Pacific islands want a bigger share of fishing income

- Published

WATCH: Kiribati fishes for tuna wealth

As huge schools of tuna cut swiftly across the Western Pacific on a migration course that spans thousands of kilometres, they cluster by size.

Massive adult yellowfins swim together, while juveniles group separately and swim with adult skipjack of a similar size.

Schooling confuses predators and makes it less likely that any single fish will fall victim to one. And bigger numbers mean more eyes are on the lookout for a meal.

Fishing is the best economic hope for the tiny island states that dot this part of the Pacific. And much like the fish they pull from the ocean, they've learned the benefits of swimming together.

The bulk of the fishing in the Pacific is sold by treaty to other countries, with the host nation collecting an access fee for each day of fishing.

Fishing licences in Kiribati account for more than half of the government's revenues

Since the Pacific island nations started negotiating as a bloc five years ago, they've found themselves in a much better position.

Effectively, eight Pacific countries including Kiribati, formed a cartel, banding together to wield their market power to negotiate a better deal, and it's working.

Their revenues from fishing rights have increased from $100m (£65m) to $430m over the past five years, according to the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency.

So how can these tiny states, mere specks on a map of the vast Pacific, wield this kind of market power?

Sprawling economic areas

In truth, they're not as small as they seem.

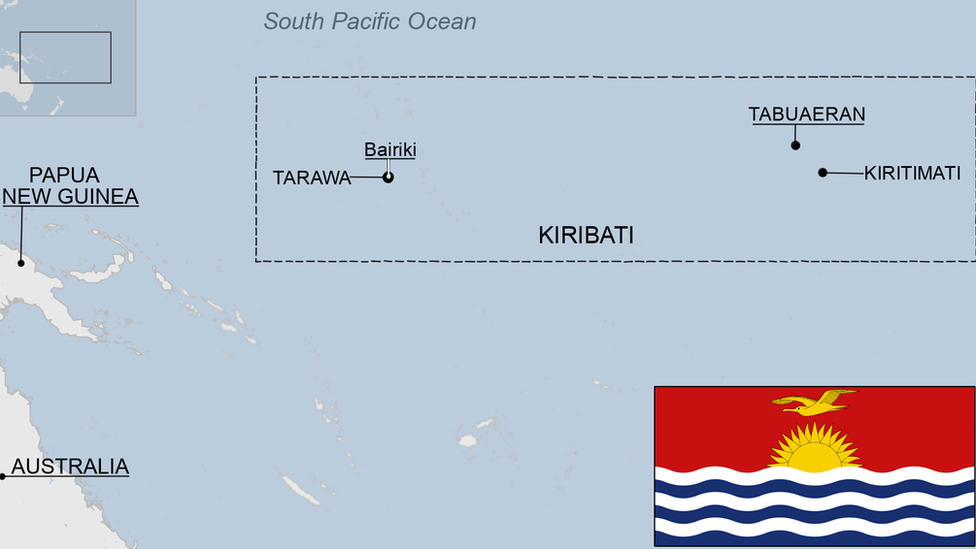

Kiribati is made of 33 atolls. The most populous island of the vast archipelago nation is Tarawa

Every nation's exclusive economic zone spreads roughly 370 kilometres (230 miles) from its shores in every direction. So a country of widely-scattered, tiny atolls can have massive fishing grounds, even if it doesn't have much land.

Kiribati's land area is only 810 sq km, roughly equal to the city of New York or about half the size of Greater London, but its exclusive economic zone is bigger than India (about 3.5 million sq km).

Together, the small island states control so much ocean that they've enacted a rule forcing their customers to choose between their waters and the open ocean. Most opt for the former.

But controlling enough of the resources is no guarantee of an effective cartel. Cartels take a considerable amount of political will and discipline.

Members of the most famous one, Opec, often break ranks, and there's some evidence of discord here, too.

"Certainly we encounter more and more where it becomes more difficult to operate as a bloc. The easy wins have been won already," says Wez Norris, the deputy director-general of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency.

The cartel of eight Pacific countries include Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Marshall Islands and Palau

Looking for better deal

Last year, Kiribati largely opted out of a regional $90m deal with the US, drastically cutting the number of days US boats could fish in its water under the treaty.

Kiribati's President Anote Tong says there's a practical element to it.

In previous years, they ran out of fishing days allowed under the treaty, and had to buy some from one country in order to give it to another.

But Kiribati might also be looking for a better deal.

"All we're saying is we would reduce our contribution of vessel days to the US treaty. If the US boats want to fish in our waters, they can buy direct from us," he says.

Regardless of whether cartels stick together, national competition and consumer watchdogs take a dim view of them, because they usually jack up prices.

Trade commissions or consumer bodies might step in, for example, if supermarket chains or petrol retailers were jointly setting prices or conspiring to drive rivals out of business.

Of course, there's no watchdog that can stop co-operation between governments.

But the small Pacific states can scarcely be accused of predatory trade practices given how much fishing wealth flows out of the region.

Kiribati's fishing licence income of $75m is expected to be more than double its tax revenues this year

Money in processing

The real money is not in selling the raw materials, it is in processing.

Some years, Kiribati will keep only 5% of the wealth from its fish, although the average is closer to 10%.

President Anote Tong says if every fish caught in the country's waters was processed domestically, the country's gross domestic product would double or triple many times over.

"All the fish is now being taken to Bangkok. Imagine all the jobs it's creating over there, but not here," he says.

"So our objective is, and I think it's fair, that we want the processing. We want greater participation in the industry. Not just be the source of the raw material."

Kiribati is doing something about it.

About 300 people work at Kiribati's fish processing company on Tarawa

Every Wednesday, longline fishing boats glide across the startling blue lagoon waters and dock at Tarawa, the main island.

Workers haul massive yellowfin and bigeye tuna from below the deck, throw them over their shoulders and march up a flight of stairs before lifting them onto the docks. Then, they're loaded into massive ice-filled tubs, and taken down the dock to a processing plant.

This facility, run by Kiribati Fish Limited, employs 200 people, in addition to 100 who work on the boats. That's no small achievement in a country where unemployment tops 30%.

Still, it faces massive challenges.

Remote location hurdles

The same geography that gives these states such large fishing grounds ensures that they're smaller than their competitors and a long way from the markets they serve.

"There's more cost on labour and more cost on freight because the location is very far from the market," says Riakaina Teiwaki, who's the firm's assistant general manager.

"This makes the product more expensive."

The island state's remote location in the middle of the Pacific makes processing fish more expensive

Fish processing plants in the Pacific have a patchy record. But Mr Norris of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency is optimistic that there's a future in them.

There have been "a number of failed ventures in the region over the past 30 years." he says. "It's just a matter of learning from mistakes of the past and applying proper scrutiny."

And Kiribati desperately needs the money.

The low-lying atolls that make up this country are among the world's most vulnerable to climate change, and President Tong says this is perhaps the only way for Kiribati to build its resilience.

- Published5 November 2015

- Published26 January 2024

- Published24 September 2015