Counterfeit drugs: 'People are dying every day'

- Published

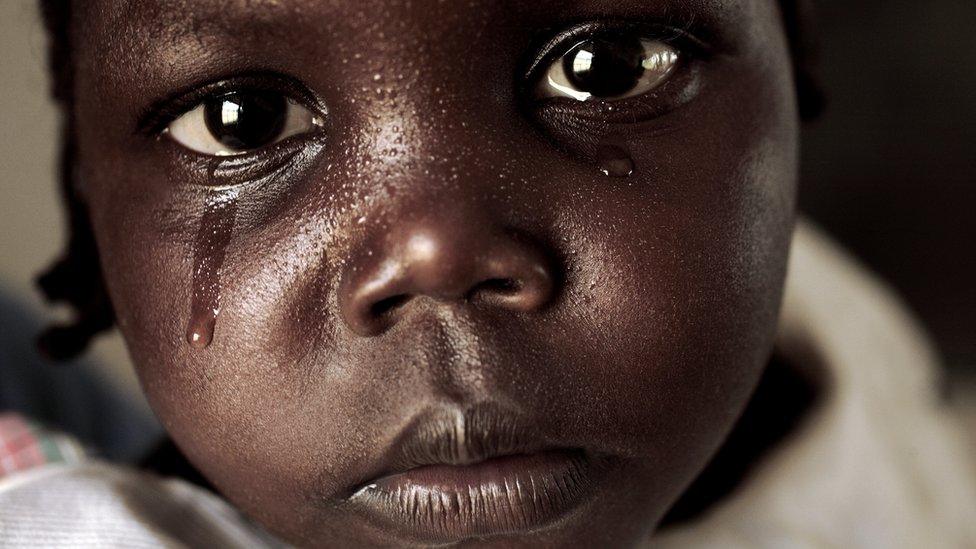

Children are very susceptible to malaria, so fake drugs can be a death sentence

Imagine seeing your child suffering from malaria, one of the biggest killers of children across the world. Symptoms include high fever, sweating, vomiting and convulsions.

But it's OK, you think, because you bought medicine to combat the disease from a local drugs market.

Now imagine what it must be like to see your child die nonetheless because the drugs you bought were fake.

That is the brutal reality of the multi-billion dollar a year global trade in counterfeit drugs.

More than 120,000 people a year die in Africa as a result of fake anti-malarial drugs alone, says the World Health Organization, either because the drugs were substandard or simply contained no active ingredients at all.

Even medicines that are substandard - containing an insufficient dosage of active ingredients, say - can be deadly, leading to drug resistance, a particular issue for infectious diseases like malaria and tuberculosis.

Fake and stolen drugs are often sold openly in street markets

By some estimates, about a third of all anti-malarial drugs in sub-Saharan Africa are fake. And these fakes can find their way into pharmacies, clinics and street vendor stalls, or be sold online via thousands of unregulated websites.

But a handful of start-ups have been trying to tackle the issue using technology.

'Simple and cheap'

One tech firm, Sproxil, offers a beguilingly simply solution.

Participating drugs companies apply for scratch-panel stickers that can be attached to their packets of drugs. Customers scratch off the panel to reveal a code which they text to Sproxil. The company checks the code against its database of genuine drugs and texts back a confirmation of authenticity.

Consumers scratch off a panel to reveal a unique code, then text this to Sproxil

Buyers can also scan the barcode or simply ring a call centre staffed 24 hours a day, seven days a week to verify that the drugs are genuine. And Sproxil has introduced incentives for consumers to use the service, such as mobile phone air time rewards.

More than 70 drugs companies have signed up to the service, including multinationals such as GlaxoSmitKline and Novartis, says Sproxil spokesman Tolulope Gbamolayun, and about 28 million verifications have taken place globally since the scheme was launched in 2009.

Sproxil boss Dr Ashifi Gogo believes his firm's system is saving lives

"It's a security measure that is simple and cheap," says Mr Gbamolayun.

In Africa, the scheme operates in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, and most recently, Mali.

"But we're trying to spread our tentacles across all the countries of Africa," he says.

Catching the fraudsters

Social entrepreneur Bright Simons set up a similar "verify-by-mobile" system called mPedigree Network nearly 10 years ago.

Printed barcodes and scratch-off stickers, developed in partnership with US tech giant Hewlett-Packard, help consumers check authenticity against a central database.

"But you need to be able to track the product at each stage of its journey from the factory to the consumer," Mr Simons tells the BBC. "The consumer app was easy to develop, but the back-end was much more difficult."

Consumers can text a unique code to mPedigree and find out if the product is genuine

He says mPedigree's Goldkeys product helps manufacturers and regulators "monitor the entire supply chain. In Nigeria, our technology has helped regulators pinpoint where fraud is happening and catch the fraudsters."

Bespoke software helps drugs manufacturers register each packet of medicine in the factory and incorporate this data into mPedigree's database, which has now registered more than 2,000 products.

Mr Simons estimates 75 million people have benefited as a result of fake drugs being intercepted in Africa, and mPedigree now operates in 12 countries across Asia and Africa.

'Invisible printing'

The pharmaceutical industry has applied a number of other technologies to the issue, including the use of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) tags.

"Our industry helps to prevent and detect fakes in the supply chain, namely through implementation of overt and covert technologies, including invisible printing to be applied on the actual packages, and forensic techniques such as hi-tech solutions that require laboratory testing or dedicated field test kits," says Mario Ottiglio, director of public affairs at the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA).

Big seizures of fake drugs only scratch the surface of the illegal trade

The United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), a body dedicated to setting drug quality standards, set up the Centre for Pharmaceutical Advancement and Training (CePAT) in Accra, Ghana.

CePAT aims to train African professionals how to screen for substandard and fake drugs, and since 2013, has helped train 190 professionals from 32 African countries, says USP chief executive Ronald Piervincenzi.

'People are dying'

But if such tech solutions are working, why are so many people still dying and suffering as a result of fake medicines?

"Most of the fake drugs are made in Asia and then imported into Africa," says Mr Simons. "The scale of the trade is huge and what we're doing is tiny compared to the size of the problem.

"And the very big multinational pharmaceutical companies have been very conservative - they've taken a long time to get on board," he says. "Tech start-ups can't solve the problem by themselves."

Bright Simons says corruption is a big problem in the fight against counterfeit drugs

Sproxil's Mr Gbamolayun agrees, saying: "We're trying to raise awareness and spread the good news to brand owners and customers around the world, but we need to educate a lot more people.

"Counterfeit drugs are still a big problem - people are dying every day."

Corruption is also to blame, says Mr Simons, with government ministers often purloining subsidised medicines and selling them privately at inflated prices, and inspectors accepting bribes to turn a blind eye to fake shipments.

"There's a black hole of accountability; we need far more transparency throughout the whole system," he says.

Some involved in the fight against counterfeit drugs have also complained about the comparatively light sentences for those prosecuted compared to the sentences given to criminals peddling narcotics.

"In countries with weak drug regulatory bodies that are poorly funded and poorly staffed, and where enforcement by the customs services and policy agencies is also weak, counterfeiters will continue to flourish and operate," warns IFPMA's Mr Ottiglio.

Technology can only do so much.