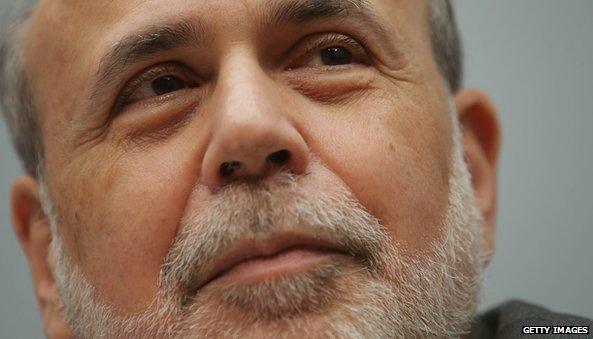

So long, Ben Bernanke: a personal goodbye

- Published

So long, Ben: Mr Bernanke steps down after eight years at the helm of the Federal Reserve

We all have moments from our youth that we'd like to forget - braces, unfortunate haircuts, an obsession with certain boy bands. Here's my little secret: my teenage crush was Ben Bernanke.

As his tumultuous eight-year term as head of the US Federal Reserve comes to a close, I thought it time to finally air this fact.

How it happened: I was part of a competition, aimed at secondary school students, in which four of my classmates and I pretended to be members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) during a policy meeting, arguing over interest rates.

Did I mention I was a particularly cool teenager?

Kim Gittleson (centre) with her teammates and coach at the Fed

But I wasn't the only teenager ready to tackle the challenges of macroeconomics back in 2004.

Hundreds of eager students across the US were vying for the championship crown in the Fed Challenge programme.

But my friends at Rumson Fair-Haven Regional High School and I were driven.

We eventually found ourselves amongst the elite group of four teams of five, competing in the final round in Washington, DC.

In the hallowed chambers of the actual FOMC meeting room - a gigantic place with cream walls and oil portraits - we gave a 15-minute presentation, discussing the issues we thought the adults usually seated around that polished table fretted over.

It was then that it happened.

Across the table were three judges. One was a bearded member of the board of governors, particularly worried that we had not taken the prospect of rising inflation seriously enough.

Cue the swelling music. And I wasn't just hearing the chimes of victory (because yes, of course, we won).

What struck me, even then, was the sense that this was a man who didn't want to tell me what to think, but rather to make sure I understood.

I would later find out that was deliberate.

Fed Challenge students played at being the adults who usually sat in these chairs

"When I was an educator, I quickly came to understand that students are most motivated to learn when they can see the connection of the lesson to their own lives," said Mr Bernanke in a recent speech, external marking 100 years of the Fed.

He added that has been a challenge because "the Fed and its activities, and economics in general, can seem remote from daily concerns".

Even over-ambitious school students like me, lured by the promise of victory and a small scholarship towards university, would often find the words of his predecessor, Alan Greenspan, more than a little opaque.

There's a reason that the journalists who covered the Greenspan era coined the term "fedspeak".

When Mr Bernanke took over as the head of the Fed in 2006, he wanted to change all that - he wanted to do the unthinkable: make Americans care about central banking.

.jpg)

Mr Bernanke's predecessor Alan Greenspan was known for his opaque utterances

"Increasing the Fed's transparency, openness, and accountability has been one of my top priorities as chairman," Mr Bernanke said.

"A more open Fed, in my view, is both a more effective and more democratically legitimate institution," he explained in that same speech.

It was, and continues to be, a daunting task.

According to a recent survey, external, 61% of Americans were unable to pass a basic test of financial literacy that included questions on interest rates, a key part of the Fed's toolkit.

And the financial crisis, which hit two years into his term in 2008, made communication an even more difficult - but also more crucial - goal.

So, Mr Bernanke added press conferences to discuss the Fed's decisions - not only on interest rates but a host of other strange and unusual measures such as the policy of "quantitative easing" and forward guidance.

He attempted to build consensus within the Fed about a proper communications strategy.

"In response to a financial crisis and a deep recession, the Fed's monetary policy communications have proved far more important and have evolved in different ways than I would have envisioned eight years ago," he has said, external.

It's an evolution that continues, and that his successor, Janet Yellen, has said she is committed to continuing into the foreseeable future.

Exit stage left: Ben Bernanke leaves his last press conference as chair in December

Returning to the subject of young love, my relationship with Mr Bernanke didn't end in secondary school.

Four years later, Mr Bernanke arrived as the speaker at my university graduation.

He opened his remarks by noting, external that, unlike his predecessors at the podium, who were normally tapped to give humorous speeches, "central bankers don't do satire as a rule, so I am going to have to strive for 'kind of interesting'".

That's when my crush turned into something closer to inspiration.

Central banking is hard.

It's boring, opaque, and discussed in a jargon that's unfriendly to all but the most dedicated observers - something I realised as a teenager struggling to decipher economic data in preparation for the competition.

But learn how to decode and interpret that chain of acronyms - CPI, PPI, PCE - and it can seem like a revelation, or at least something more than "kind of interesting".

And now, deciphering is what I do - or attempt to do - everyday.

So goodbye, Ben. The crush may have faded but the lesson lives on.

- Published30 January 2014

- Published3 February 2014

- Published18 December 2013