Q&A: Tax credits explained

- Published

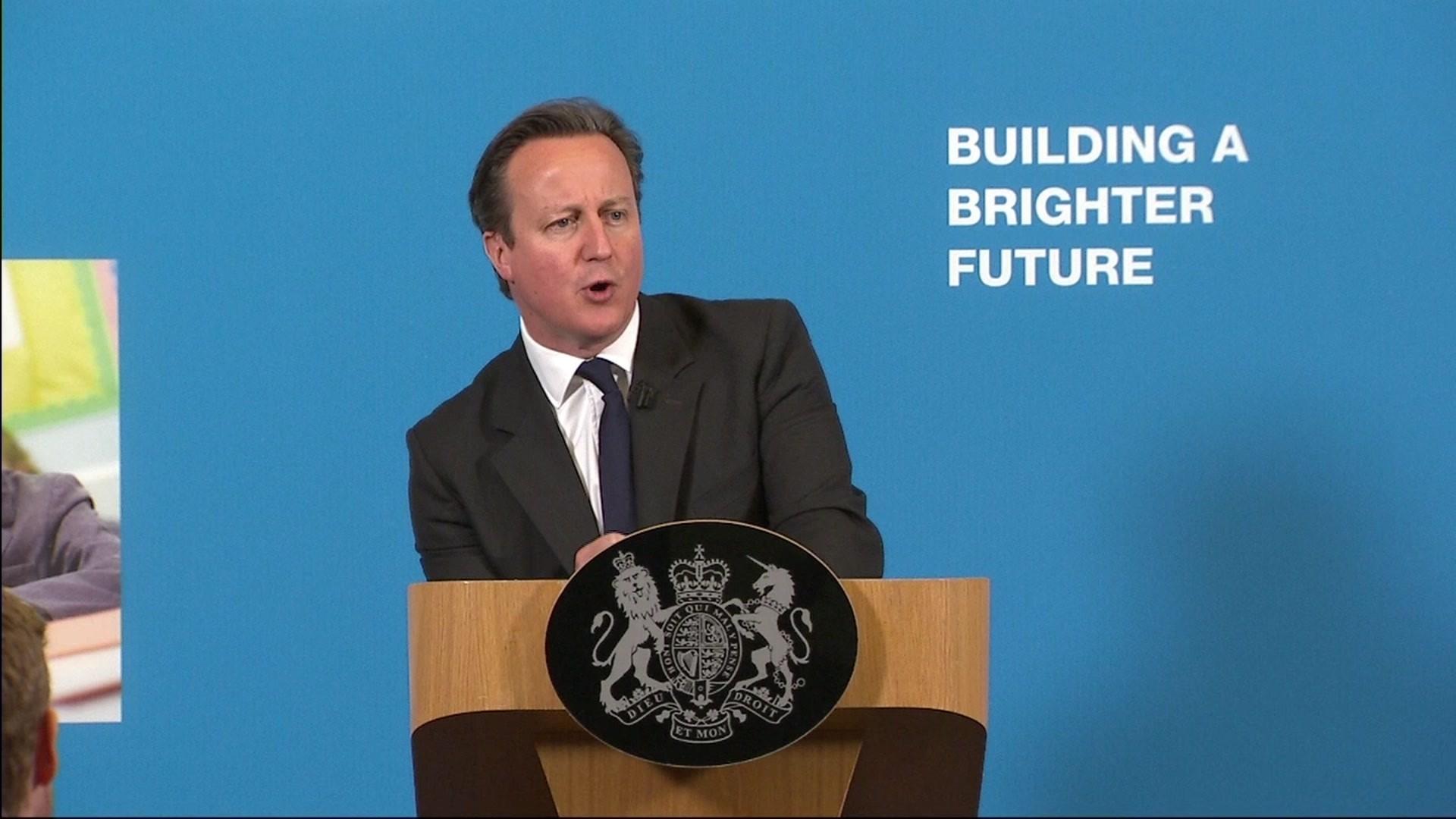

The government says it needs to find a further £12bn in savings from the annual welfare bill to meet its goal of balancing the books by 2017-18.

In September MPs voted in favour of tax credit cuts, but in October the plans were blocked by the House of Lords, which voted to delay the cuts and compensate the losers in full.

But what exactly are tax credits and how do they work?

What are tax credits?

Don't be fooled by the name: they are little to do with tax. Unlike tax "reliefs", people need not be paying any tax to receive tax "credits". Tax credits are essentially a means of re-distributing income by paying money to a) families raising children and b) working people on low incomes. To their critics, they are a handout. To supporters, vital to relieving poverty.

Why were they introduced?

Until the late 1990s there were benefits such as family premium, costing far less than the current system. In his first term as chancellor, Gordon Brown introduced Working Families Tax Credit (along with Disabled Person's Tax Credit and Children's Tax Credit) with the twin aims of helping families in low-paid work to make ends meet and lifting families out of welfare dependency by removing disincentives to work (sound familiar?).

The idea was that instead of seeing most of their benefits withdrawn as soon as they returned to work, people with families and those on low incomes would keep some or all of their benefit when they went back to work. In 2003 they were consolidated into Child Tax Credit and Working Tax Credit and increased in generosity.

What good, if any, have they done?

A lot. In fact: tax credits have played a big part in one of the biggest improvements in child poverty seen since the war.

Between 1998/99 and 2012/13 the number of children living in families below the poverty line (defined as less than 60% of the median wage in 2010/11 before housing costs) fell from 35% of the child population to 19%, external.

How much do they cost?

It's estimated the taxpayer will spend £30bn on them in the year from April 2015 to April 2016. That's 14% of the welfare budget (£220bn).

How many people claim them?

About 4.5 million, 4 million of whom have children. People may be eligible, broadly, if they earn less than £32,969. If a person's income is below this level and they also have children they'll be eligible for child tax credit. Eligibility for working tax credit depends on how many hours a person works.

How much do claimants get?

The average award of tax credit was £6,340 per year. But it can be far more than that.

Child tax credit claimants get £545 per year as a flat payment, plus £2,780 per child .

Then there is working tax credit. Claimants must work at least 16 hours if they are single, 24 hours a week if they are a couple with kids and 30 hours with no children. They get a basic of £2,010 plus extras. In addition, claimants may get up to £210 per week to pay for childcare.

So what's the maximum claimants can get?

It might be far more than their earnings. Take a single parent with three children, working 16 hours on minimum wage of £6.50 an hour. Their wage would be about £5,400 per year.

Child tax credit would be £8,885 a year. The basic working tax credit would be £3,970, including an allowance for being a single parent. But then add in the childcare element. At the maximum this is worth £11,000 a year. A total of £23,855 per year - more than four times what that single parent is earning.

This is why, for a single parent, it pays to find a job working 16 hours a week. But finding a full-time job is another matter. For every additional £1 a single parent earns, they will lose 41p of tax credit. So the incentive to work is there, but there is less of an incentive to work more than 16 hours.

Didn't chancellor George Osborne cut back tax credits as part of austerity measures?

Not at first. In the 2010 Budget the amount families were paid per child was increased, over and above inflation. However, in the last three years, working tax credit has been frozen and child tax credit increased by 1% a year.

So what does George Osborne want to do to them?

The Chancellor proposed lowering the earnings level above which tax credits are withdrawn from £6,420 to £3,850 and speeding up the rate at which the benefit is lost as pay rises - something MPs backed in the Commons. The changes would have saved £4.4bn.

What effect would that have on families claiming it?

Opponents of the changes said about three million families would have lost £1,000 a year under the chancellor's initial plans. The government said the majority of tax credit recipients would benefit from other policies, including increases in the personal income tax allowance, an expansion of free childcare and the introduction of the National Living Wage.

So what's happening now?

George Osborne criticised "unelected Labour and Lib Dem lords" for defying the will of the elected House of Commons when it was blocked by the House of Lords. But he also said he would "listen" to concerns raised and would set out how the proposed changes to tax credits would be modified in November's Autumn Statement.

The Work and Pensions Committee has also said Mr Osborne should delay the cuts. The group of MPs also warned there was no "magic bullet" to protect low-paid workers.

- Published22 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015

- Published22 June 2015