When will the Federal Reserve get back to normal?

- Published

For the past five years, officials at the Fed have been operating under abnormal circumstances

Read any article about the US Federal Reserve in the past year and the same phrase appears over and over again: "extraordinary stimulus measures".

While that is partially due to a lack of imagination on the part of me and my fellow business journalists, the reality is that the extraordinary has become, much to the Fed's dismay, ordinary.

Since 2012, the US central bank has engaged in an $85bn (£52bn) a month bond-buying programme in order to lower interest rates and encourage spending.

This effort - known as "quantitative easing" (QE), a phrase for which I'd also like to apologise on behalf of journalists and economists - was meant to prop up a weak US economy at a time of sluggish job growth and depressed spending.

It followed two earlier efforts - QE1, in 2008, and QE2, in 2010, for the jargon obsessed - to boost US growth.

While some have doubted the efficacy of QE to spur economic activity, no one questions the size.

In total, these efforts have expanded the Fed's balance sheet, external (essentially, the amount of new money the central bank has printed and now holds as debt) to close to $4 trillion - more than the economic output of Germany, the world's fourth biggest economy.

Now, the question is how the Fed will begin its rebalancing act.

A tightrope walk

To take a step back, remember the "ordinary measures" of central banks around the world are to raise and lower short-term interest rates.

As part of its "extraordinary measures" the Fed has printed close to $4 trillion

This is something the Fed has been unable to do since 2008, when it lowered the main federal funds rate to between zero and 0.25% (in economist speak, it is when the Fed hit the "zero lower bound").

Remember, the Fed funds rate is the benchmark rate from which all other rates - like mortgage rates and car loans and even global lending rates - are derived. Since the Fed hasn't been able to lower short-term interest rates, it has resorted to bond buying to lower long-term rates.

The Fed took its first step on 18 December in its quest to re-normalise policy by engaging in a move known as a "taper". (If you're looking around for a Fed to English dictionary, I'm sorry to say it's still at the printers.)

Tapering is slowing down the $85bn a month bond-buying programme. In this case, the Fed said it would only buy $75bn worth of bonds each month going forward.

But this doesn't mean this will be the case for long.

"Note that [Chairman Ben Bernanke] has never used 'taper' - the word taper implies that once you start you go on a straight line down," says Fed "translator" Randall Kroszner, a former governor of the central bank who served from 2006 to 2009.

"I don't think that's how the Fed is thinking about it. I think they'll have a step down and then see what the impact is on markets and the economy and then decide what the next steps will be."

Mr Kroszner says that subsequently working out when to completely remove all stimulus efforts - not when to start the process - is perhaps the most difficult decision facing the Fed.

"One of the key questions will be the timing of the exit, making sure that the economy is on a robust and sustainable recovery path - that's very difficult to predict, and it's really where the art rather than the science of central banking comes in," he says.

Getting back to normal

But even when QE3 is done and dusted, it will take some time for the Fed to offload some of the trillions of dollars on its balance sheet.

The assumption is that instead of trying to sell the various bonds it has purchased over the years, the Fed will instead let them "mature" - that is, become due.

But this will take some time: one forecast , externalby economists at the bank found that it could return to normal sometime between mid-2019 and mid-2021.

There is also the matter of the other "extraordinary measure" being used: forward guidance.

"Forward guidance" refers to the Fed's effort to manage expectations by communicating expectations about interest rates and the economy in press conferences and written statements.

It is meant to help investors, and markets as a whole, better plan for the Fed's policies.

"Communications have become just as crucial a tool of monetary policy as any other traditional strategy," says Mr Kroszner.

But again, it is a tool that is not as effective as simply lowering interest rates, and many observers assume the Fed will rely on it less as a tool once monetary policy gets back to normal.

'Recipe for turbulence'

The Fed has said it will start raising interest rates sometime in 2015, external, once the unemployment rate falls below 6.5% and inflation remains within the bank's 2% target.

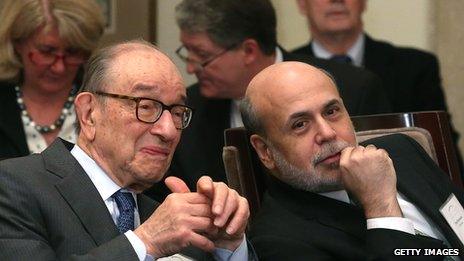

Alan Greenspan (l) & Ben Bernanke benefited from taking over during "normal" times

But even once the Fed can return to its preferred tool, there are some who doubt that things will ever return to their pre-recession status.

"We're not going to go back to the old world - it's just not going to happen," argues former Fed economist Joseph Gagnon.

In the old world, the Federal Reserve targeted a federal funds rate of 4% - or a "real" rate of 2%, when inflation, ideally at 2%, is taken into account.

But Mr Gagnon and others, including former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, external, argue that these targets might no longer be relevant.

As the US population ages, the labour force participation rate declines, and trade deficits remain high, it could be that expectations need to be recalibrated. The "natural rate" of interest might be lower, particularly as the working age population in the US is only expected to grow 0.2% between 2015 and 2025.

Some economists, like Princeton's Alan Blinder, have argued, external that due to these factors, it might be prudent for the Fed to never abandon, to return to the theme, its "extraordinary measures".

Whatever happens, Mr Gagnon says that the next few years will be "a recipe for turbulence".

- Published22 October 2013