Qatar 2022: Construction firms accused amid building boom

- Published

Sue Lloyd-Roberts reports from Qatar

The 2022 Qatar World Cup is all about money.

Claims that millions of dollars were paid in bribes to secure the world's biggest football tournament for Qatar refuse to go away.

Qatar is spending more than £200bn ($312bn) on a building bonanza ahead of the tournament.

Everyone seems to be getting rich, except those at the bottom of the human supply chain, the migrant worker.

So what is the responsibility of the international companies awarded massive contracts in Qatar?

We have uncovered worrying testimony about pay, housing conditions and safety standards from foreign workers.

They include some employed by subcontractors working for one of Britain's biggest construction firms, Carillion, based in Wolverhampton.

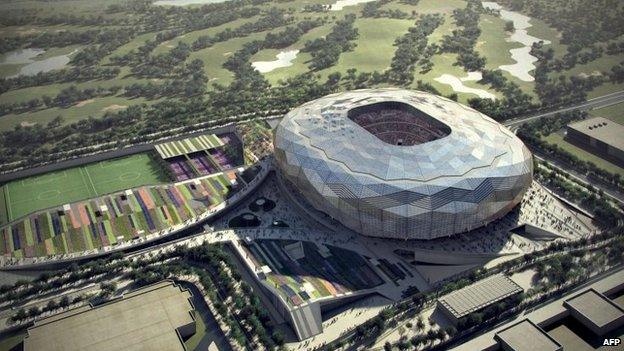

At least eight stadiums are to be built and others will be refurbished for the World Cup.

We were refused permission to film construction at a stadium, so I booked a hotel room to get a look at what is said to be the largest construction site in the world - Msheireb.

It is in the centre of Doha, where there will be shopping malls, apartment blocks and rail links to the stadiums.

At 5am, horns blare and brakes screech as the buses with the day shift arrive.

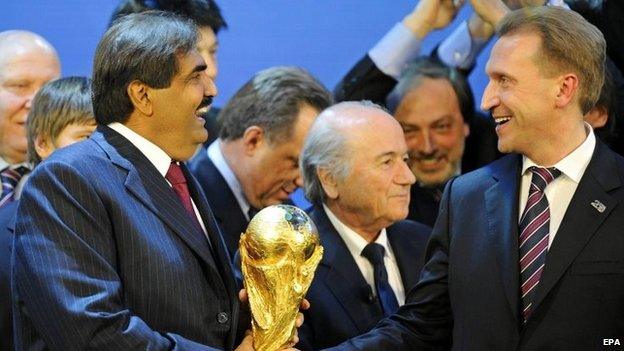

Qatar and Russia were announced as World Cup hosts for 2022 and 2018 four years ago

The shift change is organised with military precision as one gang of workers put aside their tools and climb down the ladders.

Those on the day shift leave the buses in orderly lines, climb up to the recently abandoned positions and start work.

It looks impressive but when I get to talk to the workers, a different picture emerges.

Imran, a 32-year-old from Bangladesh, says he deeply regrets coming to Qatar.

A recruitment agent promised him 1,500 Qatari riyal (£263) a month.

After he has paid for his food, phone and medical treatment for the asthma he says he has contracted since starting work on the dusty site, he has 650 QR a month.

Supporting family

He has to give half of that to the recruitment agency in Dhaka.

"I am supporting elderly parents, my wife and a child," he says.

"I can't send them the money they need.

"I don't want to stay here but I can't leave. The company have my passport."

He adds: "We wake at 4 in the morning, get to work at about 6 and work until 5 in the evening.

"It takes an hour to get back to the camp.

"My room there isn't fit for humans - six of us share and there's no place even to sit and eat."

Qatar's national team have never reached the World Cup finals

On his safety helmet and safety pass, there is the name of Carillion.

Carillion says it uses 50 subcontractors in Qatar and that the company employing Imran provides labour to one of its subcontractors.

Carillion says it is "deeply concerned and surprised" by our findings and will be "conducting an immediate review of these claims to establish the position and take appropriate action".

The workers' camps lie between 10 and 20 miles from Doha centre.

We follow a bus that leads us to a camp used by another subcontractor company working for Carillion.

There are two Nepalis, two Indians and two Bangladeshis sitting on the floor eating.

Leg in plaster

No-one complains about the room in which are three bunk beds, but there are plenty of other complaints.

"I am telling you, sister, I did not get paid on time," says Rajiv.

"They would say that the company faced a loss on a project and so our salaries would be delayed."

The men say they get 750 QR a month and 200 QR extra for food.

Sanjay shows me a finger that was badly cut and mended crudely.

Although hired by subcontractor companies, these men have no doubt who they ultimately work for on site.

Fifa's decision to award Qatar the World Cup has been dogged by controversy

"I am working for Carillion. When I'm on the construction site, I don't get safety glasses or gloves," Sanjay says.

"My finger was nearly chopped off.

"I never got compensation for it, nor were my medical bills paid. I paid for the treatment myself."

Raju adds: "None of us get to keep our passports. I don't even know why."

There is a man in the room with a leg in plaster.

I turn to ask him how he got the injury when two men burst in, shouting.

Negative stories fear

They threaten to take the camera and yell at us, saying Carillion is their main customer and they are terrified that negative stories could damage their business.

We pretend to erase our material and they let us go.

Carillion says that "health and safety is at the very heart of our business, and practice on site follows standards that we apply in the UK".

It says subcontractors "must abide by Qatari labour law in respect of wages, living conditions and employment rights…. and we expect them to comply with Qatari law which prevents employers withholding workers' passports".

In another area of Qatar, the "Industrial Area", there are more camps for workers employed by a variety of local and international companies.

The Qatar Foundation Stadium is among those to be built for 2022

There are more Western Union outlets down one street than I have seen anywhere else in the world.

Sending money home is what it is all about for most of the 1.5 million migrant workers in Qatar.

They come from countries with some of the poorest people in the world - Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Philippines.

Late pay can be a disaster for families back home who might have to resort to crippling loans to survive.

But there is a worse kind of news.

"A lot of workers die because here in Qatar we are working on very tall buildings. Fifteen workers have died on the site I am working on."

Mahendra, 24 and from Nepal, tells me this as we chat alongside a makeshift football pitch in the desert sand.

1,000 deaths

More than 1,000 migrant workers have died since Qatar was awarded the World Cup in 2010.

Workers come off the pitch to give me their list of complaints.

A recurring one is the amount of money they have to give the recruitment agents who send them here.

"They gave me a contract for 18 months," says another Nepali, Kesang.

"When I got here, the pay was half what they promised me.

"I spent a year paying off the debt to the agent and was only able to send money back for the remaining six months."

Qatar has been sensitive to the criticisms levelled at it by groups like Amnesty International, which condemned the "callous indifference" to migrant workers, external.

Qatar 2022 is bringing in new regulations for stadium projects

The Emir Sheikh, Tamin bin Hamad Al Thani, has said he is "deeply hurt" by such accusations.

His father, the previous emir, set up the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development as a force for good for the country.

Ray Jureidini, a professor of ethics and migration, has been employed by it to offer recommendations.

He says Qatar's labour laws need urgent reform and that corruption and bribery at the recruitment level must be addressed.

He also says that international companies have a duty to get more involved and is critical of those which don't.

"They don't ask about the men supplied to them," he says.

"They feel they don't need to ask how the workers were recruited, whether they were trafficked, or whether they are caught in debt bondage or being exploited.

"I call this a corporate veil. It's as if the worker is not even there, is not on their books."

'Catalyst for change'

Farah Al Muftah has been appointed chairwoman of the workers' welfare committee at the offices of the Qatar 2022.

She says: "As a Qatari, it hurts me when I see people being unfairly treated.

"There are people who say that, because of human rights abuses, we should take the World Cup away.

"I think that actually defeats the purpose.

"If the aim is to improve the conditions, then why would you take such a great opportunity, a catalyst for change, away from the country?

"That will actually harm the progress that is being made."

This week, she is announcing a review of new regulations governing living accommodation and working conditions for the 1,500 workers employed on the World Cup stadiums and directly related infrastructure.

The new regulations include offering workers canteens and on-site laundry services.

Doha will host the 2019 World Athletics Championships

Critics would argue it is the Qatari labour laws that are the problem.

The hated "kafala" law ties a worker to the employer who gives them the job.

Whatever the grievance, a worker cannot change jobs or leave the country without an exit visa.

There is no minimum wage and workers are not allowed to form trade unions - 100 workers are currently facing deportation for daring to strike.

The abuses have been well documented by Amnesty International and others.

Sporting prizes

And yet, the sporting community keeps awarding Qatar its prizes.

Unless the decision is overturned at a review in March next year, Qatar will host the World Cup in 2022.

And, a few weeks ago, the emirate was awarded the 2019 World Athletics Championships.

Tens of thousands of migrant workers will be drafted in to complete what needs to be done before 2022.

The International Trade Union Confederation, which has been compiling the number of workers' deaths, estimates that 4,000 might die before the ribbon is cut on the final stadium - all for a football tournament.

- Attribution

- Published13 November 2014

- Attribution

- Published13 November 2014

- Attribution

- Published13 November 2014

- Published12 November 2014

- Attribution

- Published5 November 2014

- Attribution

- Published30 October 2014

- Attribution

- Published10 June 2014

- Published7 March 2014