'Fairness' of 2016 Budget under scrutiny

- Published

- comments

Fairness - a word as easy to shout about as it is difficult to define.

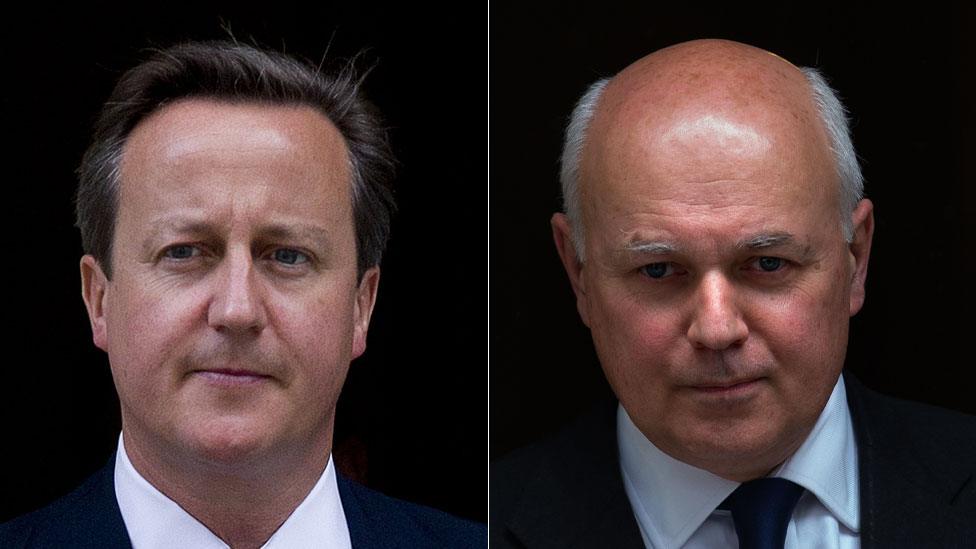

Iain Duncan Smith's resignation has put the issue at the heart of the government's approach to the economy - whether George Osborne's announcements in the Budget last week were "fair".

Mr Duncan Smith told the Andrew Marr programme on Sunday morning that the Budget was "deeply unfair", as it proposed restrictions to increases in the disability payments budget whilst at the same time provided an effective tax cut for those with higher incomes.

The first, Mr Duncan Smith suggested, was being used to fund the second.

Number crunching

To analyse the impact of the Budget on different income groups, economists turn to what is called a "distributional analysis" which aggregates the effect of tax and benefit changes.

By way of such an analysis, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) says that last week's Budget left the richest 10% of households about £260 a year better off.

The poorest 10%, the IFS says, were no better off and could actually see their net income fall slightly as benefits are reduced.

To understand the differential impact it is worth going back to the pledges made in the Conservative manifesto - to increase the personal allowance before those in work start paying income tax.

And second, to increase the threshold at which the higher 40p tax rate kicks in.

Both policies have a tendency to benefit the better off for two reasons.

If you earn under the new personal allowance announced in the Budget of £11,500 then the tax changes have no effect.

And you only receive the benefit of the increase in the 40p tax threshold if you earn more than £45,000.

Contradiction?

Using the IFS's model, many would say that the Budget was "unfair" in that the richest gained more than the poorest.

Which appears to contradict George Osborne's big point in the Spending Review way back in 2010 that those with "the broadest shoulders should bear the greatest burden".

But - the Treasury looks at distributional analysis in a radically different way.

Looking back to 2010, it argues that it is more revealing to consider the proportion of taxes paid and public services received.

On that basis, the top 20% of wealthy households will be paying 52% of all taxes by 2019-20, compared with 49% in 2010/11.

The amount of public spending they receive has remained static at about 11%.

As the IFS says: "The very highest earners - those on over £100,000 a year - have seen significant tax increases."

The Treasury analysis then goes on to argue that the lowest 20% of households will be paying about 6% of total taxes by 2019-20 - the same as 2010-11.

For that, they will receive 25% of all public spending, up a percentage point from 2010-11.

Those figures, the Treasury argues, show that despite the "pie" - the amount of government spending - being smaller the effects have been fairly distributed.

Disability payments

Whether you agree with the pounds and pence approach or the distribution of the pie approach, the argument about Budget "fairness" has also hung on the issue of the disability payments budget.

My Treasury sources tell me that this issue is more to do with controlling a ballooning budget than hitting an overall public spending surplus by 2020.

Digging through the Office for Budget Responsibility's analysis of the government's spending, the rising cost of the disability Personal Independence Payment (PIP) does stand out.

The OBR says that the cost of PIPs has risen by £1.4bn since its November forecast, and by £3bn since its June forecast.

The OBR makes it clear that the "transition from the Disability Living Allowance to PIP has saved less money than expected" and that average awards have been "revised up by 16% to £100 a week".

The government argues that it is "fair" to look at a budget that is rising so rapidly.

Critics say that disabled people are being targeted at the same time as tax cuts are helping higher income groups.

And pensions are being protected.

Real headache

Whatever the arguments, since the controversy of the Budget the government has agreed to delay any reforms, thereby abandoning plans to cut £1.3bn from disability benefits in 2019-20, the year Mr Osborne has pledged to produce a public spending surplus of £10.4bn.

Does that, as some have suggested, blow a "hole" in the Chancellor's economic plans for 2019-20?

Hardly. In that year alone the government is expected to spend a total of £810bn.

So, £1.3bn is, in macro-economic terms, small change.

A small revision upwards of economic growth projections or tax receipts would easily cover the costs.

Although, of course, those forecasts could go in the other direction - creating a real headache for the resident of Number 11.

My Treasury sources tell me that far from Mr Duncan Smith's former Department of Work and Pensions having to find that £1.3bn saving elsewhere from their budget, the whole issue will be looked at "in the round" at the time of the Autumn Statement towards the end of the year.

And by then, of course, we will know the outcome of the European Union referendum.

Which will put a whole different complexion on the state of the UK economy - for better or worse.

- Published21 March 2016

- Published11 March 2020

- Published16 March 2016