'Focus and teamwork' got Bernanke through 2008 crisis

- Published

Mervyn King and Ben Bernanke have known each other for 30 years

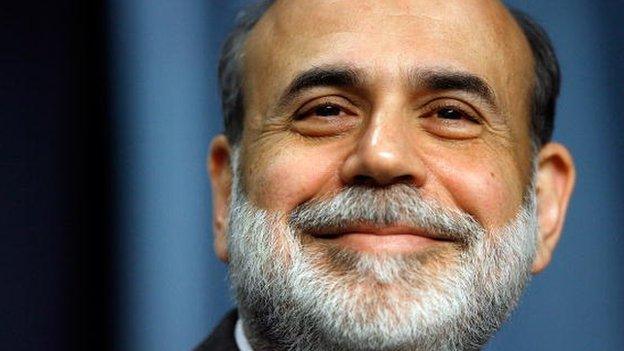

Ben Bernanke, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, tells former Bank of England governor, Lord King, how he faced up to the 2008 global financial crisis.

Thirty years ago two young economists found themselves in adjacent offices as visiting professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

What then, were the chances that the pair, Ben Bernanke and Mervyn King, would confront the challenge of the 2008 global economic crisis, not just as old friends but as, respectively, chairman of the US Federal Reserve and governor of the Bank of England?

"I'd say zero or less chance," explains Bernanke to Lord King, who is guest editing the Today programme.

Looking back at their time at MIT, Bernanke recalls he and King "established a relationship even then, talking about policy issues".

Speaking from his office in Washington, where Lord King visited him, Bernanke says: "It was good because when we were working together during the crisis we had the basis of a personal relationship which was useful."

As two of the world's most important central bankers, Bernanke and King were members of an exclusive group of economic paladins, whose policies and even personal pronouncements could sway the world's financial markets in seconds.

Both men agree their personal relationship and shared intellectual values played an important role in dealing with the crisis.

The lives of the two men have some intriguing parallels. Both grew up far from the centre of decision making - Bernanke in Georgia and King in Wolverhampton; both attended prestigious universities - Bernanke at Harvard and King at Cambridge; and both are avid sports fans - Bernanke following baseball and King enjoying cricket.

As Bernanke points out, monetary policy "is not an area that you can learn on the job".

"It's one that having that academic background is very helpful. There is very much a community of people interested in these issues."

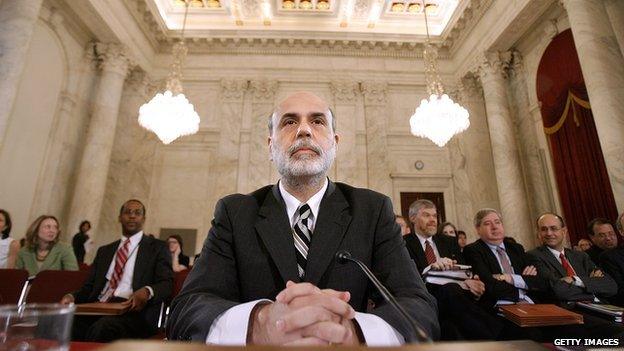

Ben Bernanke's time at the Fed saw him lead the US response to the 2008 global economic crisis

But, he adds, the existence of such a small group creates the danger of group think, and so decisions are often made by committees, not individuals.

"Monetary policy clearly has attracted a lot of academic thinkers and provided an intellectual and personal basis for people to work together," he says.

Meetings involving central bankers get a lot of attention, he says, though most of them are deadly boring and scripted in advance by bank staff. But a few are exciting.

The October 2008 meeting of G7 finance ministers in Washington, which threw the script out of the window by agreeing to pour billions of dollars of taxpayers' money into shoring up the global banking system and unblocking the global flow of credit, is a case in point.

At the time Bernanke would get into the office very early in the morning, and immediately go into a series of conference calls.

"There was in my office a red phone sitting on a coffee table, and every morning there would be six or eight people sitting around that phone with the loudspeaker talking about market conditions, what was going on, what we needed to be doing," he recalls.

"And there was a certain emergency feeling obviously to what was happening every day," he adds.

His work during the crisis was a mixture of dealing with unanticipated events plus more regular fare like delivering testimonies, speeches and hosting visiting dignitaries. Much of the time, he says, he was squeezing things in.

How, asks Lord King, did Bernanke cope with pressure or stress and what coping strategies does he recommend?

The answer is clear: take time off, do some exercise and do something different. And, most importantly, be focused on the task in hand.

Bernanke wanted to emphasise the Fed was "not just about one person". He says he encouraged "blue sky thinking" and would often brainstorm new ideas and approaches with his staff.

"I remain incredibly impressed by the quality of the work and the length and effort of time that the professionals at the Fed and the other central banks put into this," he adds.

Bernanke points to the increased transparency of the Fed as one important outcome of the crisis.

For years, he says, central banks were opaque, following the dictum of a former Bank of England governor, Montague Norman: "Never apologise, never explain."

Nowadays, he contends, it is very important to explain to the public and politicians how and why they were doing things. Plus why it's important. This adds to public confidence and is good for the economy.

Mervyn King served as governor of the Bank of England from 2003 to 2013

During the crisis, he says, the Fed was doing "complex and scary things" amid much uncertainty and fear.

It was hard, he adds, to explain to the public that things were bad but could be much worse.

"In the US, I think the understanding is much greater today than in 2008," he says.

Now at the Brookings Institution, a US think tank, Bernanke says life is much quieter after eight years of excitement. He is currently working on a book and reflecting on his 12 years in government "and things I didn't have time to fully work through" while at the Fed.

In addition, he is giving talks and reconnecting with the academic world as "a very small club of post-Fed chairmen," along with Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan.

And, asked by Lord King to list the most important qualities a public leader needs to tackle a crisis, Bernanke points to:

The intellectual framework to understand what's happening and devise solutions. Having a great team.

Being calm under fire and projecting confidence.

Being very collegial. More heads are better than one.

Mervyn King guest edits BBC Radio 4's Today programme on Monday 29 December, 06:00-09:00 GMT - or listen again online.

- Published31 January 2014