their worst drought in almost 25 years, wheat, corn and soybean prices have been rising sharply.

Wheat prices alone have gone up 35% in recent months.

And the US Department of Agriculture has slashed its forecasts for corn production. It now thinks that this year's corn yield - the amount produced per acre - will be the lowest since 1995-96.

It predicts farm prices for corn will average $7.50-$8.90 per bushel, up sharply from its July prediction of $5.40-$6.40 per bushel.

Under US law, 40% of the corn harvest must be used to make biofuel, a quota which the UN says could contribute to a food crisis around the world.

What about the prices of other foods?

While US farmers are eyeing their frazzled grain fields in despair, their Canadian counterparts are anticipating a record crop of rapeseed, a key source of vegetable oil.

But further south, top sugar producer Brazil has been suffering delays to the harvest because of wet weather, leaving stocks low and pushing up prices.

And over in India, the world's second-largest producer of rice and sugar, there are fears that this year's below-average monsoon rains will reduce output after two years of bumper harvests.

"It is a challenge for farmers to meet the same performance as in the last two years," Indian farm minister Sharad Pawar said last month. "This year, the monsoon is playing hide-and-seek."

What about speculators?

Indian food prices have been soaring because of the late monsoon rain, says the BBC's Yogita Limaye in Mumbai.

FAO director general Jose Graziano da Silva has pointed the finger firmly at speculation on the financial markets, saying that "more understanding is needed" about its impact on food price volatility.

"We are not talking about speculation related to price discovery and the normal functioning of the futures markets," he said.

"We are talking about excessive speculation in derivative markets, which can increase price swings and their speed.

"Excessive food price volatility, especially at the speed at which they have been occurring since 2007, has negative impacts on poor consumers and poor producers alike all over the world."

The Economist Intelligence Unit has also noted instances in which speculators who treat commodity shortages as an investment opportunity have "helped exaggerate" price rallies.

The World Development Movement (WDM) is keen to curb this betting on prices.

It wants greater regulation of the buying and selling of futures contracts, which are an agreement to sell a commodity at a certain price at a set time.

These were created to reduce uncertainty, as the producer has a guaranteed price and the buyer secures the goods they need. It is in effect a way for both sides to reduce the risk of doing business.

But the WDM and others think that trading these contracts like stocks and shares is pushing food prices even higher, to the detriment of the poorest people.

And what's happening to the price of oil?

The price of a barrel of oil on the London market has retreated since April, when it was trading at about $125 a barrel. Prices are now not much above the $110 mark.

However, political tensions continue to affect some oil-producing countries in the Middle East.

Iran is still threatening to block shipping via the Strait of Hormuz, through which up to one-fifth of the world's oil currently passes, unless sanctions against it are lifted.

Underlying this uncertainty is the rising demand for oil.

Analysts point, in particular, to the thirst from China for energy to fuel its factories and power thousands of new cars.

Like food, it is difficult to escape the impact of the rising crude prices.

It not only directly affects the cost of fuel and energy, but also feeds into the prices of other goods by raising the cost of production and transport.

As many economies around the world struggle to cope with a painful global downturn, wages are not rising to keep pace. So many are really feeling the squeeze.

- Published13 July 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published17 May 2012

- Published14 May 2012