Can the UK take over existing EU trade agreements?

- Published

Building British trade outside the EU is a priority for Theresa May's government, so existing deals could be a useful starting point to any negotiation. But could the UK take over existing trade agreements the EU has with other countries, under "grandfather rights", the phrase for allowing old rules to continue to apply amidst new arrangements?

The short answer is it might be able to do just that.

We do not know that for sure. We are in uncharted waters. And there are some potential complications. But it could conceivably happen, especially as a temporary, transitional path towards a more permanent solution.

Here is the longer answer.

The European Union has 34 bilateral and regional trade agreements, external in place, which cover in total 60 partners.

The central point of these agreements is they make it easier for EU businesses to sell their goods to the other country (and vice versa).

Why Andrew wrote this article:

We asked readers to send BBC economics correspondent Andrew Walker questions on global trade.

Andrew selected four questions and you picked your favourite, which came from Rob Sadler.

Rob asked: "Why can't the UK just take over existing trade agreements that the EU has with other countries, under grandfather rights?"

He felt people were suggesting making trade deals following the the UK's exit from the EU would be an insurmountable problem.

"Surely when we leave the EU those countries that have trade deals with us would be happy to keep trading with the UK on the same terms? Why can't we just transfer the deals over to the UK?" Rob said.

"I can't imagine any country would want to drastically change their current arrangements."

There is some variation in exactly what goods these agreements cover, but for many exporters they mean they face no tariffs on their goods - taxes that countries slap on imports.

There are some important trade-partner countries that are covered by these agreements, including South Korea, South Africa and Mexico.

There is a complicated package of agreements with Switzerland.

There is also one with Canada , externalthat has been agreed but has not yet come into force (and it has become very controversial, external).

Some of the others are, let's say, not exactly global economic powerhouses: Andorra and San Marino for example.

Obvious incentive

These existing deals look like they could be a useful starting point.

Whether they would be or not depends first of all on the other countries.

If they think it is worth continuing the arrangement on existing terms, that deals with the first hurdle.

The UK is a large economy, one of Europe's largest. So, for many countries, there is an obvious incentive to do that.

But there could be complications, especially if as seems likely we end up outside the EU's customs union.

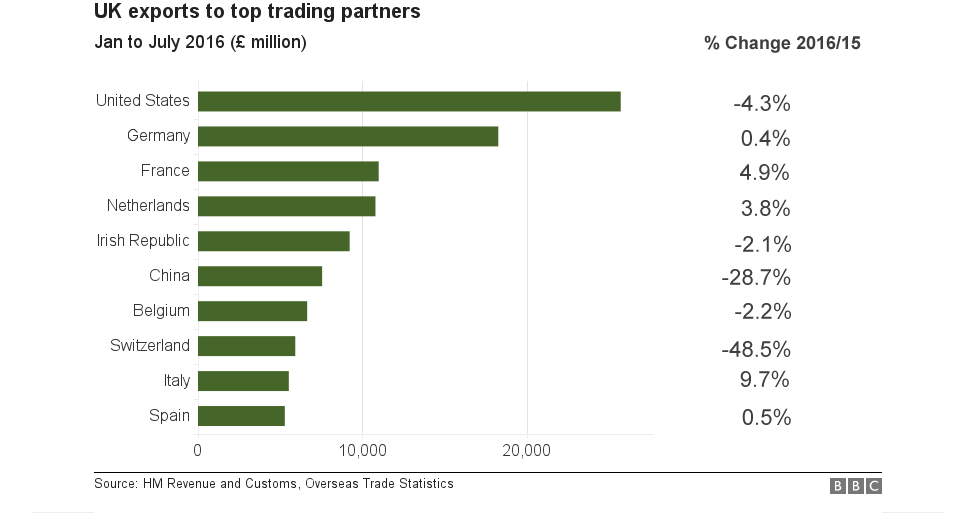

Switzerland is the biggest UK export destination that currently has a free trade agreement with the EU

Under these agreements, a certain percentage of a good's value has to be added in the exporting country.

With the EU you could have components made in France and Spain further processed in Germany and then made into a finished product in the UK and it would be covered.

But with a separate agreement for the UK post-Brexit, it probably would not be.

This is not insoluble, but it could require a time-consuming negotiation to deal with it.

In the other direction, something from Mexico, for example, arriving in the port of Lowestoft and clearing customs there can currently be shipped onwards anywhere in the EU.

That would no longer be true if the UK leaves the EU customs union.

So that would mean that two separate deals, one with the EU and one with the UK, might be a little less attractive to Mexico (for example) than the current single one.

Then there is the question of how the rest of the member countries in the World Trade Organization (WTO) would react.

If the UK and other countries were to simply continue allowing each other tariff-free market access without a formal new trade agreement, other WTO members might claim they should have the same.

The reason is that under WTO rules countries are generally supposed not to discriminate among trade partners, external.

There are exceptions though, including formal bilateral and regional trade agreements that have been notified to the WTO.

Without one, the UK might be on thin WTO ice.

But then if all this were simply a temporary arrangement while a proper agreement was being negotiated and it had not irritated WTO partners unduly over other issues, the UK "would probably get away with it", according to Prof Alan Winters, of the UK Trade Policy Observatory at Sussex University.

The legal agreements have the UK as a signatory as well as the EU and the other member states.

But Piet Eeckhout, a law professor at University College London, thinks we cannot assume they would therefore apply automatically to the UK post-Brexit.

The UK leaving would change fundamentally the nature of our agreement with the other country.

The conclusion? "Grandfathering" might work, but it is not automatic.

- Published5 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016

- Published6 October 2016