China's property market: deflating or worse?

- Published

Latest figures show a continued slowdown in credit in China. Aggregate financing, which captures allegedly both official and unofficial lending, fell to 1.55 trillion RMB (£148bn or $249bn) last month from just over 2 trillion RMB in March. It's pushing down property prices as intended, but could it also burst a bubble?

Strolling through the streets of Shanghai, I regularly lose my way. Landmarks, such as a corner store that were there a few months ago, would seemingly disappear, with a behemoth building in its place. Such has been the pace of construction in the mere decade since housing was privatised in China. In that short span of time, house prices have doubled across the nation with prices rising even faster in major cities.

In one respect, it's not a surprise. One of the features of liberalising a market is that prices shoot up. It's what happened in other economies transitioning from central planning. Under the plan, there are always shortages since planners can never quite get the quantity of shoes or indeed flats right. So, once the market is liberalised, there's inflation.

And that's what happened in China. It was only in 2001 when the real estate market was fully launched. Until then, housing was allocated by a person's state-run employer, known as a work unit or danwei. It was part of the "iron rice bowl" where a worker had a job for life, lived in allocated housing, and depended on the state-owned firm for their pension and pretty much everything else.

But, as state-owned firms were effectively privatised in the mid 1990s, housing was also freed from state control.

In 1998, the Chinese government allowed workers to purchase their allocated housing at preferential prices to privatise housing. As the market took off, so did prices. This is also because there are few investment avenues in China.

Returns on savings were poor, and the state-dominated banking system offered few options. Plus, moving money overseas is also not an option for ordinary Chinese as the state imposes capital controls. Unsurprisingly, buying property is popular.

Burst bubble?

For instance, my friend bought her flat under preferential terms from her former state-owned enterprise employer. Since then, the property market has more than doubled in value in Beijing. So, she and her family bought another two flats as investments.

This demand fuels supply. It's particularly the case when cash is plentiful. And it was after the 2008 global financial crisis.

The Chinese government boosted growth by supporting the expansion of credit. A lot of it went into property. As they have begun to rein back credit, it's affecting the property market.

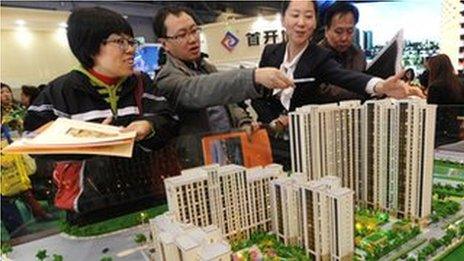

Prices in the 70 major cities tracked by the government continue to rise, but other signs are that the property market is deflating - or worse.

Nomura estimates that prices have fallen in the smaller cities even while big tier 1 cities like Shanghai continue to see price rises. It's why they and some other analysts think that the property bubble has burst.

Also, new building construction fell 25% in the first quarter of the year. Since property accounts for a staggering 16% of GDP, it was one of the contributors to economic growth slowing to 7.4%.

Rising concerns

Plus, land sales in 20 major cities have dropped 5% from a year earlier. That is adding pressure to local governments which derive an eye-watering 61% of revenues from selling land. Without that revenue, they would be tempted to turn to banks and borrow via off-balance sheet vehicles. That's a problem as the opacity of local government debt is a recurring concern.

For ordinary people, house prices coming down isn't disastrous if they can afford the mortgage payments. Unlike in the US or UK, buyers in China typically pay a 30% or higher deposit; it's even been raised to 70% in Shanghai. It is even more restrictive if they are buying a second or even third property. So, even if prices fall by double digits, most households won't be plunged into negative equity.

The problem is that commercial developers tend to be more leveraged. It's their share of the property market that raises concerns. And as China increases its urbanisation - currently just above 50%, which is below that of other major economies - more housing will be needed and developers will want to build.

The best case for China is that property prices moderate. The worst case is that loans are not repaid which drags down the banks. And we in the West know all too well how that ends.