Spain's recession worsens in the fourth quarter

- Published

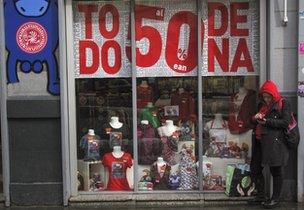

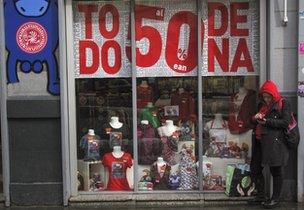

Confidence among eurozone businesses rose in January, but far less so among retailers

The downturn in the Spanish economy worsened in the final three months of 2012, as output fell 1.8% from a year earlier, official data has indicated.

Output shrank 0.7% from the previous quarter, external - the worst performance in Spain since the 2009 global recession.

Spain suffers from uncompetitiveness inside the eurozone, a troubled banking sector, excessive household and company debts, and harsh government austerity.

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy responded by announcing a new stimulus package.

The package is expected to include tax cuts for young entrepreneurs, but is unlikely to reverse the thrust of the government's austerity programme.

Under pressure from European peers, the government is seeking to cut its deficit - its yearly overspending and resulting borrowing need - from 9.4% of economic output in 2011 and 6.3% last year, to 4.5% this year and 2.8% next.

Coming off the drip

Government spending cuts have taken a heavy toll on the Spanish economy - the latest data indicates that the unemployment has reached 26% of the workforce, the highest rate since the country returned to democracy in 1975, with a total of just under six million people unable to find work.

Young people say there are no opportunities to get a job

Spain's economic and financial woes raised widespread fears in the financial community last year that the country may ultimately be unable to repay its debts, and may even have to leave the eurozone.

However, the threat from financial markets to pull the plug on Spain's government and banks, by refusing to relend them the money they need, has lifted since the summer due to intervention by the European Central Bank (ECB).

From the end of 2011, the ECB offered banks in the eurozone's troubled southern economies unprecedented and cheap four-year loans, stemming a crisis of confidence in Europe's banking sector.

The first optional pre-payment date for the loans falls on Wednesday, and several of Spain's biggest banks, including BBVA, Banco Popular and Sabadell, have said they will repay a significant chunk of the loans, signalling that they have garnered enough confidence from other lenders to begin taking themselves off the ECB's emergency drip.

But although eurozone banks are finding it easier to borrow, they are still cutting back on how much they are willing to lend to the rest of the economy, according to the ECB.

The central bank's most recent quarterly Bank Lending Survey, external, released on Wednesday, found that banks in southern Europe, reduced their lending in the last three months of 2012, and expect to do so again during the current quarter.

Banks are responding to demands from regulators to increase their ability to absorb losses on existing loans, and to the general weakness of the eurozone economy, according to Carsten Brzeski, economist at ING.

Confidence among eurozone businesses rose in January, but far less so among retailers

"This illustrates the double credit whammy in the euro zone," he said. "Tightening of credit conditions on supply side and a fall in demand, it's a squeeze on both sides.

"[The] crisis of the real economy is far from being over and these numbers support the ECB's view that growth will only return in the second half of the year."

Ease off?

In July last year, ECB President Mario Draghi announced the central bank would do "whatever it takes" to prevent countries dropping out of the eurozone, and later offered to buy unlimited amounts of the debts of governments such as Spain and Italy, subject to strict conditions that they get their deficits under control.

Although neither government has so far taken up the ECB's offer, the mere knowledge that neither Italy nor Spain faces the immediate prospect of running out of money to pay their bills has restored market confidence in both of them.

On Wednesday, following the release of Spain's disappointing growth data, the government's 10-year implied cost of borrowing nonetheless held steady in markets at about 5.15% - well down from the 7.62% that it peaked at last July.

However, the ECB's interventions have not removed the economic challenge to Spain of regaining wage-competitiveness versus Germany within the eurozone, and for the government to get its overspending under control.

Addressing both of these challenges is widely expected by economists to involve many more months or years of grindingly slow growth or even recession.

Spain's Economy Minister, Luis de Guindos, said in Davos on Friday that he expected the economy to return to positive growth only in the second half of this year.

The success of the ECB in taming the markets has also raised concerns that Madrid may now ease off on the spending cuts and labour market reforms that are still thought to be necessary to restore long-term economic health.

Spain has some support for going slow on austerity from the International Monetary Fund, whose chief economist Olivier Blanchard recently warned that the economic pain caused by government spending cuts across the over-indebted industrialised world since 2009 has proved far worse than expected.

Return of optimism

Meanwhile, survey data released by the European Commission on Wednesday, external indicated that the ECB's actions were beginning to filter through to the broader economy.

Confidence among both businessmen and consumers rose for the third month in a row in January, according to the Commission's latest regular survey, with the upturn in business sentiment stronger than had been expected by many economists.

Its economic sentiment index for the eurozone rose to 89.2 from 87.8 in December, still well below the 100 level that marks the boundary between overall optimism and pessimism.

The rebound in confidence was most marked in Germany, while Spain, France and Italy all lagged.

This was also reflected in the ECB's Bank Lending Survey, which showed that of all the major eurozone economies, only Germany's saw a notable increase in lending, driven largely by new mortgages.

However, businessmen across the eurozone operating in the retail sector did not show greater confidence, according to the survey, chiming with separate survey data from research firm Markit, external that indicated retail sales across the single currency area fell for the fifteenth month in a row in January.

"[It] reminds us that consumers remain under pressure from high unemployment, squeezed incomes and uncertainty about the financial outlook, and that any substantial upturn in domestic demand, especially from households, is unlikely to occur any time soon and is therefore unlikely to help drive economic recovery," said Markit chief economist Chris Williamson.