Budget 2013: Radical options for the UK economy

- Published

Is this really as good as it gets?

Or could there be a yet-to-be-tried miracle cure for our economic malaise?

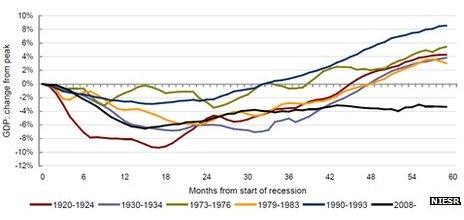

We are currently in the longest depression - with the economy failing to recover to its previous peak level of output - since before the 1920s, external.

At 7.8% of the workforce, unemployment remains uncomfortably high five years after the financial crisis. And this figure masks an even grimmer reality, external in which many of those in work have had to accept lower pay, part-time work and temporary contracts as they and their employers struggle to make ends meet.

Average household incomes in the UK have suffered an unprecedented period of decline, external dating back to before the financial crisis, with poorer households hit hardest.

This is our worst economic performance in a very, very long time

Can't spend, won't spend

At the heart of our malaise is a massive overhang of debt left over from the property boom years, particularly the mortgages taken on by young families, commercial landlords and small businesses.

That debt built up in the decades before 2008, reaching five times our yearly economic output, and has not gone away since, external.

It has become an albatross around our collective necks.

Those with the debts - not least the government - are reining in their spending in order to get their finances back under control. These are the "zombie" businesses and households who are struggling to stay afloat.

Unfortunately, those without any debts also have little incentive to increase their spending.

Why, for example, should big businesses, sitting on huge piles of cash, external, invest in more production when the demand for their existing output remains so tepid?

Why should the baby-boomers, who benefited most during the boom years when the value of their old family home rose and rose, increase their spending now when their children face such hard times, and when the annuity income many can expect from their pensions has fallen to an all-time low, external?

All of which brings us to the central problem: If nobody wants to spend more, then nobody will earn more.

And if nobody earns more, our debts will not go away, no matter how hard we try to economise. It is a vicious circle.

But before you reach for the happy pills, read on.

Because there are a number of novel ideas currently doing the rounds at the Bank of England and the Treasury for how the UK could break out of this circle:

Negative interest rates

Promising to stoke inflation

Helicopter money

Old-school public works schemes

A debt jubilee

Option 1: Reversing the charges

Penalising money left in a bank account may lead people to hoard cash or gold

Most economists will tell you the Bank of England's biggest headache is that it is running out of bullets.

Normally, when the economy gets into trouble, so long as inflation is under control, the central bank cuts short-term interest rates.

Economics textbooks say that doing this will discourage people from holding cash and make it cheaper to borrow and invest. In other words, it is a good way to get people and businesses to go out and spend more.

This time round, the economy has got itself into so much trouble that the Bank has cut interest rates as far as it felt safe to do so. Rates have been stuck at 0.5% since March 2009, the lowest since the Bank began setting interest rates 320 years ago, external.

So the Bank turned to Plan B - the much-vaunted and little-understood quantitative easing, or QE.

What this amounted to was the Bank of England buying up government debts, paid for with newly created "money".

The aim of QE, external was to push down longer-term borrowing costs, and to push up the value of financial assets, most obviously the stock market, making everyone feel richer.

How low can you go?

Shares in London have certainly risen, with the leading FTSE 100 index hitting a five-year high this month.

But, four years and £375bn later, QE seems to be running out of juice. The fall in long-term interest rates does not have much further to go, external.

Frustratingly, a lot of the newly-created money seems to have got stuck in the banking system. Banks have not been keen to lend it out. It has just sat there doing precious little.

That is because the banks, whose easy lending during the boom years created much of our debt in the first place, are trying to slim down, and are in no hurry to increase their lending.

What's more, to some extent QE has been counterproductive, because it has resulted in lower pensions for many baby boomers, hardly a way to boost spending.

All of which has led some economists to revisit plan A. Why not cut short-term rates even further?

The Bank's immediate concern with going below their current 0.5% was that it would hurt banks and building societies, many of whose existing loans earn interest directly linked to the Bank's rate.

The Bank of England does not especially care about how much profit these lenders make. But it does care that if their profits are squeezed too much, then they will simply cut back on how many new loans they provide to the rest of us.

In recent months, however, this particular concern may have receded, thanks to another innovation of the Bank of England - its Funding for Lending scheme. This pays the banks to provide more loans to homebuyers and small businesses, although the jury is still out on this one.

If the scheme does succeed, it should open the way for the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee to cut interest rates all the way down to zero.

Through the looking-glass

But why stop at zero? Why not go even further, as the Danish and Swedish central banks have done, and introduce negative interest rates? That was the recent suggestion of the Bank's deputy governor, Paul Tucker.

Negative rates would mean that the High Street banks end up paying the Bank of England to look after their spare cash.

The banks would then pass this cost onto us by charging us interest on our bank accounts and our savings.

This could however cause some technical problems.

For example, banks' computer systems may simply not be set up to start charging interest where previously they paid it. Or they may not have the contractual right to do so.

There may also be a psychological effect. If savers do start getting charged interest, they may simply withdraw their money and use it to buy gold, or just hoard the cash.

However, storing vast amounts of these assets is not so simple.

Banknotes stuffed under mattresses are at risk of theft and decay. As for gold, its price could go down just as easily as it has shot up in recent years.

Option 2: Mad about inflation

What can central bankers do to overturn their straight-laced reputations?

The job of a central bank used to be simple: Inflation was enemy number one.

Anyone who lived through the 1970s and early 1980s - when shop prices in this country were rising 10%-20% a year - will know why. Out-of-control inflation is disorientating, and can hurt your pocket.

More recently, the cost of living has experienced another nasty upward jolt, with inflation peaking at over 5% in 2011 thanks to the weak pound, VAT hikes and rising world food and energy prices.

So it may come as a surprise to learn that many economists now think the way forward is for the Bank of England to engineer more inflation, not less.

Thought experiment

The argument goes that things are very different now than in the 1970s.

Since the Thatcher government's tussle with the unions, workers have much less power to demand wage increases, which means that inflation is less likely to get out of control.

These days, what many workers have instead are huge mortgages. And higher inflation can actually make those mortgages more manageable.

To understand why, do a thought experiment.

Imagine that every price in the country doubled overnight, not just the prices in the shops and restaurants and factories, but also the price of everyone's labour, our wages.

In principle nothing would have changed. You would be earning twice as much, but you would also be paying twice as much.

The only thing that would not change is everyone's debts and savings. In effect, their value would have halved overnight. That is what inflation does, much more gradually, to savings and debts.

Sleight of hand

Inflation, when it is not offset by higher interest rates, makes debts easier to repay. And it creates an incentive for big companies and other savers to go out and spend their cash-piles before they lose value.

In other words - and this is how most economists would view it - raising the inflation rate is a cheeky way of achieving the same outcome as an interest rate cut. It's a bit like having Baldrick run towards your fist, external.

The fear at the back of many economists' minds, not just in the UK, but also in the US and eurozone, is that if they don't do this, they may end up like Japan.

Japan suffered its own debt-fuelled financial crisis in 1990, and ever since then the country has suffered from de-flation - falling prices.

As a result, the value measured in yen of everything produced by the country's economy in 2011 was exactly the same as it was in 1991.

Most countries hope eventually to outgrow their debts - that is what happened with the debts run up by the UK and US to finance World War II. Our economies grew rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s, but our debts did not, making them more and more manageable as time passed.

But, thanks to 20 years of falling prices, Japan has simply failed to do this.

Inflation bad

With all this in mind, the Bank of England's incoming Canadian governor, Mark Carney, has called for a debate about whether to change the Bank's job description.

Currently, the Bank is required to keep inflation as close as possible to 2% per year.

One option on the table is to target "nominal GDP" instead. In plain English, this would mean that if the economy does not grow fast enough, the Bank would be obliged to encourage faster price rises instead.

There are, however, many practical problems with this option, as the BBC's Stephanie Flanders has pointed out.

Other possible targets have also been mooted, but what they all have in common is that they would allow the Bank to pursue faster inflation.

But promising more inflation is not enough, the promise has to be credible. If people and businesses are to be convinced to go out and spend more, they have to truly believe that the Bank will do what it says on its tin.

The problem is that old habits die hard. After the bruising experiences of the 1970s, many central bankers throughout the Western world still fret about losing their straight-laced, inflation-fighting credentials.

This Pavlovian fear is even stronger in Germany, where the hyper-inflation of the 1920s is linked in policymakers' minds to the rise of Hitler.

Crazy promise

In fact, so ingrained is the aversion to inflation, that some economists argue that the credibility of central bankers is the problem.

The outspoken left-wing economist Paul Krugman, external has called for the US Federal Reserve to "credibly promise to be irresponsible" - to say that it will continue stoking inflation even after the US economy has already recovered.

According to Prof Krugman, that is the only way that the central bank could convince everyone that they really ought to go out and start spending their money right now before prices start rising.

Others have gone further, saying the Fed chairman Ben Bernanke should don a Hawaiian shirt and smoke a bong, external, to make the crazy promise more credible.

Across the Pacific, many have blamed Japan's central bankers for being too half-hearted about tackling deflation. In 2000, and again in 2006, the Bank of Japan was all too ready to raise interest rates at the first sign of a return of rising prices.

Japan's newly-elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has sought to tackle this credibility problem by doubling the central bank's inflation target to 2%, and - perhaps more importantly - by trampling all over its independence.

He has certainly convinced the financial markets that Japan will finally break its deflation habit, external.

The central bank's new head, Haruhiko Karuda, has promised to do "everything possible".

But, with interest rates already at zero and the Bank of Japan having already engaged in the biggest quantitative easing effort on the planet, it could be that even with all the will in the world, the task may simply prove impossible.

Option 3: Money for nothing

In a depressed economy, can central banks give money away with impunity?

Both options considered so far are in reality just clever ways of pursuing traditional monetary policy.

In other words, they involve penalising savers and making it cheaper to borrow.

But some argue that traditional monetary policy is what got us into so much trouble in the first place, external.

The argument goes that since the 1980s, inflation and interest rates have fallen steadily across the Western world. Every time our economies got into trouble, central banks came rushing to the rescue by making it cheaper to borrow.

This culminated in a period dubbed the "Great Stability", more than a decade of stable growth and inflation from the early 1990s up until 2007, during which the US Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan was elevated to the status of a demigod.

In reality, the cheap cost of borrowing and the expectation that the monetary authorities would always come to the rescue, (the "Greenspan put", external), simply encouraged everybody to take on far too much debt, especially the banks.

And all that cheap money fuelled financial bubbles, first the emerging markets and dotcom bubbles of the 1990s, then the far more devastating global housing bubble of the noughties.

Now that the debts have got out of hand, perhaps it is a good thing that traditional monetary policy has reached its natural limit.

Easy as one, two, three

There is, however, a more direct monetary solution to our malaise that does not involve creating even more debt. The Bank of England could just give money away.

On the face of it, the policy sounds irresponsible.

But, it has been backed by many economists, including the former City regulator Lord Turner, the Financial Times' resident economist Martin Wolf, external, and - many years ago - by the US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke, external.

The idea was originally proposed by the famous monetary economist Milton Friedman, who in 1969 suggested tongue-in-cheek that the Fed could simply fly around the US dropping bundles of $100 bills.

Of course, it would be crazy to literally hand out billions of dollars in banknotes with no oversight of where it ends up - although the US did try this in Iraq, with predictable results, external.

Indeed, in the UK the Bank of England lacks the authority to give money away. That is the Treasury's prerogative. So the option of "helicopter money" would involve a collaboration between the two.

The actual monetary mechanics are a little hazy, as Stephanie Flanders has explained at length.

But they would work something like this:

The Treasury issues a £100bn-IOU to the Bank

In return, the Bank hands over £100bn in newly-created money to the Treasury

The Treasury spends the money

Note that step 3 is the critical one that differentiates helicopter money from QE, and it requires a Treasury willing to engage in more spending.

In theory, there is no debt created.

So long as you consider the Bank to be part of the government - which, incidentally, official measures of the government's debt do not - then the £100bn-IOU is just money that the government owes itself.

But if you wanted to be totally sure, you could say that the IOU never pays interest and never has to be redeemed.

Hyper-reality

Whether the Bank should do this is a far more vexed question.

Despite its many fans, helicopter money also has plenty of opponents, including the departing Bank of England governor Sir Mervyn King, external.

The policy is also known as currency debasement, and lay behind the many hyper-inflations in history, including those of Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe.

It would certainly give the currency traders in the City, whose job it is to value the pound day after day, something to think about.

When investors lose confidence in a currency, they can lose it very quickly. The pound had one brief scare in late 2008, when its value plummeted to almost one euro.

Even though it has recovered since then, sterling has still lost a quarter of its value since the 2008 crisis, external. It is a tumble twice as big as our humiliating exit from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism on Black Wednesday in 1992 and one of the main reasons why our cost of living has risen so painfully.

But, if the process could be carefully controlled by the Bank, a further weakening of the currency would arguably do us quite a bit of good, by making our exports more price competitive at a time when our biggest export-earner, financial services, is in a long-term post-bubble decline.

But even if helicopter money could be distributed without panicking the markets - for instance, via a strict promise by the Bank of England to keep a lid on inflation - it also begs one other interesting question.

What exactly would the Treasury spend the money on?

Option 4: Concrete action

Road building helped many economies to escape the Depression in the 1930s

The solution proposed by the Depression-era economist John Maynard Keynes was for the government to hire the unemployed in public works schemes.

This puts wages in the hands of people most inclined to go out and spend it, providing extra oomph to the economy.

And those workers could be employed to build useful stuff. Traditionally, this meant things like roads, schools and hospitals.

Here are a few examples of useful things the UK government might consider building today:

What matters is that these are all things that increase the economy's long-term productive capacity. In other words, they should boost both sides of the equation - demand and supply.

Overspending problem

The subject is clearly a hot topic within government. That much is clear from a recent opinion piece by the Business Secretary Vince Cable, external, in which he appeared to express regret for the speed with which the government slashed its infrastructure spending after 2010.

But what about the deficit? Can the government afford to borrow and spend more. And if it does so, will it not scare off investors?

If it were financed by helicopter money, it would not add to the deficit at all.

But let's instead assume the government borrowed the money from the markets, taking advantage of the fact that it can currently borrow at an interest rate below the rate of inflation, external, and that now is a great time to hire construction companies on the cheap.

The chancellor's commitment is to cut the structural deficit within five years.

But infrastructure spending counts as "capital expenditure", and as such is not part of the structural deficit. That is because building useful things creates a tangible new asset that belongs to the government.

The distinction between capital spending and the structural deficit is important.

It is a bit like the difference between your mortgage and your credit card. Generally speaking, you can always repay your mortgage by selling your house. But if your credit card balance is snowballing, then you have a serious overspending problem to deal with.

For the same reason, the financial markets should be reasonably comfortable with lending the government the money it needs to build, say, a new high-speed rail link. The government can always privatise the railway line to repay the debt.

In fact, it is even better than that. A lot of the benefit of new infrastructure is not captured directly by the owner.

That is because the value to the economy of connecting two cities together is far greater than the amount any private company could make from a toll road.

But the government does ultimately see most of the benefit, because a more productive economy is one that produces more tax revenues. So, in the long-run, the new road - if it is genuinely useful - should more than pay for itself.

In fact, as Vince Cable points out, the government may even recoup a large part of the cost right away.

Hiring unemployed construction workers and engineers to build a new line from Euston to Birmingham creates wages and profits on which taxes can be levied. And when those construction workers and engineers go out and spend their wages, that creates even more economic activity and even more tax revenues.

Political will

But George Osborne has done conspicuously little to boost infrastructure spending.

The total increase in capital expenditure and guarantees announced in the Autumn Statement was just £45bn over the next two-and-a-half years, or about 1% of economic output.

Besides his perennial concern about not appearing to increase the government debt burden, the chancellor may see several other limitations with the public works option.

Firstly, infrastructure projects are notoriously expensive on our densely populated island.

The cost of designing and building a new sewerage system or waste incinerator can be made prohibitive by the high price of land, the need to work around existing buildings, roads, electricity cables, pipes, and so forth, and of course the need to respect the rights of residents and landowners.

Moreover, even if the government did decide today to push ahead with, for example, doubling the size of Heathrow, the delays caused by the UK's cumbersome planning process - which the prime minister has promised to streamline somewhat - and the logistics involved mean that little spending would actually happen before the next election.

Vince Cable counters that the very anticipation of this government spending would stimulate more spending by private sector businesses.

But then there are examples of governments throughout the world simply wasting much of the money by building what is politically valuable, not what is economically valuable, as Spain has discovered to its cost in recent years, external.

And it may be reasonable to ask whether the civil service has the capacity to handle a massive increase in the number of complex and expensive infrastructure projects it must handle, given the recent experience of the aborted award of the West Coast Main Line franchise.

Option 5: Off the hook

Past campaigns for a debt jubilee sought to help the world's poorest nations

Perhaps the most direct solution to Western economies' debt problems has been proposed by Australian economist Steve Keen.

Just get rid of the debt.

He has advocated a modern version of the biblical debt jubilee, in which the government eliminates a big portion of everyone's obligations as a one-off measure.

There are many ways in which it could be done.

For example, the Treasury could write a cheque for, say, £10,000 in newly-minted helicopter money to everyone in the country, on the condition that the cheque must be used to pay off existing debts.

Prof Keen says, to ensure fairness and political acceptability, and to give the economy a bit more of a kick-start, every citizen should get a cheque.

The lucky ones without any debts could just go out and spend the money.

Or, if that looked likely to unleash an unmanageable wave of car purchases, perhaps they could be told to put the cheque in their pension fund, or - if they are retired already - to buy an annuity.

Odious

It is worth taking a moment to understand Prof Keen's somewhat unorthodox view, external of the malaise the West currently finds itself in.

He contends that most borrowers currently stuck with unmanageable debts have been the victims of an enormous inadvertent swindle, or Ponzi scheme, carried out by the financial system.

The most obvious example of this is a homebuyer who took on a mortgage to pay, and help drive up, the overinflated price of a house during the property bubble.

When the bubble burst, the price of their house fell back to earth, but their debt did not disappear.

Even if the debts are not cancelled, Prof Keen says much of the debt is not ultimately capable of being repaid, although it may take years before this fact becomes apparent.

But besides the practical aspect, Prof Keen believes there is also a moral case. He thinks that much of the debt is illegitimate - or "odious" - to use the legal term, and ought by rights to be cancelled.

Whether or not you agree with his overall thesis, the idea of using helicopter money to repay debts does provide a way of stimulating the economy, whilst also putting our collective finances on a more sustainable footing.

Apart from the obvious benefit to the citizens receiving this manna from heaven, it would also be a boon to the banks, who would find £10,000 of every personal loan they had extended being repaid.

Defying gravity

There are, however, several objections.

First of all, it is not obvious that the UK has actually experienced an unsustainable housing bubble in the same way that the US, Spain, Ireland and many other economies have. This is a point made by Ben Broadbent of the Bank of England, external.

The UK actually faces a serious housing shortage, and, accordingly, property prices have not collapsed in the last five years in the way they have done in those other countries.

However, the apparent resilience of the UK property market could also be due to the very different approach taken by mortgage lenders to their struggling borrowers compared with, for example, their US peers.

In the US, homes were repossessed and then dumped on the market in their hundreds of thousands. This forced property prices down, external but kept total sales higher than they might otherwise have been, external.

In the UK by contrast, repossessions have been relatively modest, external. Our banks have been keen not to push their many overstretched borrowers over the brink, perhaps for fear of sparking a property market crash that could drag them down with it.

Instead, they have been allowing borrowers to delay their repayments. Up to 8% of homebuyer mortgages and a third of commercial real estate loans were estimated by the Financial Services Authority to be in this situation, known as forbearance, external.

And while these zombie loans remain a dead weight on their books, the banks have cut back their lending to everyone else, including perfectly healthy businesses.

But while forbearance may have succeeded in avoiding a collapse in UK property prices, external - at least in the South East - prices are stuck at levels that are unaffordable for many buyers, particularly first-time buyers. As a result, the total volume of sales has collapsed and barely begun to recover, external.

Short memories?

A second objection to the debt jubilee is that it could be inflationary.

The authorities would certainly run the risk of unleashing a massive and unmanageable surge in spending if they handed out too much debt and wiped out too much in one fell swoop. But this may just be an argument for carrying out the jubilee in small increments.

However, the sheer novelty of a mass debt write-off, let alone helicopter money, might be difficult for the financial markets to digest. So there may well be a risk of triggering a collapse of confidence in sterling.

Another concern is the precedent that the jubilee would set - the so-called moral hazard risk.

If people get it in to their heads that if they run up too much debt, the government will come running to their rescue, what is to stop them running up even more debt in the future?

Is it possible that people might unlearn the lesson of the past five years, that we cannot go on borrowing forever?