Bling below the waves: 'A submarine of my own'

- Published

"This is an ocean planet, it's all down there," says Graham Hawkes of DeepFlight

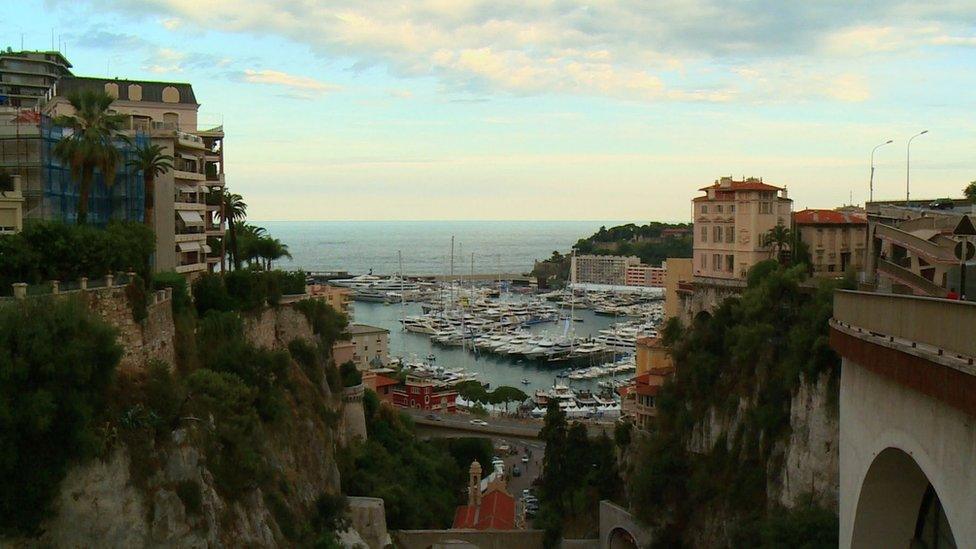

If you want to see how the truly rich spend their wealth, there are few better places to visit than the Monaco Yacht Show, held each year in late September.

The principality's vast harbour is littered with huge yachts belonging to those rich people who are not only proud of the trappings of their station in life, but are always looking for different ways to display it.

One story I heard was of a super yacht owner who had just found a new use for his vessel - the school run.

But for some, a mega yacht on its own is no longer enough - you need the latest accessories too. Amongst the newest of these is a machine whose time, advocates say, has come - the "personal" submarine.

For some of the super-rich owning a yacht is no longer enough

Several of the latest models were on display in Monaco, including some from a small US company - DeepFlight.

It was founded by the British engineer, inventor and entrepreneur Graham Hawkes, who has had an extraordinary career.

For many years he held a world record for solo depth diving; he's invented a robotic machine-gun; and he's played the part of a villain in a James Bond film. He designed and operated, external a small sub used in an underwater battle in the movie, For Your Eyes Only.

BBC presenter Peter Day and I first met Mr Hawkes in California several years ago. At the time he was obsessed with the idea of building a craft capable of going right to the bottom of the ocean.

Beaten to it by film director James Cameron, who accomplished the feat in 2012, he steered his business in a new direction.

Now, his company makes a range of submersible craft aimed at the super yacht crowd, marine researchers, and others.

One of the selling points of machines like these, says Mr Hawkes, is that they enable astonishing experiences.

Graham Hawkes says seeing the damage to the ocean close-up in a submarine could help people become more aware of the environment

Once, when he was taking the entrepreneur Sir Richard Branson on an underwater trip, they had a memorable encounter with a great white shark, which swam past them.

"It was bigger than this submersible", he recalls. "I was looking straight in to this eye of this huge predator and I was just in awe. And Richard was saying 'Graham, get closer, get closer'.

"And all I remember saying is 'Richard, I'm not going to lunge at a great white shark'. But we ended up laughing and giggling after that, we were so happy."

The devices made by DeepFlight differ from some other small subs because they are "positively buoyant," and need force or motion to keep them underwater.

If thrust disappears for any reason, the craft will float back to the surface - a feature which Mr Hawkes claims offers safety benefits.

The Super Falcon model works in a similar way to an aircraft, he explains: "It has 'wings' and you need to get some speed, about a walking speed on the surface, and then you point it down and the wings pull it down… and it flies under water. "

Advances in technology have helped to lower the costs of making small submarines

Another model, the Dragon, works more like a helicopter, and can "hover" underwater.

Small submarines have been around for many years but it is only comparatively recently that the market for them has begun to take off.

"My partner and I were at yacht shows twenty years ago with manned submersibles and bigger diesel electric luxury submarines," recalls another Monaco exhibitor, L. Bruce Jones of Florida-based Triton Submarines.

"And people would walk by our booth and sort of snicker at us - what are those crazy guys doing here?

"But now, fast forward twenty years and we're being accepted."

One reason for this change lies in recent advances in technology, which have helped to lower manufacturing costs, and also enabled the production of more versatile craft, with many additional features.

Personal submarines are now being designed with bigger windows so people get a much better view

Triton's range includes battery-powered subs that can dive down to depths of hundreds of metres for many hours before needing to return to the surface.

Another development, that is proving popular with customers, is the huge increase in the size of windows.

"In the old days you used to have this big steel pressure hull with small windows," says Erik Hasselman of Dutch sub makers U-Boat Worx, which is also exhibiting its products at the Monaco show.

Mr Hasselman says that recent improvements in acrylic technology mean that "we can build these very large acrylic spheres that will allow people to have a really big window," and thus get a much better view of what is happening beneath the waves.

Some tourist operators are already offering submarine trips

Prices for submarines start at $1.5m

None of this comes cheap. Prices for the smallest personal submersible craft start at around $1.5m (£1m). The high cost is likely to ensure that these products remain the preserve of the wealthy, commercial users, and well-funded research bodies.

However sub-makers also see the possibility of substantial growth in the leisure market, in which operators are already offering tourists underwater trips in small submarines.

If that happens, then increasing attention may start to be focused on the health of the world's oceans - something that many scientists are deeply concerned about.

At the moment, says Mr Hawkes, this issue can seem remote to many people.

But, he asks, "what if the politician …what if the fisherman, what if the housewife who was worried about the damage to the ocean could have gone and seen? … The important thing is that, [today] nobody can go, nobody can see.

"We're trying to change that."