Bankers' bonuses: Shareholders wary of making allowances

- Published

Bonuses are down but pay is accelerating for bankers in the fast lane

Bankers' bonuses are not what they were.

Don't get me wrong. They haven't shrunk in any way. Far from it.

But nowadays they are called "allowances", and as such slip neatly out of reach of the Capital Requirements Directive, external (CRD) - the new rules from Brussels on bonus capping.

They may get round the rules, but on Wednesday they had problems getting round Barclays shareholders at the bank's annual general meeting.

Standard Life Investments, which holds 1.9% of Barclays shares, said it would vote against its remuneration report, saying it damaged the banks' reputation.

It was not alone. The report was passed, but some 24% of votes cast did not support it.

Protesters at Barclay's AGM tell senior executives what to do with their pay

Institutional shareholders rarely behave this way. Three years ago there were signs of a "shareholder spring" - a revolt by shareholders against overpaid executives.

That seemed to die away - until now.

Not just CEOs

After the ebbing of the financial crisis, bankers' salaries, allowances and bonuses are all firmly on the way back up.

Take, for example, Stuart Gulliver, chief executive of HSBC. He will receive allowances worth £32,000 a week during this year - on top of his £1.2m salary.

It comes in the form of shares which can be sold at various points over the next five years. In addition, he receives a bonus, also paid in shares, taking his total pay to a minimum of £4.2m.

It is not just chief executives who are benefitting. Some 239 of HSBC's bankers received more than £1m last year. Barclays has said it will increase its staff bonus pool by 10% to £2.38bn - despite profits shrinking 30%.

Allowances

Much of this comes in the form of "fixed-pay allowances".

This is a system that is at work across the entire UK investment banking sector and is specifically designed to get round new rules brought in by the CRD.

Allowances can be reviewed, reduced or withdrawn, and differ hardly at all from bonuses.

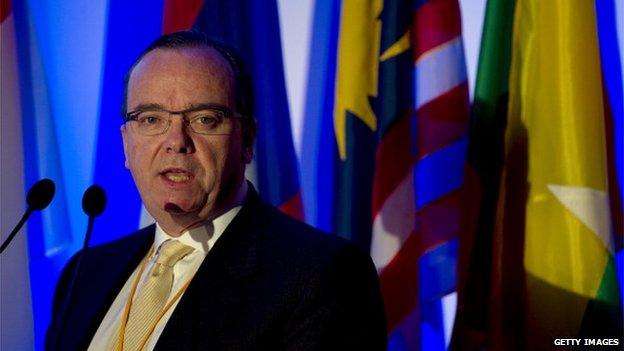

Antony Jenkins: shareholders are taking issue over Barclays pay

The architects of the CRD are furious. One of them, Philippe Lamberts, the Belgian Green MEP has called for the UK to be sued by the European Commission for failing to implement EU law.

He accused the government of having no interest in halting "absurd remuneration packages".

But the rules do not impose a cap on bankers' pay. They do limit bankers' variable pay - bonuses.

Banks can pay out up to 100% of a salary in a bonus at their own discretion. Anything beyond, up to 200%, has to get shareholder approval. Bonuses of more than 200% are banned.

Fixed salaries

Karen Mortenson, associate at the law firm Howard Kennedy FSI's employment team, says: "If the intention has been to cap bankers' pay, it hasn't worked. I really am not convinced there has been a change and overall rates of pay are going up.

"If the intention was to discourage short-termism and risk taking, it seems unnecessary as there are already clawback provisions and deferral mechanisms in place."

The UK is challenging the bonus cap in the European Court of Justice. It believes the rules are skewed against the UK - as indeed they are. The UK has 2,108 investment bankers making more than one million euros a year., external France has the next highest number - just 117.

The directive has had other effects. As bonuses have been cut fixed salaries have risen to make up the difference. That has reduced the flexibility of banks in terms of costs.

But John Terry, partner at PWC's rewards team, says: "The number of individuals that receive these sums is actually fairly small in relation to the population of any major bank. In absolute terms it doesn't add up to much."

However much the rising pay of bankers stokes up the public ire, there is a much more commercial reason to be upset about compensation levels - profitability.

Pay-to-profit ratio

Most banks have been trying to reduce the ratio between employee pay and bank profits. At Barclays, chief executive Antony Jenkins said he wanted that to be in the "mid-30s", that is salary costs taking up 30-40% of profits. Instead it has gone up this last year to over 43%.

HSBC's Stuart Gulliver - allowances of £32,000 a week

Mr Terry says: "The overall share of profits that has gone to compensation has gone down for UK banks but not sufficiently to make up for the decline in the return on equity - the cost of capital.

"Since the financial crisis, the banks have successfully removed themselves from their riskier businesses, but it was the riskier businesses that were so profitable.

"So profitability has fallen and not recovered, and any reduction in the absolute levels of compensation has not matched that fall."

And the institutional shareholders are getting restless. Since October last year UK government reforms, external have given them a binding vote on a resolution to approve a company's remuneration policy. In the past their votes were considered merely advisory.

Shareholder power

Now they have the power to vote down higher pay, if they feel the profitability of their investments is being damaged by excessive salary bills, they may well start exercising that power as they did at the Barclays AGM.

Meanwhile, in the background there is the constant demand from regulators to increase their levels of capital.

In fact the very directive that brought in the caps on bonuses, the CRD, demands higher levels of capital to act as a buffer in times of crisis.

So banks are caught in a triple squeeze of lowering profitability, new rules to increase the amount (and therefore cost) of capital and the perceived need to award higher salaries for the "talent" that brings in the profits.

If profits don't recover sufficiently and if shareholders become more militant, it may, in time, be the fatter pay packets that get sacrificed.

- Published24 April 2014

- Published13 March 2014

- Published5 March 2014

- Published25 September 2013