South Sudan economy 'in intensive care' as famine looms

- Published

A child plays on an anti-aircraft gun in South Sudan's oil-rich Unity State as war and famine stalk the land

At night, the glow from the lights of the oil installations in Paloich cuts through many miles of undeveloped South Sudanese countryside.

During the day, the gleaming pipes and hard edges of modern technology stand in stark contrast to the simple huts of the nearby villages.

Oil is the new nation's greatest source of income. But in the three years since South Sudan declared its independence in July 2011, the oil wealth has not brought much development.

Now the oilfields at Paloich and elsewhere are threatened by the civil war that broke out in December 2013, and which is damaging all aspects of life in South Sudan, including the economy.

The fighting between South Sudan government troops and rebels has all but stopped production in Unity State, one of the country's two oil areas.

The rebels have said they are targeting the other area, in Upper Nile state, home to Paloich and other oilfields.

'Precarious'

Overall, oil production is now less than half of the 350,000 barrels per day the country was churning out at the time of independence.

"This is not enough for South Sudan," economist Peter Biar Ajak says. "The financial situation is quite precarious."

Predictions that South Sudan's economy would grow by 35% in 2014 have proved to be tragically wide of the mark.

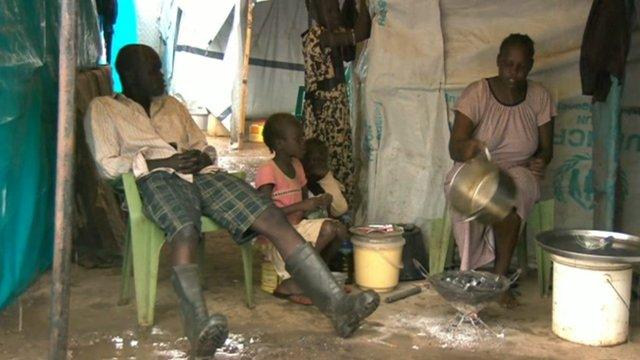

Famine is threatening to add to South Sudan's many economic problems

The fighting has displaced more than a million people, and as farming has been disrupted there are fears the country could slide into famine.

Even in the capital Juba, there are consequences.

"People are not earning money from what they're doing and the prices of everything have increased," says Mike Ismallah, who works at the Konyo Konyo market in the capital, Juba.

With the war rumbling on, no-one is focusing on development or growth now.

Hardship

For many in South Sudan, though, that assessment also holds true for the period before the civil war began.

Independence, which came after decades of conflict with Khartoum, was expected to bring the dividends of peace to the beleaguered South Sudanese.

The years of war, coupled with an even longer period of neglect, meant the vast majority of the population was living in hardship.

South Sudan's president Salva Kiir is at war with rebels backed by former politicians

As its flag was raised for the first time, South Sudan was one of the least developed places on earth.

The late rebel leader John Garang had talked of "taking the towns to the people", bringing representation, development and services to the rural areas where most people live.

The oil billions should have achieved this vision.

Austerity measures

Yet even before conflict broke out in Juba, there was growing dissatisfaction with the pace of change.

As part of a row with Sudan, the South Sudanese leaders took the extraordinary decision, in January 2012, to shut down their own oil production.

The new country needs to export its oil through Sudan's pipelines, refineries and export terminal, but there was no agreement on how much this would cost.

When Khartoum began confiscating South Sudan's oil, the new country's leaders simply stopped the flow from their oilfields.

For more than a year, until a deal was reached with Sudan, the South Sudanese had to live with stringent austerity measures.

All development was put on hold. Salaries came late. Poverty rates grew.

While the South Sudanese celebrate independence, there is little cheer in the economy

A $10bn (£5.8bn; 7.3bn euros) road-building programme, vital for boosting the economy and getting goods to market, was set aside.

A leaked World Bank briefing note warned that the shutdown would probably cause a collapse in the country's overall wealth.

The note also warned of a massive devaluation of the South Sudanese Pound (SSP); an exponential rise in inflation; and a depletion of South Sudan's reserves.

In the end, the fledgling country did survive the shutdown - but it came at a cost.

"The government used some of its reserves, but also borrowed at very expensive commercial terms," says former minister Lual Deng.

According to some reports, almost half of the 2013-14 budget was used to pay back loans.

James Copnall reports on South Sudan's fragile economy

Corruption

The shutdown was not the only problem for the economy - corruption is widespread.

President Salva Kiir famously wrote a letter to 75 current and former officials, accusing them of stealing $4bn.

Most of the rest of the government's money is spent on salaries, particularly for the military.

South Sudanese also complain that the country's resources have not been equally shared.

Any money left after the austerity measures has been concentrated in the national capital, and to a lesser extent the capitals of the 10 states.

.jpg)

South Sudan is blessed with fertile lands yet these bananas are imported from Uganda

Rural development has been close to non-existent.

South Sudan also suffered when Sudan stopped any trade with the new country, driving prices in the border states up.

To complete a gloomy picture, South Sudan's oil is expected to run out in the next few years.

But the country is blessed with abundant fertile land, so the plan is to diversify away from oil towards agriculture.

This will need substantial investment, not just in new technologies and training, but also on physical infrastructure.

At the moment, the roads are so bad that a surplus in one area cannot be taken to market in another, or exported for profit.

However, this much-needed diversification cannot take place while all energy and money is concentrated on the (civil) war effort, and while farmers are fleeing conflict.

Lual Deng's verdict is gloomy: South Sudan's economy is "in intensive care".

- Published9 July 2014

- Published6 August 2018