Does ad blocking herald the end of the free internet?

- Published

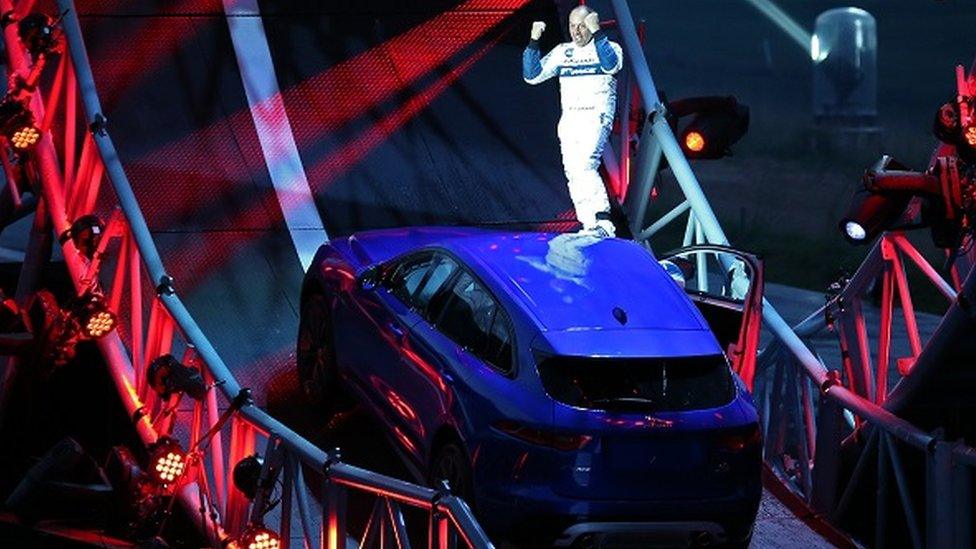

Will brands like Jaguar have to create more of their own content to bypass ad blockers?

Imagine you had to start paying to view content on all your favourite websites.

Would you give up on the internet completely or happily stump up for good journalism and entertainment?

These are the choices we could be facing if ad blocking programs go mainstream.

This is because advertising revenue underpins about 90% of everything we see online - it's the internet's fundamental economic model.

Yet Apple's decision to allow its iPhone and iPad Safari browser to block ads through the use of third-party software extensions could seriously undermine this model, analysts believe.

Apple's decision to allow ad blockers onto its Safari browser could change internet economics

"Ad blocking is a threat to the whole advertising industry," says David Frew, senior programmes manager for the Internet Advertising Bureau trade body.

"It's possibly heralding the end of online advertising in its current form," he says. "It's essential people understand that online content isn't free - there's a value exchange. Facebook is monetising you - your data is valuable."

Internet browsers have given users the ability to block pop-ups - and therefore pop-up ads - for years, and there are a number of ad blocking programmes already on the market, such as AdBlock, Adblock Plus, uBlock and Adguard, already used by tens of millions of people around the world.

AdBlock claims its program can block all ads, including those on YouTube and Facebook

But now that a global brand like Apple has weighed in, the practice could become much more popular, particularly on mobile, some in the publishing and advertising industries believe.

'A lot of junk'

Brian O'Kelley, chief executive of AppNexus, a digital advertising technology firm, believes that websites only have themselves to blame for this ad backlash.

"A lot of websites have gotten greedy - on some home pages about 50% of the screen area is taken up with ads. A lot of junk is thrown on there," he says.

"Ads are supposed to be attention getting but they shouldn't be intrusive or annoying."

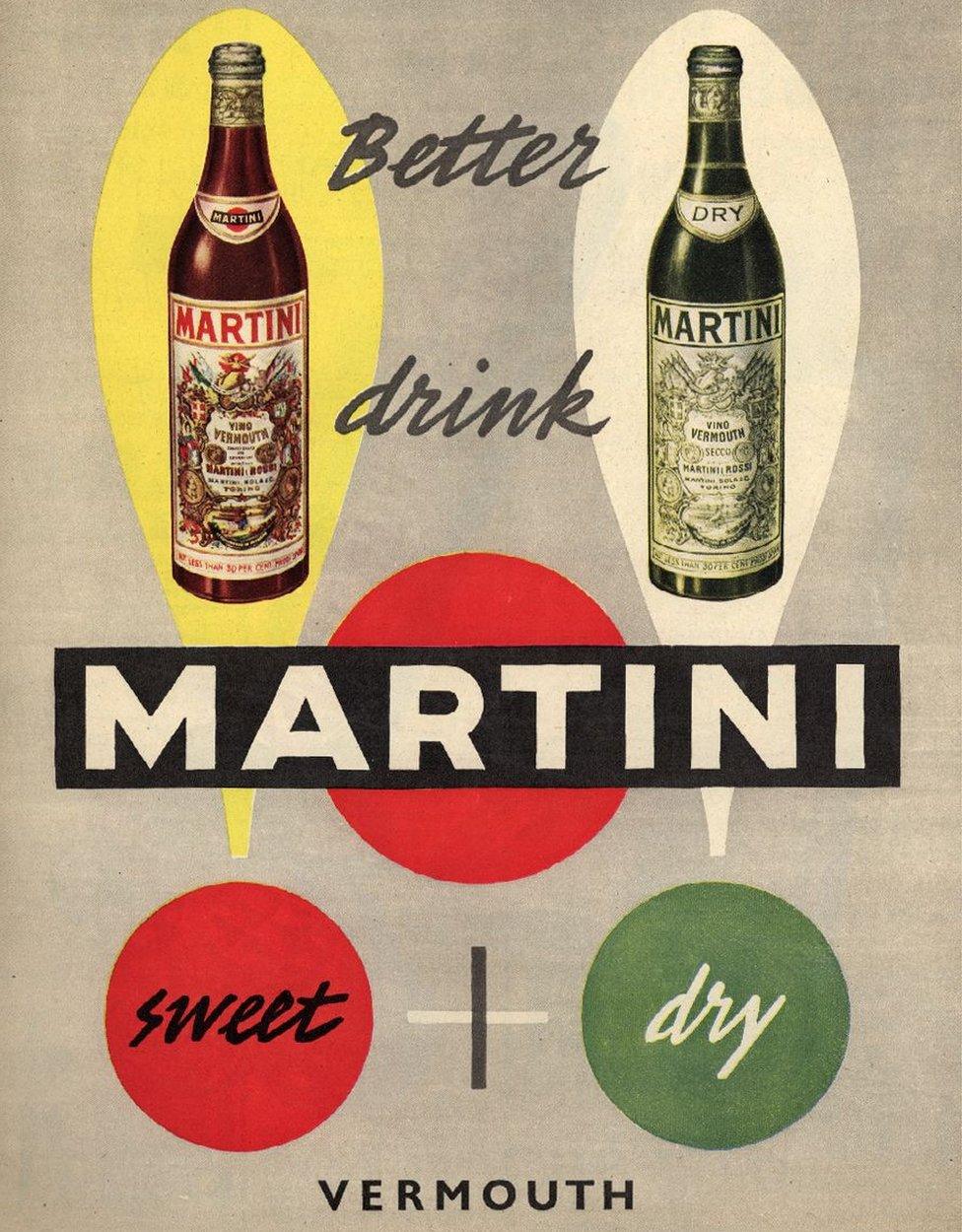

Adverts have always underpinned commercial publishing, but for how much longer?

Daniel Knapp, senior director of advertising research at consultancy IHS, agrees, saying: "Consumers are fed up with interruptions and ads that affect the viewer experience. Ads also increase data usage and reduce battery life on mobile."

But there is a paradox in our feelings towards ads, believes Mark Pinsent, managing director of digital marketing agency Metia.

"People say they don't like ads and as soon as you give them the ability to avoid advertising, they will.

"But we often like to chat about our favourite ads. The problem is there's a lot of bad ads out there."

'Hard conversation'

So if consumers begin blocking ads en masse, how will online publishers cope with the inevitable cut in revenue, and how will advertisers reach their audiences?

"There'll be fewer ad transactions and less money, but it's not going to zero. It just makes the pie smaller for everyone," says Mr O'Kelley.

In his view, publishers and content producers will have to have a "hard conversation" with consumers and persuade them not to use ad blockers.

An eight-story digital advertising billboard in new York's Times Square shows the lengths advertisers will go to to grab our attention

"Consumers should have a choice over what kinds of ads they want to see, how fast they want them to load, and how much personal information they are happy to share," he says.

"When you visit a site with an ad blocker on there should be no option where you can get the content for free."

'Big disruptor'

But how realistic is such an approach in a world where free internet content has been taken for granted and the subscription-based paywall model has succeeded only for specialist publications?

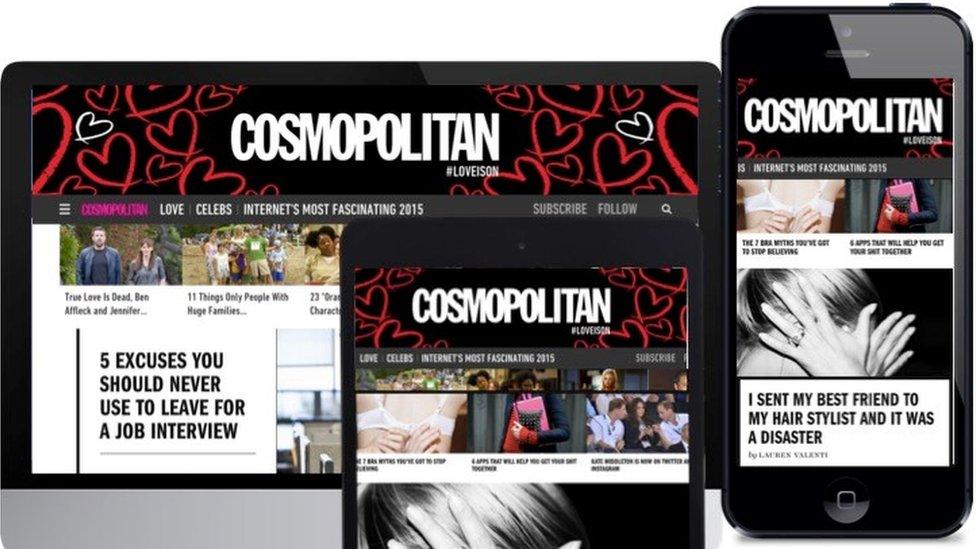

Darren Goldsby, chief technology officer for Hearst Magazines UK, publisher of well-known titles such as Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping and Esquire, admits that ad blocking is "as big a disruptor for us as the internet was when it came along".

Ad blocking is as big a disruptor for us as the internet was when it came along

"Ad blocking is a threat and the number of ad blockers is likely to increase. But that means we have to work harder to provide content in a commercially successful way that people want to read," he says.

This is likely to mean more so-called "native advertising" - sponsored content, advertorials, branded micro-sites, and so on - that can't be blocked by ad blockers, says Mr Goldsby.

And advertisers are already learning to use social media as a way of engaging with consumers, presenting content that is entertaining and shareable, says Mr Pinsent.

Hearst says its UK digital titles reach 15 million adults

For example, Jaguar recently videoed its new F-Pace four-wheel drive car performing the world's biggest ever loop-the-loop. It made newspaper headlines.

"They then used targeted paid-for social media to get that video in front of people who would find it interesting," he says. "They did that without going through any traditional publisher.

"Brands will increasingly become their own content producers."

Blurred lines

But as publishers resort to more of this native advertising and branded content to recoup lost digital ad revenue, what does this mean for independent journalism?

"As soon as you start blurring those lines between journalism and brand sponsored content it becomes very dangerous because consumers may be influenced without being aware of it," warns Mr Pinsent.

Once consumers understand that they may have to pay for an ad free online experience, ad blockers may wane in popularity, particularly if the other alternative is a website full of commercially biased editorial.

In the battle for our eyeballs, many analysts think Facebook and Google will come out victorious

But some observers believe the rise of ad blockers provides an opportunity for consumers to strike a new deal with publishers and advertisers.

"A new model is to put users of the internet in control of their own data. Let them decide who they trade it with and for what reward," says StJohn Deakins, chief executive of CitizenMe, a group helping consumers take control of their own data and monetise it.

Others believe this shift in internet economics will simply put more power in the hands of Facebook, Google and, increasingly, Amazon.

"By 2020, 70% of European online advertising will be controlled by Facebook and Google," says IHS's Daniel Knapp.

"They're building closed ecosystems to lock in content and advertising. They control the audiences."

Is it time for those audiences to wrestle free from such control?

You can follow Matthew on Twitter: @matthew_wall, external