Mark Carney: A stranger in a foreign land?

- Published

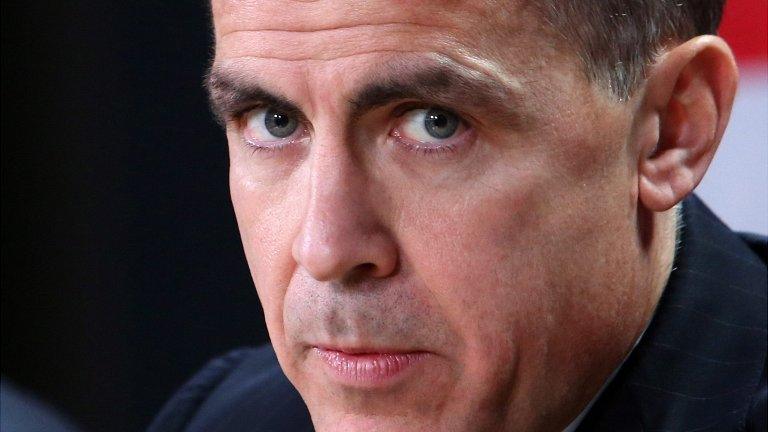

As an unknown quantity in the UK, Mr Carney will be under intense scrutiny

All eyes in the City will be firmly fixed on Bank of England governor Mark Carney in the coming weeks.

And for many reasons - the parlous state of the UK economy and the Bank's new and vastly expanded role within it, not to mention the new boss's reputation as one of the most charismatic central bankers around.

Perhaps most important of all, however, he is the first foreigner to run the Bank in its more than 300-year history. In other words, he is something of an outsider, and will be scrutinised all the more for it.

So what can we, and he, expect from his first few weeks in charge?

A lot to live up to

Mr Carney will have to convince his new colleagues, the City and the media he is up the job. And here, his reputation could be as much of a hindrance as a help. Being described by Chancellor George Osborne as the "outstanding central banker of his generation" is quite some introduction. No pressure there then.

His appointment was almost universally praised in the media, which saw it as bold and imaginative. Whether it was viewed as such within the Bank, given that deputy governor Paul Tucker was odds-on favourite for the job, is another matter. Mr Tucker has since announced he will be leaving the Bank.

What is certain, though, is that expectations are almost impossibly high.

Settling in

The new boss will have to settle in to what appears, at least from the outside, to be a rather stuffy, old-school institution.

David Blanchflower, ex-member of the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) and Professor of Economics at Dartmouth College in the US, describes it as "stodgy".

"There is an unwritten rule that if you want to take your jacket off [at meetings], you have to wait for the governor. The Bank is very stuffy. The Federal Reserve is not like that, and Mark Carney is not like that."

Whether he adapts to the Bank's culture or it adapts to him will be important. No doubt a balance will be struck, but Prof Blanchflower is in no doubt the new boss will have to bring in his own people and "start cracking heads".

This, he argues, is the backdrop to the appointment of the Bank's first chief operating officer last month, Charlotte Hogg - the first senior female appointment in the Bank's history.

Honeymoon period

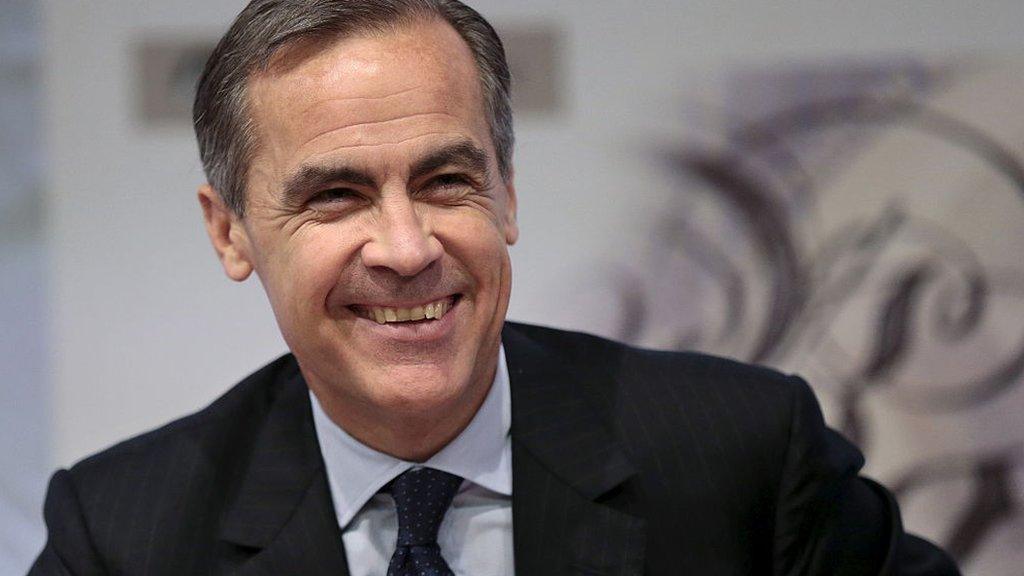

In his first week in the job, Mr Carney will chair the MPC's monthly meeting. It is here that the tone will be set for the rest of his five-year tenure, and the notes of the meeting published two weeks later will give an important insight in to how receptive the rest of the committee is to his ideas.

Vicky Redwood at Capital Economics believes now is the time for him to push through change, when the feel-good factor may encourage a renewed spirit of co-operation.

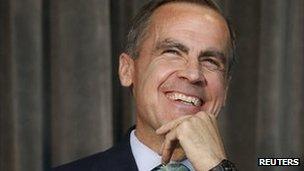

Mr Carney has a reputation as a smooth operator and one of the most charismatic central bankers

For there are major divisions within the MPC. Mr Carney's predecessor Sir Mervyn King was outvoted for five straight months when the committee voted six-three against expanding the Bank's policy of quantitative easing (QE), essentially pumping money into the economy to help stimulate growth.

And it's not just the MPC Mr Carney needs to keep onside. The press is a fickle beast and questions have already been raised about his £480,000 salary, while comments from his wife about the difficulty of finding acceptable accommodation for their £250,000 a year housing allowance could come back to bite.

Questions are also being raised about the current state of the Canadian economy, hitherto held up as an example of how to withstand a global financial crisis.

As Ms Redwood says: "Mr Carney may be getting out at the right time."

Down to business

Whether Mr Carney has arrived in the UK at the right time depends on your view of the economy.

"In a way, he has been given something of a poisoned chalice," says Prof Blanchflower. "The economy is not in recovery, it is not healing, it is not [even] out of intensive care."

Ms Redwood sees things differently, arguing there has been a tentative recovery, but what is certain is that more needs to be done to turn the economy round. And this is what Mr Carney has been brought in to do.

There are a number of obvious places he can start. First is to expand QE and inject more money into the economy. Mr Carney may be able to persuade his colleagues to do so if the Bank widens the remit of QE beyond buying gilts, says Ms Redwood. Buying up private sector assets to the tune of £10bn has already been agreed in principle, for example.

Mr Carney may follow Fed Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke in giving forward policy guidance

Mr Carney could also cut interest rates further, and after the Bank's deputy governor Charlie Bean raised the subject recently, this option is "back on table", says Prof Blanchflower. Reducing the rate paid on bank reserves, as a way of encouraging them to lend more, is another possibility.

Boosting bank lending will also be a priority. This is likely to be a popular commitment among the MPC given its enthusiasm for the government's Funding for Lending Scheme, which is specifically designed to lift bank lending. Mr Carney could, for example, relax banks' liquidity restraints.

One thing he is likely to introduce is some form of so-called forward guidance, essentially giving an indication of future policy. He has all but said he intends to be more open in this respect.

You just have to look at markets' fearful reaction to Federal Reserve head Ben Bernanke's recent hints that the US's own QE programme may begin winding down at the end of this year to see the importance of managing the expectations of investors.

Reassurances that interest rates will remain low for a set period would, for example, allay many investors' fears. Such a commitment could even be pegged to the rate of unemployment - until it falls below a certain level, rates will remain on hold.

Of course it's one thing making promises and quite another convincing others to believe them, let alone making them happen.

What is certain, however, is that double dip or no double dip, the economy is struggling to show any signs of meaningful recovery and Mr Carney has a great opportunity to push through policies to help stimulate growth. Just as importantly, markets expect him to do so.

- Published31 October 2016

- Published28 June 2013

- Published26 November 2012