Just how low can oil prices go and who is hardest hit?

- Published

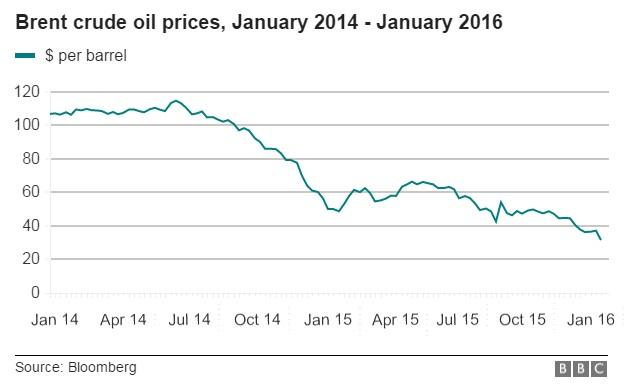

Oil prices have fallen again, sinking below $28 a barrel.

The price of Brent crude fell to $27.67 a barrel at one point, its lowest since 2003, while US crude fell as low as $28.36.

Many analysts have slashed their 2016 oil price forecasts, with Morgan Stanley analysts saying that "oil in the $20s is possible", if China devalues its currency further.

Economists at the Royal Bank of Scotland say that oil could fall to $16, while Standard Chartered predicts that prices could hit just $10 a barrel.

What are the factors have caused the price to sink below $30 a barrel - and what could spark a recovery?

What are the main reasons behind the fall in prices?

In a nutshell, it's down to too much supply and too little demand.

China's economic slowdown has curbed appetite for commodities in general, while Saudi Arabia, which produces a third of the Opec cartel's output, is keener on preserving its market share than it is on cutting production to boost prices.

At the same time, the rise of the US as a shale oil producer means it now imports less oil, adding to the glut on world markets.

This makes life harder for other non-US, non-Opec producers, who are facing cutbacks, particularly in the North Sea.

Is North Sea oil production viable at less than $35 a barrel?

Big oil companies such as BP, Shell, Total and Exxon Mobil have weathered the storm by cutting back on billions of pounds of investment, and thousands of jobs have been cut.

However, Jeremy Batstone-Carr, chief economist at Charles Stanley, warns that further price falls could really start hurting the big firms.

The first clue that they are starting to suffer, he suggests, will be cutting dividend payments to investors - something they have avoided so far.

Meanwhile, Alan Gelder, of oil analysts Wood Mackenzie, says many North Sea oil operators are "beginning to really feel the pain" at current prices.

He says firms can just about survive as many North Sea operators have already cut costs. But Mr Gelder warns that "there is no money left for future investment".

How about US fracking and shale oil operators?

Paul Stevens, professor emeritus at the University of Dundee, and a Middle East specialist, says the price of oil could theoretically fall to as little as $20 to $25 per barrel.

Why? It may be an unusual view but he thinks most US shale oil producers can tolerate current oil prices.

They may make a small loss - he estimates the cost of production at about $40 a barrel for shale producers - but until the price falls to around $25 a barrel they will keep producing, Prof Stevens says.

Mr Gelder, however, does not think many US shale operators can continue production with prices below $50.

"There are some sweet spots in the US where some operators are able to keep production going at lower levels, but it's not economic at under $30," he says.

There is also another much bigger problem than the future of fracking in the US.

"An awful lot of oil producers can't survive at these levels," Mr Gelder says. "Venezuela, Algeria, Nigeria are facing serious financial problems and political unrest with people out of work and prices rising."

How much oil is being bought at these prices?

There is so much oversupply globally that countries are running out of storage. The US, which is thought to have among the largest storage facilities in the world, has nowhere left to keep it, says Prof Stevens. And it's not the only country.

"Storage is pretty much full and people are already talking about buying tankers as floating storage," he says. "But if supply continues to outstrip demand, then the only thing that you can do with the oil is sell it, which inevitably pushes the price down."

Mr Gelder takes a different view, suggesting it is not entirely clear whether US storage is completely full. "We know about US and European storage levels, but India and China are strategically storing oil for supply disruptions."

Mr Batstone-Carr adds: "Without a marked reduction in output nothing will change, and we have to wait until June for the next Opec meeting before we might see a reduction in quotas. And all of this comes at a time when economic activity is on the back foot, signalling there's not a lot of demand out there."

Professor Stevens warns that the collapse in prices is the result of oil being "freely traded for the first time since 1928".

That, he says, is because Saudi Arabia has decided not to cut production to support prices - unlike during previous oil gluts.

Saudi Arabia v Iran: What could it do to oil prices?

It is just over four years since the US imposed sanctions on oil imports from Iran, helping to bolster prices and allowing Saudi Arabia to grab market share that it is now very reluctant to surrender.

A report from Wood Mackenzie says that the Saudis would not cut output to make room for Iran, which could begin exporting oil in the next few weeks, according to some sources.

"Unless other producers such as Russia, Iran and Iraq agree to reduce their oil production, Saudi Arabia has consistently stated since the November 2014 Opec meeting, it has no intention of cutting its supply to support oil prices," the report says.

"The current ramping up in tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran only further confirms our view that Saudi Arabia is unlikely to cut its output to help Iran regain market share."

Prof Stevens says tensions in the Middle East are "as high as you could have them without having outright war. I don't think things have been as bad since 1918 and the fall of the Ottoman Empire."

Such uncertainty normally sparks an oil price spike. But apart from a rise over the New Year, prices have continued to slide.

Mr Gelder says most oil traders shrugged off the possibility of Saudi Arabia and Iran squaring up to one another in a way that could seriously affect supplies.

And with demand for oil weakening, especially in China and emerging markets, there seems little reason to expect that prices are set to rise any time soon.

What does all this mean to me?

It means lower petrol prices, although what you pay at the pump may not fully reflect the oil price drop. Bear in mind that excise duty and VAT make up nearly 60% of the price of a litre, and that isn't coming down any time soon.

Obviously if people are spending less at the forecourt, they have more money to allocate elsewhere, and that is a potential boost to the economy.

However, if petrol-driven cars cost less to run, that means there's less incentive to invest in alternatives, such as electric vehicles, so in the long run, low petrol prices could be bad for the environment.

Additional reporting by Tom Espiner.

- Published19 February 2016

- Published6 January 2016

- Published5 January 2016

- Published12 January 2016