Where next for the eurozone after the Greek vote?

- Published

.jpg)

So where does the eurozone go from here?

Syriza's election victory raises some difficult questions for the other countries using the currency and for the European institutions.

The party's proposals represent a challenge to the austerity that has been a central feature of the eurozone's response to the financial crisis - bailout loans combined with spending cuts and tax rises to reduce borrowing needs and economic reforms to encourage growth.

For the architects of that response - especially the European Commission and Germany - the idea of renegotiating the terms and reducing the debt is an unpalatable one.

Germany and some other eurozone countries already have political problems with the bailouts - received by a total of five countries. Many voters resented the financial assistance, even though it was loans. Any suggestion that they won't be repaid in full will aggravate those concerns.

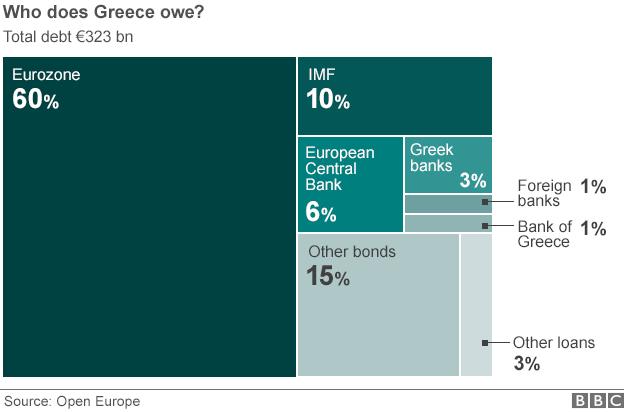

The key to the Greek burden does lie with the eurozone and its taxpayers.

Some 60% of the outstanding debt is bailout money provided either by the member states themselves or by the European Stability Mechanism, an official EU agency which gets its funds in the financial markets but is financially underpinned by the eurozone countries.

Another 10% is owed to the International Monetary Fund which is ultimately backed by global taxpayers. It doesn't generally do debt relief.

The European Central Bank accounts for 6%. It is banned from giving relief on that by EU law. The country's debt to private sector creditors has already heavily cut back in 2012. The remainder is a variety of creditors including banks, pension funds and other investors in Greece and abroad.

After Greece, Spain?

There is a fudge that could be used to ease the Greek debt burden, and it has already been used. That is to reduce the interest rate on its debts to the eurozone and extend the repayment period without actually cutting the nominal value of the debt to be repaid.

To give ground to Syriza could also be read as suggesting that the austerity approach was a fundamental mistake.

After all many economists argued that cutting government spending and raising taxes was exactly the wrong thing to do in economies that were already weak. Austerity aggravated the weakness, they argued, and so undermined tax revenue and exacerbated the government financial problems it was supposed to fix.

Another problem for Germany and those that share its view is that concessions to Syriza might embolden anti-austerity political forces in other countries.

Spain's Podemos party is a striking recent arrival on the political scene, but others will also be watching developments in Greece very closely.

Syriza supporters cheer after their party's election victory

Risk reduction

That potential for political "contagion" from Greece to other countries is probably more of a worry for the eurozone than a repeat of the kind of financial and economic contagion we saw when the crisis was at its most intense, in 2011.

That's not to say that type of danger is absent. But the eurozone does have measures in place the reduce the risk.

The key one is European Central Bank proposals to buy the debts or bonds of governments whose borrowing costs go too high. This is NOT the policy of quantitative easing announced last week as a response to deflation or falling prices.

It is a proposal targeted at ensuring that countries such as Italy and Spain do not face unsustainably high borrowing costs as a result of fears they might end up leaving the euro. It's a policy announced by Mario Draghi in 2012. The mere announcement had the desired effect. It hasn't been used, but it is there if needed.

But even if the eurozone can keep the lid on any financial market fears of a wider break-up, the possibility of Greece leaving can't be discounted.

The Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras says he doesn't want it and nor does Greek public opinion. Even Germany doesn't want it, though there is a limit to the concessions that Chancellor Angela Merkel and her Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble are likely to make.

So the odds are that some sort of compromise will emerge. It may well be messy and be slow to take shape. But then did the eurozone ever do anything that's difficult quickly or easily?

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015

- Published26 January 2015