Why are America's suburbs getting poorer?

- Published

Poverty in the areas just outside US cities is rising faster than inside the urban centres

Cities have always been crowded places, but the number of urban residences is set to double by 2050 to 3.5 billion, according to the United Nations.

In the US, 63% of the population already lives in cities. While this puts a strain on urban infrastructure there is also a large population just outside city borders struggling every day.

Sisters Sonya Underwood and Tonya Pinkston are far too familiar with the issue.

In April, the housing stipends Ms Underwood used to pay for her home ended when she completed her course in aviation management.

Sonya Underwood (left) and Tonya Pinkston (third from left) with their children

She and her three children were forced to move in with Ms Pinkston, her daughter and the sisters' mother. The family of seven are now living in a two-bedroom house in Gwinnett County - part of Atlanta's northern suburb.

"We can't keep doing this," Ms Pinkston says of the family's living situation. "We need to find something else even if it's one of those extended stay motels."

Rising rents

But finding a place for the family is proving difficult. Ms Pinkston and the sisters' mother are both on disability benefits leaving Ms Underwood as the main earner for the family. Few places that they can afford are large enough to accommodate them all.

Even if the family split into two houses their options are limited.

Rents, even in the suburbs, are rising and many of the best rental homes in suburban Atlanta are owned by private equity firms.

Many of these firms swooped into the market during the recession, buying up foreclosed homes and fixing them up for renters. These houses are typically well-maintained, but come with higher monthly rents and higher credit requirements.

These are standards many in the region are struggling to meet. It's forced some to take up long-term residence in local motels that don't check credit and others to move several generations of a family into one home.

Poverty in Atlanta's suburbs has been rising

"The rent stretches your budget a lot and I know I'll have to travel for work," says Ms Underwood. The travel means she'll have to pay for a car and rely on her sister and mother for childcare while she's gone.

The sisters are resistant to moving to an even cheaper suburb - for example, to the south of Atlanta - because it would mean forcing their kids to change schools. All four children, including Ms Underwood's youngest who is autistic, have thrived in the Gwinnett school district.

But the family knows they are struggling more than their neighbours.

"We're just trying to acquire the basic necessities - a good clean place to live, a decent car to drive," says Ms Pinkston.

National problem

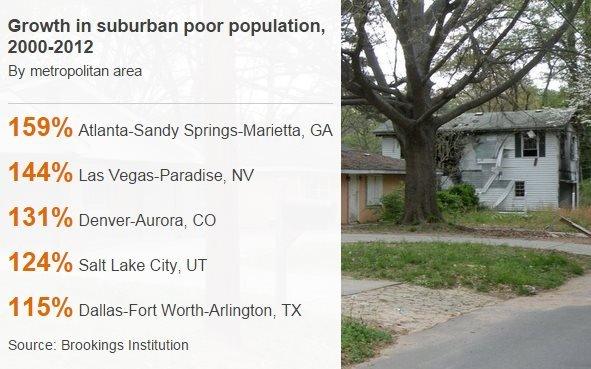

Atlanta has seen a big rise in suburban poverty. Between 2000 and 2012 the rate increased by 159% in Atlanta's suburbs.

But the region is not alone. For instance, in Denver the rate rose by 131% and in Portland by 98%.

In the US suburban poverty affects an estimated 16.4 million people and, if the current trend continues, could increase to 24.5 million by 2020.

That trend began before the financial crisis, but the recession exacerbated many of the problems and the recovery has not healed them.

"That rapid poverty growth in mid-to-late 2000s has levelled off, but we haven't seen improvement, we are still stuck," says Elizabeth Kneebone, a research fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Her research points to a number of factors, external - stagnating wages, a decrease in well-paid full-time jobs, lack of affordable housing and transportation, and poor education and training.

Even those who are above the poverty line are affected by the impact of living in a poor community, for example, by crime and underfunded schools.

Families that stretch their budgets to escape those neighbourhoods can find themselves trapped and possibly fall further into poverty.

America's suburbs were once wealthy havens for families fleeing crowed inner cities. Many people still think of them in this way

"Existing homeowners are underwater," says John O'Callaghan, president of Atlanta Neighbourhood Development Partnership. "They took hits to their credit to keep their homes and now they're stuck."

Mr O'Callaghan explains that this has created a housing shortage in the suburbs of Atlanta. Homeowners can't sell their houses because they would lose money. Most also cannot afford to make repairs and some are housing extended families who still can't afford places of their own.

The good Samaritan

In Atlanta's southern suburbs Nkrumah Moore is helping families in just this situation.

For the last eight years, he has been buying homes and giving them to homeless families rent-free for three to six months while they get back on their feet.

The homes typically cost around $20,000 (£15,500) and while he is fixing them up and preparing to rent them he allows locals who are struggling with poverty to live in them. Often he even gives them jobs in his handyman business, which fund his ability to buy these properties.

In Clayton County, where Mr Moore lives, per capita income in 2014 was $18,074, according to the US Census Bureau. It was $35,719 in Atlanta.

Nkrumah Moore often hires the people who move in to help with his handyman business, allowing them to earn extra cash

Mr Moore started letting out his homes for free during the recession when he saw so many empty homes and so many homeless people. He currently has seven houses.

"There are a lot of people struggling and there is nowhere for them to go," he says. "Shelters aren't designed for families and a lot of people lose their jobs because they can't get to them on the bus lines."

Need a ride

Poor transportation is a major issue for many poor suburban residents.

Some people travel for hours each day on several bus and train lines to get to work, while others may lose jobs entirely because they can't get there without a car.

Owning a car though adds another strain on many families' budgets. Mr O'Callaghan says many people think they are saving money by moving further out of the city, but the extra cost of transportation and time it takes them to reach jobs exacerbates the problem.

"It's a cycle they get trapped in," he says.

Most suburbs have poor public transportation making it hard for poorer people to get to work

Taking a job closer to home isn't always an option either.

"In the suburbs, there are more jobs in retail, manufacturing and construction that may not pay as well," says Ms Kneebone.

"In the early days of the economic recovery we were counting jobs, but it's clear that we need to look at what jobs, how good they are, how much they pay and where are they located."

None of these concerns are unique to the US.

Globally, as more people move into cities, others will be pushed out. And while the focus will be on city infrastructure for the billions of urban dwellers, suburban poverty will fester if those individuals are left isolated outside the city walls.

More from the BBC

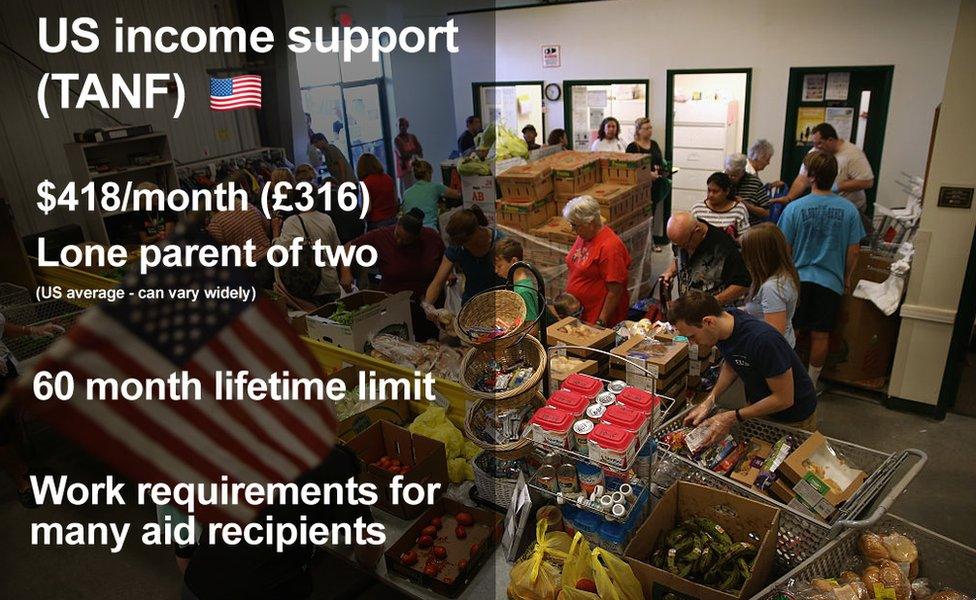

Twenty years ago, the US overhauled "welfare" - meaning direct cash assistance to poor families.

But how does this aid compare to income support programmes in other high-income countries?

- Published26 August 2016

- Published22 June 2016

- Published14 April 2016