A tale of two homes: How warm houses change lives

- Published

Les Fawcett says insulation doesn't just keep people warm, "it leaves pensioners with a bit of cash in their pockets"

John Flynn from Hartlepool is 72. He's paying £180 a month to keep warm this winter in his north-facing end-terraced house.

Les Fawcett from nearby Middlesbrough is 76. He's paying just £45 a month to keep his home cosy.

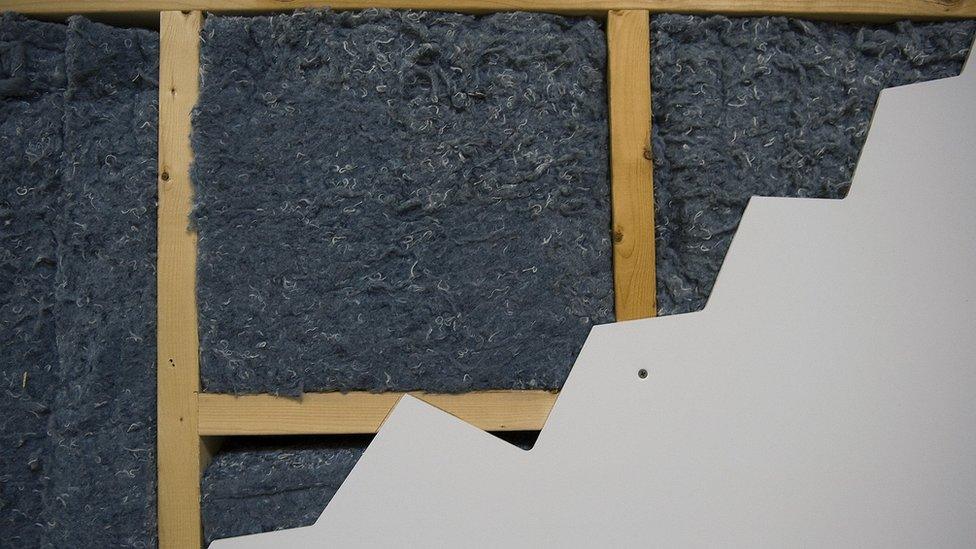

What separates the two is not a greedy energy supplier - it's four inches of wall insulation.

Both men are owner-occupiers living on pensions. Les had his solid walls clad free of charge under a government scheme, but the public money ran out before John could benefit.

John can't afford to insulate his solid walls out of his pension - so he ends up paying extra on his heating bills instead.

They both agree insulation is the unspoken factor in the UK's controversy over high fuel bills.

"The cladding's been the best thing that's happened round here," Les told me. "It doesn't just keep people warm, it leaves pensioners with a bit of cash in their pockets instead of borrowing from their daughters. It's changed people's lives."

Cheap prices, high bills

The UK overall has some of the cheapest energy prices in Europe - but among the highest bills, because homes are so poorly insulated.

This harms people who are fuel-poor and undermines the UK's climate change targets.

To achieve its legally-binding emissions cut of 80% by 2050, the UK needs a radical overhaul of existing housing stock - most of which will still be in use by mid-century.

The government is promising £640m a year for energy efficiency in homes. It says it's committed to combating fuel poverty and climate change, and aims to upgrade well over 200,000 homes per year.

John Flynn can't afford to insulate his walls

The right-leaning think-tank Policy Exchange, external (PX) says to insulate enough homes, ministers need to spend twice as much.

PX, along with many other energy commentators, wants the Treasury to make insulation a priority under its infrastructure strategy.

It says improving home efficiency creates many jobs; combats fuel poverty; reduces air pollution; minimizes carbon emissions; cuts fuel imports; benefits the balance of payments; and reduces the need to build new power stations.

Levy

"It's pretty much a no-brainer," said Richard Howard of PX. "Bringing people's homes up to standard is incredibly good value for money.

"We don't typically think of housing as infrastructure like we think of roads and railways - but we've got to change the way we approach this: housing is critical infrastructure."

The UK needs a radical overhaul of existing housing stock if it is to meet emissions targets

There is wide support for that view, although Len Shackleton, at the free market Institute of Economic Affairs told us: "Even quite big cuts in domestic energy would not make much of an impression on total energy use.

"It's disappointing to see another single-issue brigade arguing for yet more public spending as the best solution to rising energy bills."

The main cash for refurbishing the homes of fuel-poor people in England comes from a levy on everyone's bills. The works are carried out by energy firms under the Energy Company Obligation (ECO) scheme.

The government recently cut funding for ECO (along with cutting renewable energy schemes) to save around 82p a week on people's bills after complaints that energy costs were too high.

Things are different in Scotland, where improving homes has been made a National Infrastructure Priority.

A Scottish government spokesman said: "We will provide support to all buildings in Scotland - domestic and non-domestic - to improve their energy efficiency over a 15-20 year period.

"This commitment provides certainty to the supply chain and makes it the norm to invest in energy efficiency."

In Wales and Northern Ireland, too, taxpayers' money is used to promote insulation to prevent the levy on bills swelling too far whilst ensuring insulation gets done.

Fuel poverty

The Energy Minister, Lord Bourne, recently told MPs that the ECO scheme would be re-focused to ensure that ministers met their targets on tackling fuel poverty by 2030.

But he baffled professionals by saying that details of the replacements for ECO and the Green Deal insulation scheme would not be available for 15 months.

The insulation industry says this will further undermine its ability to plan work, and will push up costs.

Lord Bourne said: "What we're hoping to do by ensuring that the sole criterion after 2018 is fuel poverty is to ensure that households that can be identified as in fuel poverty will then be prioritised by the energy companies."

The UK has some of the highest heating bills in Europe because homes are so poorly insulated

But targeting the fuel-poor presents problems. First, they are often hard to locate. Second, there's the issue of the practicalities - and a question over who pays and who benefits.

The bill for exterior cladding is much cheaper if whole streets get wrapped in foam boards at the same time.

But this typically requires public cash to subsidise owners for making improvements, which will in turn reduce their fuel bills and increase the value of their homes.

Some politicians find this transfer of cash unsatisfactory - but experience suggest that if people are not given incentives, their homes will continue to require heavy heating and the government will miss its carbon targets.

Stability

Are rules the answer?

One measure by the coalition government would have obliged people expanding their homes to upgrade the efficiency of the whole house at the same time, to avoid increasing energy use overall.

This policy was scrapped after a newspaper campaigned against what it called a "conservatory tax" - although it wasn't a tax and didn't apply to conventional conservatories.

The UK has some of Europe's cheapest energy prices but some of the highest bills because homes are poorly insulated

Ideas for the future include adjusting Stamp Duty and mortgage lending rules to send financial signals to jolt home-owners and home-buyers to improve their properties.

Meanwhile, the long-awaited report from the Competition and Markets Authority will be expected to attempt to drive down energy prices further.

This will be welcomed by bill-payers, but lower bills will actually reduce the economic case for long-term insulation improvements.

A government spokesman told the BBC: "We acknowledge that a long-term framework (for insulation) requires a policy mix that supports stability and confidence in the market.

"We will be working with industry to carefully consider future policy options."

For people working in the industry, and for people living in cold homes like John in Hartlepool, that stability can't come fast enough.

Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin and Facebook

- Published26 November 2015

- Published16 July 2015

- Published9 February 2015

- Published25 February 2015