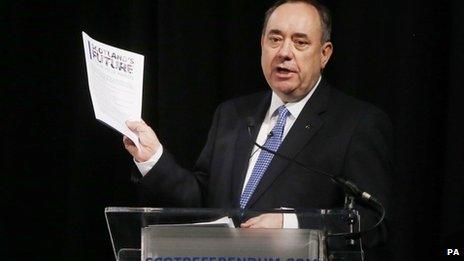

Has the Treasury killed Salmond’s sterling-zone?

- Published

- comments

The instinct of the Scottish National Party may well be to dismiss the head of the Treasury's unambiguous advice to the Chancellor that he should not enter into currency union with an independent Scotland as the public-school and Oxford establishment closing ranks to save the union.

But the letter from Sir Nick Macpherson, external (Eton and Balliol) to George Osborne (St Paul's and Magdalen) is a significant constitutional event.

It is unusual for the permanent secretary to the Treasury to write a public letter on any issue at all, let alone one as momentous as whether institutional arrangements should be put in place so that an autonomous Scotland could have an influence on monetary and financial-regulation policy while continuing to use the pound.

The relevant issue for Mr Salmond is only to a limited extent whether Macpherson and the Treasury are right or wrong that monetary union with an autonomous Scotland would be contrary to the interests of a still-united England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

To remind you what you already know, his strong conviction is that Macpherson and the Treasury are misguided.

But the problem he has is a different one: can he hope to persuade Scots that a Westminster government would ever negotiate currency union with him, now that the official and supposedly impartial civil service has made its view unambiguously clear that negotiating a formally agreed sterling-zone would be a serious error?

In other words, Macpherson has underwritten not only Osborne's opposition to currency union, but that of Labour's Ed Balls (Nottingham High and Keble) and the LibDem's Danny Alexander (Lochaber High - as it happens, a state school - and St Anne's).

Capital flight danger

Which implies not that a separate Scotland could not use the pound. But that it would have to do so in a wholly informal way, with no control over interest rates or regulation of banks or even the supply of adequate quantities of bank notes.

In those circumstances, it would have to grin and bear interest rates and an exchange rate that suited the rest of the UK, but might well be inappropriate to Scotland as a new independent oil-based economy.

So why is Macpherson and the Treasury - which has published a detailed analysis of the costs and benefits of monetary union - so clear that a monetary federation with Scotland would be bad?

Well they make three points.

First that the Scottish National Party has failed to make a forever commitment to keep the pound. It has kept open the option of at some point creating its own currency or joining the euro. But this magnifies the danger of capital flight from Scotland, of a life endangering sort for its banks, any time there were rumours of Scotland dumping sterling (as happened to Greece and Spain, for example, at the height of the eurozone's recent crisis).

That flows through to Macpherson's second point: the Scottish economy and the resources of Scottish taxpayers would be too small to be able to bail out Scotland's giant banks - RBS and Lloyds/HBOS - in a crisis, so the solvency risks attached to these banks would remain with the Westminster government.

Also Macpherson argues that in general, in a currency union, the rest of the UK would perpetually be on the hook to bail out Scotland, and that this would be an unreciprocated or asymmetrical risk - in that, in his view, it would be "inconceivable that a small economy [Scotland] could bail out an economy [England, Wales and Northern Ireland] nearly ten times its size".

'Hogwash?'

Finally he says that the tax and spending or fiscal policies of Scotland and the rest of the UK were likely to become "increasingly misaligned", unless Scotland were put in a fiscal straight jacket that caused growing demands in Scotland for withdrawal from the currency union - which in turn would risk the capital flight and run on the banks that could do such serious economic damage to both parts of the sterling zone.

Now Salmond will say this is all hogwash.

He will argue that the finances and economy of Scotland have a long history of being in step with that of the rest of the UK. And given the importance of Scottish trade to English companies, it would be bonkers to introduce friction and additional costs into the trading relationship by adopting two currencies.

Salmond may be right.

But it is perfectly clear that every important decision-maker in Westminster, political and non-political, disagrees with him. Which means this is less about the fundamental economics than about what an independent Scotland could ever expect to negotiate.

And Salmond's threat of retaliation - that Scotland won't assume any of the UK's public-sector debts if there is no monetary union - is also dismissed by Macpherson.

He makes the unoriginal point that a Scotland seen to be reneging on its fair share of the UK's debts would probably be punished by investors when it tried to borrow as a separate sovereign state, that they would extract a punitive interest rate from Edinburgh.

'Increased hardship'

For what it's worth, that is what investors tell me, though it is not provable beyond doubt.

But Macpherson also tries to get his revenge in early - namely that a Scotland that didn't take the debts could not count on UK support when negotiating with the "international community" (on issues like the terms of Scotland's membership of the EU, for example).

And even if a reborn independent Scotland were to walk away from all the UK's debts, Macpherson says that "it is more than likely that the increase in funding costs, which the continuing UK would face, would be smaller than that which would result from an ill thought out currency union with Scotland".

Or to put it another way, he argues that England, Wales and Northern Ireland would be rational to risk a degree of increased hardship - more expensive borrowing for the Westminster government - than take on what he sees as the potentially more costly risk of marrying currencies with a Scotland striving for cultural and economic self-determination.