Past philanthropists: How giving has evolved

- Published

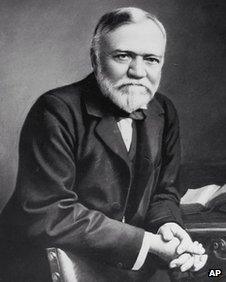

Andrew Carnegie paid for thousands of public libraries to be built

"To promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world" and "to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge and understanding".

Two bold visions from two men who wanted to use their vast wealth to do good.

John D Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie made their money in the oil and steel industries respectively, but both of them wanted to make sure their money would make an impact on society long after they were gone and set up their own philanthropic foundations.

Indeed, according to Carnegie, "he who dies rich dies disgraced".

A century on from when they were created, the mission statements of the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation reflect the areas in which their founders wanted to make a difference - in Rockefeller's case healthcare and in Carnegie's education.

But although those vision statements were bold, they were also very broad in their scope, leaving how one goes about achieving those visions open to interpretation.

Trustees

Often when past philanthropists endowed a large sum of money to a foundation, they had the broadest objectives in order to get legal status, says Dr Beth Breeze from the Centre for Philanthropy at the University of Kent.

"But because the objectives were so broad, it's then the job of trustees to interpret it when the founder dies," she says, adding that it can be a bit of a guessing game.

Luckily for the Carnegie Corporation, Andrew Carnergie recognised that "conditions upon [earth] inevitably change" and did not wish to tie future trustees down to certain policies or causes.

"I [give] my Trustees full authority to change policy or causes hitherto aided, from time to time, when this, in their opinion, has become necessary or desirable. They shall best conform to my wishes by using their own judgement," he wrote in his letter of gift to his original trustees.

So although the corporation still has a heavy focus on education, and has moved from building libraries in Carnegie's day to expanding higher education and adult education, it also has programmes in other fields, for instance aimed at promoting international peace and the advancement of minorities.

Changing world

That is not to say that philanthropists of yesteryear would not be surprised by the way the agenda for issues they were interested in may have changed over time.

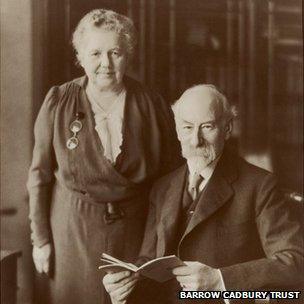

In 1920 Barrow Cadbury, grandson of the founder of the Cadbury's chocolate company, and his wife Geraldine set up the Barrow Cadbury Trust to promote social justice. Today, the Trust is chaired by their great granddaughter Ruth Cadbury.

Quakers Geraldine and Barrow Cadbury set up their trust to campaign for social justice

"Barrow and Geraldine were Quaker industrialists. Quakers believe in the intrinsic equality of all people and in the responsibility of all people to give public service and care for others," Ms Cadbury says.

"The world has changed dramatically over the past century and some of the projects we now support might be surprising to Barrow and Geraldine."

Sara Llewellin, the Trust's chief executive, points to the Quaker support for gay marriage and the Trust's willingness to support work promoting lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) equality.

"While neither [Barrow nor Geraldine] lived even to see homosexuality legalised in the UK and certainly not to see the birth of a rights movement on the issue, we are confident they would have been supportive of that movement were they alive now," she says.

Like Carnegie, she adds that: "Barrow wrote the trust deed in such a way as to give trustees of the future absolute discretion."

Increasing opportunities

As current trustees of these large foundations and trusts are keen to point out, they strive to carry on their work in the same spirit as their founders.

But looking more generally across the field of philanthropy, there are some broad themes from a century ago that are still valid today, according to Leslie Lenkowsky, clinical professor of public affairs and philanthropic studies at Indiana University.

"In terms of the substance of [past philanthropists'] giving, there remains a lot of interest in increasing opportunities," he says.

"Carnegie says it is the duty of the wealthy to allow other people the opportunity to be wealthy. [Bill] Gates has also made that very clear."

He also cites the desire to make giving as effective as possible. Rockefeller, who from his very first pay cheque made regular church donations, was always a tither, says Prof Lenkowsky.

"But when he got so much money, he felt he should make his giving better than just giving to this or that church."

A commitment to rely on experts and the collection of empirical data, pioneered by the English philanthropist and social researcher Charles Booth - who carried out surveys of the poor in London in the 19th Century - also prevails.

Misnomer

But clearly not everything is the same as it was 100 years ago.

The biggest change affecting the older foundations has probably been the growth of government, with state funding now covering areas that they weren't previously, such as health and education.

"Nowadays people call philanthropists the third sector but in many ways that's a bit of a misnomer," says Beth Breeze. "[In Victorian times] they were the first sector. If they didn't build a hospital no-one would."

She points to how the funding of water has changed over the years as an example of how funding in different areas can evolve: "In centuries past the water pump would be funded philanthropically, then it became state funded, and then privatised."

With government cuts now taking place across Europe and the US as countries attempt to repair their economies, there is a chance that charities who see their funding dry up turn to the "third sector" to step in.

But Dr Breeze says what philanthropists don't want to do is step in and fill the gap, funding something just because the government stops. They want to fund something new.

So what will the philanthropy of the future look like?

Prof Lenkowsky believes we are already seeing more big donors who are choosing not to use foundations, sometimes feeling that big foundations can be too bureaucratic.

Some might be choosing to give directly, while others are looking at social entrepreneurship - using business models to tackle problems in society.

This does not mean that the likes of the Carnegie or Rockefeller foundations will disappear, because they are permanently endowed, but we might not see so many new ones cropping up.

"I think we're going to continue to see a mixture of things," Prof Lenkowsky says.

"We'll see more [people] involved in direct giving, more looking at business and charity. [But] I think the Gates Foundation will be the last big foundation for a while."