Saudi Arabia: Can the country adapt to cheap oil?

- Published

Infrastructure projects such as new metro lines may be affected by record low oil prices

Events of the last week in Saudi Arabia might not seem indicative of a government on the path to liberalisation. But when it comes to the economy, the oil rich kingdom is primed for reform.

The rising tension between Saudi Arabia and Iran has distracted attention from what was already becoming a fascinating story. In Riyadh there seems to be a quiet revolution underway in attitudes towards some of the fundamentals that have long underpinned Saudi Arabian society.

In December's budget we saw the first steps in a major economic reform plan, the rest of which is expected to be announced in January. The aim is to ensure political stability while the country adjusts to a much lower world oil price.

These reforms are "a necessity and not a luxury," according to the former Saudi petroleum ministry senior advisor, Dr Mohammed al-Sabban, who spoke to me from Riyadh.

Difficult times

Cautionary tales abound of what can happen if rulers ignore people's economic needs: one need only look across the region, to Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Syria, according to one Saudi-based academic, who spoke to me privately.

Ibraheem al-Jardan, business development manager of Riyadh-based investment firm Dayim Holdings agrees: "Economic growth is strongly linked to political and social stability - particularly in this part of the world, at these difficult times."

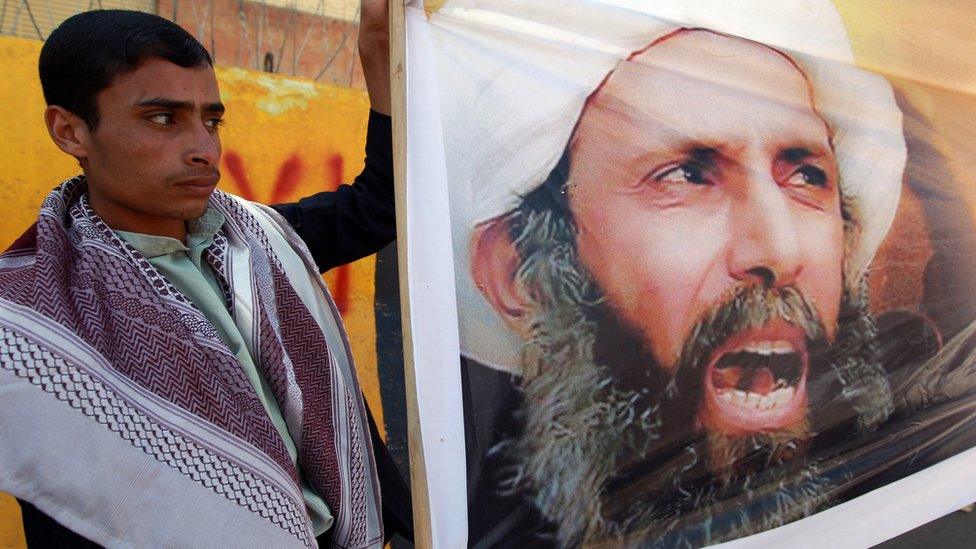

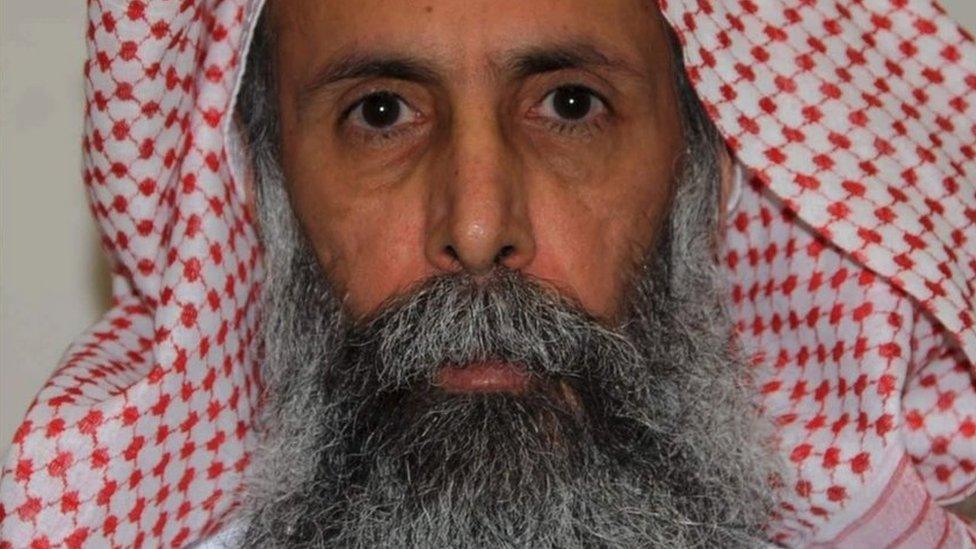

News of Saudi Arabia's execution of Sheikh Nimr has prompted an angry response from Shias across the region

Saudi Arabia has avoided any such political discontent or extremism so far through generous state hand-outs and by imposing almost no taxes but it has a bloated public sector and a history of waste and government largesse it needs to address.

Forcing their hand now though is the low oil price.

While in the past oil revenues could be used to lubricate the generous Saudi state machine, the country's income from oil fell by 23% last year, highly significant in an economy where around 73% of total revenues come from oil.

And there are fears that, with no prospect of higher oil prices any time soon, the tacit social contract: material comfort for limited political freedom could be at risk. As a result fundamental long term changes are required.

Cutbacks

King Salman has made a brave start.

Risking the displeasure of citizens, as the December budget was announced, he raised the price of subsidised, cheap petrol 40% overnight.

Saudi Arabia is planning to limit its dependence on oil

More is expected. There are plans to decrease other subsidies, reduce the growth of public sector salaries and limit the country's dependence on oil.

It's a major shift. Despite positive economic growth, the kingdom's conservative rulers no longer think huge cash reserves and over $150bn (£100bn) of annual, oil-fuelled state revenues are enough to maintain the high levels of spending on education, healthcare, military and security services, to which they remain committed.

As a result, even before December's announcements, non-essential spending had already been cut.

Transport schemes in a number of smaller cities have been postponed or scrapped, along with plans for a few trophy projects, like football stadiums. More such cuts are expected.

Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (L) is one of those spearheading the current reforms

Another area to watch will be the renewable energy market.

Much-anticipated plans for investments in solar power are expected soon, as well as announcements on nuclear and wind power.

Shifting towards renewables is a win-win. It creates jobs and reduces the amount the government spends on subsidising Saudis' consumption of oil.

According to Jadwa Investments, domestic energy subsidies can cost the government around 10% of GDP a year.

Why won't oil producers cut production?

During the 1980s oil glut, Saudi Arabia did cut production, but other producers failed to follow suit.

Once bitten, twice shy, Saudi Arabia will now only cooperate in a joint system of production cuts with states including Russia and Iran, a policy since 2014 reiterated to me this week by former Saudi petroleum ministry senior advisor, Dr Mohammed al-Sabban.

""Saudi Arabia has approached several large oil producers from OPEC and non-OPEC countries to co-operate in cuts to achieve market stability. Their answer so far is not very positive," he said.

The low oil price also hurts the economies of Saudi Arabia's political foes and it intends to continue to produce as much oil as their quota will allow, stockpiling any excess supply on ships.

"Their policy makes complete sense; they have nothing to gain from cutting," according to Ann-Louise Hittle, head of oil market analysis at Wood Mackenzie.

Dr al-Sabban predicts other big oil producers will eventually "learn the hard way and will come to Saudi Arabia asking for a joint solution."

But as his country now digs deep in to its cash reserves, he conceded: "I wish they had come forth a long time ago."

Job opportunities

At the time of the December budget, ministers insisted that income tax, which has never existed in Saudi Arabia, would not be introduced. But other taxes will be sought, likely to include taxes on "harmful goods such as tobacco, soft drinks and the like," according to the Ministry of Finance's budget statement.

Saudi women at the first annual Bab Rizq Jameel - a job fair for young Saudis in Riyadh

The statement also trailed "plans to privatise a range of sectors and economic activities".

Some state assets are already run as semi-private companies but consultants McKinsey warn that without further structural changes to the economy there will be a "rapid economic deterioration" over the next 15 years.

That is because of a pressing need for more jobs for a growing Saudi population.

At present, there are around 10 million foreigners working in Saudi Arabia, which has a population of roughly 30 million.

Last month, the Finance Minister Ibrahim al-Assaf said that the hiring of foreign workers would now be "more selective". Rules are already in place to make it easier for companies to recruit Saudis over expats.

Visitors to Saudi Arabia's car show last month. But domestic energy subsidies have been costing the country up to 10% of its annual GDP

Speaking from Riyadh, McKinsey's senior project manager, Tom Isherwood, told me one solution would be for more Saudis to be employed in the tourism sector, which was an "untapped opportunity for growth" by going beyond just religious tourism in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, to undeveloped beaches and picturesque sites across the country.

Whimper or bang?

But there are those who doubt anything will really change.

The business community has been calling for reforms for years but the state has been held back by institutional, consensus-based decision-making in the country.

Political analyst Crispin Hawes, from Teneo Intelligence, expects "more of a whimper than a bang," when the new economic plan is announced. He points to the government's generous hand-out of around $30bn to state players in January 2015, to greet the arrival of the new king, which also helped cause last year's record budget deficit.

Some believe the threat of jobless young people turning to extremism will cause Riyadh to speed the pace of reforms

In his view it was "out of all proportion, simply to maintain levels of domestic stability," as an example of the attitude of those in power.

Others believe that the momentum for change is there.

"Economic reforms are perhaps being expedited by the low oil prices, but they haven't just started as a result of it. There has been an on-going strategic plan for economic reform for a long time now, but Saudi moves at its own pace," said Amit Marwah, head of strategy and investments at Riyadh-based Dayim Holdings.

Some believe the threat of jobless young people turning to extremism will cause Riyadh to increase the pace of the reform process. And there is already a new generation of younger politicians spearheading the reforms, including the King's favourite son, 30-year old Mohammed bin Salman.

One insider described him to me as "a very serious visionary" and said the country will soon be experiencing a "totally different way of doing business" with strict targets and timetables for each task.

In that sense, a low oil price may turn out to be more of a blessing than a curse for those in favour of change.

- Published6 January 2016

- Published2 January 2016

- Published2 January 2016

- Published7 December 2015

- Published19 January 2015