Can robotics change the future of a nation?

- Published

Building the future: Does robotics hold the key to building a generation of innovative young Ugandans who can find solutions to some of the country's technology problems?

"I want to go deeper into machines - automatic machines. I was inspired by him when he came to school - so I had to find ways of getting in touch with him."

Victor Kawagga is a softly spoken young man, but his quiet manner can't counter the eager sparkle in his eyes and the passion he has for the machines he's surrounded by.

The bedroom of this house in the Ugandan capital Kampala has been converted to a home lab, and the young people hard at work here are building robots.

The 'him' he is referring to is Solomon King, the 29-year-old technologist and businessman who takes robotics into the classrooms of Uganda as the founder of Fundi Bots.

"He stalked me," laughs Mr King, bending his head slightly to fit his lanky frame into the doorway.

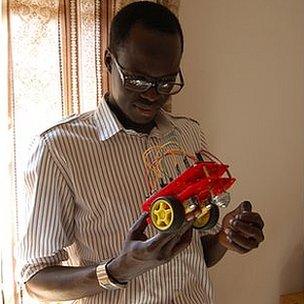

Victor Kwagga holds the robotic's club's latest project, made entirely from local found materials. One wheel is complete, the team is working on the second. They expect it to take two months to complete the robot

Now Victor and 12 others spend their days at Mr King's home working on projects that involve using locally-sourced materials - in this case bike chains, spokes and the like - to build a robot that will move, sense water and light, and transmit signals to a receiver.

Victor wants to go to university - but this is Uganda, and for ordinary people higher education is expensive.

Solomon King, the founder of Fundi Bots, holds one of the kit robots they use at their robotics camps

The government-funded scholarships don't always go where they should. Fundi Bots - fundi is Swahili for maker or artisan - is his chance to learn about a world that might otherwise have been denied him.

I, robot

The everyday applications of robotics might escape the casual observer but, Mr King says the science has clear and practical applications for life in Uganda.

"Fundibots for me is like a way to build a new breed of thinkers and innovators," he says.

"The thing about robotics is it's one discipline, but there's a million sub-disciplines in it.

"I keep telling the students that when they've finished their first robot, they've learnt about electronics, they learnt about logical thinking, they've learnt about programming, mechanics, you've learnt a bit about biology, you've learnt popular science."

Ivan Agaba (front) wants to be a doctor: "I watched a movie and I saw how machines would operate in a medical room, and I was like, how do these guys manage to come up with such stuff."

"By the time you have a small army of people who have done robotics at some point in their lives, their mindset is no longer the same. They look at solutions from a creative angle."

This certainly seems to be borne out by the young people in this room.

"Basically what I like to do is create something," says Arnold Ochola.

"For example we have a power problem here in Uganda. So if I can come up with something that solves that I would really be proud of myself."

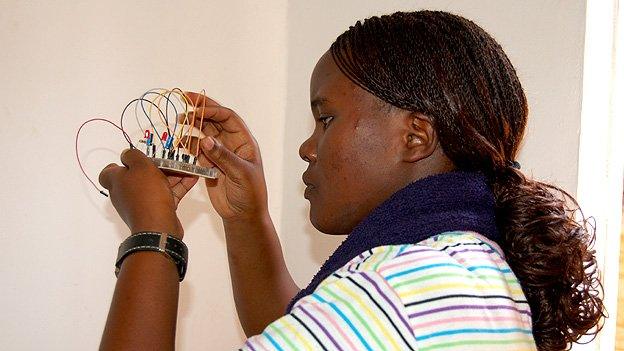

Phiona Namirimu wants to be an aero mechanical engineer: "Right now I'm building things, so if I hope to build a plane someday, I think I start small and grow big so this is part of it."

Mother of invention

Betty Kituyi Mukhalu of Café Scientifique is the Fundi Bots coordinator, and remembers their first school visit: "He came with this little robot, Nigel. Nigel walked, and it was so marvellous to see someone from our own environment having made that."

Mr King says that growing up he was always 'tinkering', pulling things apart and putting them back together, or making something new.

Betty Kituyi Mukhalu: "[Solomon] talked about having a lab at home in his spare bedroom. That just charmed me."

"Back then most of us kids made our own toys, we'd make wire cars and all sorts of gadgets from old tins and bottles and stuff.

"I was always the one trying to make mine move on it's own as opposed to being pulled along by a string."

Robotics is a 'solution waiting for a problem' says Mr King.

"Long term there's industrialisation which is maybe a bit too grand, but on the small scale we have small scale solutions - maybe a small windmill in a village that generates power. Maybe a home-made mosquito repellent system. That's what I'm trying to do with the kids.

"I think my biggest passion is to see Africans solving Africans problems.

"A lot of the time we get assistance from abroad and when you bring a solution down here it doesn't quite work, because it's different mindsets, different environment, just the weather conditions alone are strange.

"That's what Fundi Bots is about. It's called Fundi Bots but it's almost less about the robots than the process of building the robots."

Mr King feels that agriculture in particular could benefit from robotics

Offline connections

Technology is helping improve the prospects of students in other ways.

Connectivity and bandwidth are on-going problems in most emerging markets, and Uganda is no different.

Despite the gradual roll-out of fibre-optic cable, and the spread of 3G - and soon 4G - connections some areas can be patchy, and the cost of transferring large amounts of data is high.

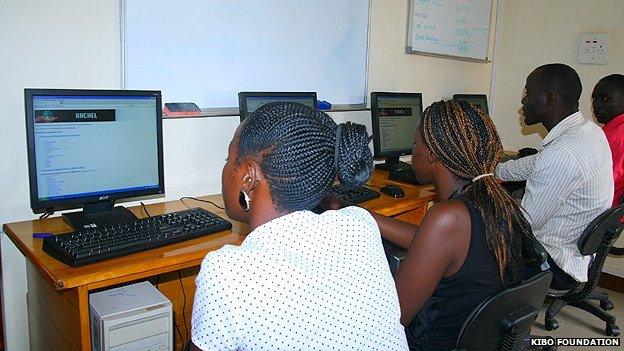

The Remote Areas Community Hotspots for Education and Learning (RACHEL) repository is a database of textbooks, online resources, MIT Open courseware and other sources. The content is housed in a server - a PC harddrive - and available offline.

It is the creation of a non-profit organisation called World Possible, and in Uganda the content is distributed by their partners UConnect.

KiBO foundation students using the RACHEL repository. The KiBO foundation provides intensive courses in IT to young Ugandans.

"We don't have one textbook per child here as you do in Europe," says UConnect's Daniel Stern.

"The teacher will have the textbook and the students will copy what the teacher puts on the blackboard, so to suddenly have access to an offline Wikipedia where everything is immediately clickable there's a very high level of engagement."

UConnect supplies equipment - including solar-powered computer labs in rural areas - and the repository to schools, universities, hospitals, and prisons.

Virtually there

But what if you don't have access to a classroom?

Andrew Mwesigwa believes he has the answer. He is the founder of a virtual college - Universal Virtual Content - Uganda's first home-grown online-only course provider.

Universal Virtual Content's Andrew Mwesigwa has plans to expand to smartphones and tablets

"People here like to be interactive, and go into a class and see a lecturer teaching and ask questions.

"I felt I should get a tool that would really be interactive so they get to feel as if they are in a real class."

Training software from the US, and a digital pen that lets teachers share as they write while talking to students, has let him create an interactive experience that uses less bandwidth than video-conferencing. It's a simple solution but one that Mr Mwesigwa believes can work.

"Currently we are targeting mostly professionals around accounting courses, because they are quite popular and someone with accounting can easily get a job."

The big problem has been convincing government agencies to accredit their courses.

"They're used to infrastructure, buildings, whereby you want to see a classroom, and that's what their forms require. When you say my school is purely virtual they don't understand."

Mobile learning

The ubiquitous mobile is being used help students prepare for the all-important Kenya Certificate of Primary Education - the KCPE.

This determines the secondary school a child will go to, effectively dictating the path they're likely to take in life.

Children choose a subject by texting a code. Quizzes consist of five questions - and the correct answer plus an explanation is sent back. Progress is stored and used to track children's progress

A Nairobi start-up has created a service where pupils can subscribe to to take quizzes via their mobile phones. The questions are sent by text message.

"Initially our target customers were the kids who are isolated in the slum areas and can't get access to the internet and reading materials," says Chris Asego, MPrep's operations director.

"This is for families who are not doing too well and can't buy textbooks. That was our target market but as we grow we cover all bases, the rich, the poor, the middle class."

Schools can subscribe to MPrep, to compare students progress against other schools

The award-wining company is still fairly new - but according to Mr Asego growing.

"At the moment we have about 4000 users, and that's for a period of about three to four months so we're doing pretty well," he says.

In Kampala, Fundi Bots is gaining supporters - they were recently the recipients of a Google Rise grant.

The aim is for every school in Uganda to have a robotics club, where students can exercise their curiosity - and find problems waiting for solutions.

For Mr King, this is the realisation of a dream.

"When I was young, I sort of made a vow to myself, if I ever grow old and if I ever have the money I would open up this huge facility for kids like me back then, where they could just walk in and say I want to build this, I want to do this, and everything they needed was there."

He's nearly there.