In your irises: The new rise of biometric banking

- Published

Iris recognition technology is just one of the biometric measures that could be used to secure your bank account

When Apple started selling its iPhone 5S with a Touch ID fingerprint reading sensor, all of us entered the biometric age a bit.

Apple acquired the technology when it purchased AuthenTec in 2012.

Samsung followed quickly with its own version of the tech in the Galaxy S5 and soon-to-be-released S6.

With telecoms company Qualcomm promising to release a 3D-fingerprint reader shortly, having one in your pocket could become increasingly standard in the next two years.

And RBS and NatWest have recently announced that customers will be able to log on with Touch ID to do their banking.

German hacker Starbug - whose real name is Jan Krissler - is not impressed.

He hacked Apple's Touch ID roughly a day after its launch, replicating the last fingerprint that had touched the glass iPhone surface with kit that included a scanner, a printer, and a bit of glue.

And he followed this up in December by reproducing the fingerprint of German Defence Minister Ursula von der Leyen, using photographs from a press conference at a distance of about 10 feet.

Starbug believes that proper protection requires "two-factor authentication, based on two completely independent components from one of three methods: knowledge - password; possession - smart card; and biometrics."

Apple's iPhone 6 has Touch ID fingerprint authentication built into the home button

So something you know, something you have, and something you are.

"The problem with that kind used here," he says, "is that you probably will find all the 'secret' information of one method on the device used for the second method."

"So, if you are able to make a dummy finger from fingerprints found on the phone, the two factors are only worth one," he concludes.

Holding hands

The vulnerabilities in fingerprint recognition are not exactly secret. And so the race for alternative biometrics is on.

It is spurred by a new abundance of cheaply produced sensors - mostly from east Asia - and software connecting them with cloud services. Low interest rates also provide a rich environment for tech investment.

Barclays is bringing out finger vein authentication for UK business customers this year.

It is a technology Hitachi developed in Japan that is now being used in cash machines there and in Poland.

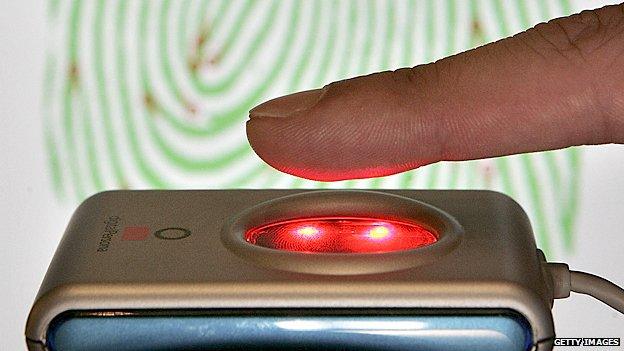

Fingerprint scanners like this have been around for a while - so Hitachi's VeinID looks beneath to find the blood vessels in your fingertips

Your vein pattern is established in the womb, and stable throughout your life, says Hitachi's Ravi Ahluwalia.

When near-infrared light is transmitted through your finger, part of it gets absorbed by the haemoglobin in your veins.

And so Hitachi's VeinID scanners can authenticate you by your resulting vein pattern.

Mr Ahluwalia says his company has explored finger vein authentication on trading floors in France and Northern Europe.

And British startup Sthaler is working with Hitachi and BT on a "pay-by-finger" solution it has trialled at several music festivals. It calls it FingoPay.

"You place your finger on [the] scanner, they'd confirm your name or last few digits of your credit card, and the payment is made in real time," says Mr Ahluwalia.

Barclays is experimenting with finger vein scanning

Vital statistics

Or if you don't fancy giving your bank the finger, other biometric tech coming to market includes the Nymi.

Produced by Toronto-based Bionym, it is a wristband which verifies identity based on your heartbeat's electrical pulses, which are unique.

And then there is a Dresden-based company, Cognitec, which, after an early focus on fingerprint technology, is now working on facial recognition, says biometric consultant Julian Ashbourn. It has been awarded a contract by the German Border Police.

In New York, a company called EyeLock is producing a commercial iris scanner it calls Myris. The company claims only DNA offers more accurate authentication.

But some working within financial technology think several of these biometric scanners are just a bit intrusive for banks and credit card companies to want to introduce them to ordinary consumers.

Fingerprints may be too easy to replicate to provide adequate security on their own

For these companies "the expensive and inconvenient part is actually challenging the user," says Dr Neil Costigan, an Irish cryptographer and chief executive of Stockholm-based BehavioSec.

"When they're asking where's the calculator in the drawer, or can you confirm your first pet - the user gets annoyed. With every step of security causing users to do something, a lot of payments fall off," notes Dr Costigan.

"It's a lot about easing the journey - only challenging the bad guy," he says. He also says voice recognition is promising for banks, precisely because consumers do not find it as "Big-Brotherish".

If you wish to push this to the extreme, there are start-ups experimenting with biometric implants - implanting an RFID [radio-frequency identification] chip under your skin, or a decomposable tattoo which may hold up for one to two months.

But most of the time, it's not so much biometrics that are the weakest link as their implementation, says Candid Wueest, principal threat researcher at the internet security firm Symantec.

"We've seen penetration testers, instead of hacking a fingerprint to get in a server room, just remove two screws to remove the fingerprint reader from the wall," he says.

Dr Neil Costigan, chief executive of Stockholm-based BehavioSec

"And then you can just get some device hooked up to the wire, and send a signal saying you've found a valid finger."

Governments and private institutions will often relax security rather than vex their consumers.

"The more people you need to get through, the more you tend to lower security," says British biometrics expert Dr Carol Buttle.

Who am I?

An alternative is behavioural biometrics - looking at the gestures and speed with which users key in their password, in a way they won't necessarily see.

When Danske Bank tried introducing a timer into its e-banking platform, it found that the speed at which a user filled out an online form could differentiate a real user from an imposter 97.4% of the time.

Many have predicted biometrics will cause the death of the password. Dr Costigan at least thinks devices like HSBC's physical Secure Key are on their way out, and credit cards, too.

"You don't expect people to have this very powerful mobile phone device, and then go off and search for a calculator," he says.

He believes Scandinavian banks, benefiting from closer co-operation in the banking sector, have led the way in applications featuring behaviour-based identification.

Britain is slightly behind, he says, followed by the US, with its larger number of small banks.

Iris eyes are smiling

At the end of the day, the best biometrics will be the least visible ones.

Some of these may turn out to involve wearable technology.

"If you've got a watch attached to you that's reading your biometrics, it will be useful," Dr Buttle observes.

Applying the spectrum of different possible biometrics to finance has led to a hotbed area for new start-ups.

Dr Stephanie Schuckers testifying on biometrics before the US House of Representatives

"The incorporation of Touch ID into Apple Pay - that's probably been the big game changer in the last six months," she says.

The major credit card companies agree that biometrics are very much on their radar.

"Probably 20 years ago, no one would've thought the phone would have the impact on banking that it's having," says Jonathan Vaux, executive director at Visa Europe.

"If I know the minute you land at JFK, because your phone is paired with your account and geolocation tells me you've landed - that should drive for a better customer experience," he says.

And Dr Stephanie Schuckers, a professor at Clarkson University and chief executive of NexID Biometrics, says hacking of the sort achieved by Starbug is well within the grasp of organised crime, but not easily scalable.

Perhaps we shouldn't rely on the humble fingerprint just yet.