How the Big Bang changed the City of London for ever

- Published

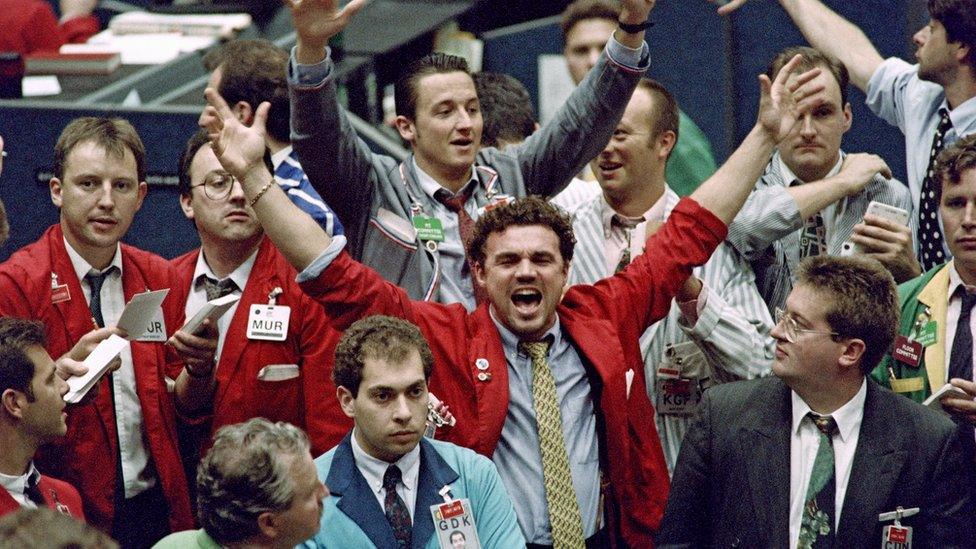

After Big Bang introduced electronic trading, the London exchange's trading floor became redundant

"I was used to the hustle and bustle, the crowd on the floor," says Alasdair Haynes.

"And on the Monday there was no one there. There was a complete hush, it was extraordinary," says Mr Haynes who used to work on the floor of the London Stock Exchange, and is now chief executive of the trading venue Aquis Exchange.

The Monday he's referring to was 30 years ago. It was the day of the Big Bang - when, in one fell swoop, the City of London was deregulated, revolutionising its fortunes and turning it into a financial capital to rival New York.

London's switch in 1986 from traditional face-to-face share dealing to electronic trading helped it outpace its European competitors and become a magnet for international banks.

Thirty years ago today the City changed for ever after radical new rules were introduced.

Even if London now loses access to the single market, many believe the Big Bang's legacy is a financial infrastructure with foundations too deep to be moved.

But many also say it sowed the seeds of the 2008 financial crisis.

There were three key elements to the Big Bang revolution:

Abolishing minimum fixed commissions on trades

Ending the separation between those who traded stocks and shares and those who advised investors

Allowing foreign firms to own UK brokers

British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher with her Chancellor Nigel Lawson (left) were the architects of Big Bang

By ending fixed commissions Big Bang allowed more competition; by ending the separation of dealers and advisors it allowed mergers and take-overs; and by allowing in foreign owners it opened London's market to international banks.

Coupled with the new magic of electronic trading, the City jumped from the 19th Century to the threshold of the 21st.

Changing world

It is generally thought that Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister drove through Big Bang as part of a programme of deregulation, but there were already powerful forces at work.

By the early 1980s the competition authorities were threatening to take the stock exchange to the Restrictive Practices Court.

Nicholas Goodison, then chairman of the Stock Exchange, believed it would be better to pre-empt the lawyers and avoid being forced to tear up its rule book.

In any case the world was already changing. The US had abolished fixed commissions in 1974, and in 1979 the Conservative government abolished exchange controls - triggering for many the UK's financial and economic rebirth.

The old stock exchange at Capel Court, where "waiters" watered the floor to keep down the dust

"And there were other developments," says David Buik, now a market commentator at Panmure Gordon.

"You have to remember that LIFFE (the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange) had started up in 1982 and already attracted the big American and Japanese banks - not to mention the privatisations of British Gas, British Airways and so on."

In the end it was Mr Goodison, Trade and Industry Secretary Cecil Parkinson, and Chancellor Nigel Lawson, who persuaded Mrs Thatcher to back the reforms that changed the City for ever.

Jobbers and brokers

City traders were then strictly divided into two; jobbers and brokers. Brokers liaised with clients and then gave their orders to jobbers who did the actual trading, face-to-face in "open outcry", on the exchange floor.

For years, trading was done at the old Capel Court exchange, known as The House, where "waiters" would water the floors with watering cans to keep down the dust.

LIFFE, London's financial futures exchange, was the first in the City to attract foreign investment banks

Nowadays the pre-Big Bang City has a bowler hat image, where a good lunch and long friendships were more important than profit. But it wasn't all like that, according to Brian Winterflood, later the founder of Winterflood Securities, who had been a jobber at Greener Dreyfus since the 1950s.

"We had lunch but we never stopped trading," he said in a 1990 interview. "If we were too busy for lunch we wouldn't go to lunch, and you'd snatch a half an hour now and again."

Trading boom

Crucially for the subsequent development of London as an international financial centre, the Big Bang produced a free-for-all, as brokers, jobbers and the City's traditional merchant banks merged.

Some were bought by UK clearing banks but many more were snapped up by much bigger US, European and Japanese banks.

The 300 member firms of the stock exchange had all been domestic - but within a year 75 were foreign-owned. With this came electronic trading, cutting costs as the competition increased. The jobbers vanished and the trading floor became deserted.

All this meant that the volume of trade that flooded through the new terminals soared, averaging more than $7.4bn a week after Big Bang compared with $4.5bn a week beforehand.

And costs also came down.

"When I started out it cost a fortune to trade, the spreads between buying and selling were huge. Now you can trade on your mobile phone for a fiver," says Mr Haynes.

It is said that Big Bang created 1,500 millionaires. Some 95% of the firms had been owned by partnerships, and dazzled by the massive sums on offer many sold up and retired.

A Canary Wharf advert promised it would "feel like Venice and work like New York"

It also changed the geography of London. Until then the Bank of England had insisted that all of London's banks had to be within 10 minutes' walking distance of the governor's office so, it was said, in a crisis he could summon the lords of finance to his parlour with half an hour's notice.

But the Securities and Investments Board (later the Financial Services Authority) replaced the Bank's regulatory role.

On the day of Big Bang an advertisement in the Financial Times promised a new financial centre, three miles to the east of the City at Canary Wharf, which would "feel like Venice and work like New York".

Changing attitudes

Yet not everything went to plan. In the short term there was a problem of massive overcapacity. The banks found they had overspent.

The following years saw them closing down venerable firms like Vickers da Costa, Scrimgeour Kemp-Gee, Fielding Newson-Smith, Wood Mackenzie; names that now appear only in history books and at the bottom of senior financiers' resumes.

By 1992 Canary Wharf was forced into bankruptcy as it struggled to find tenants.

But in the 1990s and 2000s, profits, salaries and bonuses boomed. Even Canary Wharf recovered and thrived.

The City of London's trading culture has changed radically in 30 years

The result was a financial sector many believe is Brexit-proof. "The banks built a huge infrastructure in technology, transport, education and telecoms, and that infrastructure is unique," says Mr Haynes.

"People who say we are going to move off to Paris or Frankfurt don't understand you can't build an infrastructure like that overnight. It can't be rebuilt quickly just anywhere in the world."

But with the wealth came something more ambiguous, and dangerous - a change of attitude. "It became much more of a dog-eat-dog environment," says David Buik.

"In the old days you would have been very careful to look after your client, you had a relationship. But it became a competition on rate and pricing. And the earnings became colossal."

Much of this was based around a bonus culture which rewarded the best deal, while short-term trumped long-term.

Some people understood better than others what was happening.

David Willetts, later a Conservative minister, warned of the potential dangers of Big Bang

David Willetts, who was then working in the No 10 policy unit but went on to be a Conservative minister, co-authored a paper for Mrs Thatcher on the likely impact of the Big Bang.

He expressed concern about "unethical behaviour" and that financial deregulation could lead to "boom and bust" But he concluded while there might be "individual financial failures" he did not expect "a systemic problem".

On this he was wrong. The 2008 financial collapse was systemic. It prompted a new wave a regulation, trimming some of the City's freedoms.

However, no one, save perhaps the odd elderly broker, dozing now in his Surrey mansion, would dream of returning to the days of bowler hats when the waiters watered the floors in Capel Court.

Correction 24 January 2017: An earlier version of this story incorrectly said the Capel Court Stock Exchange closed in 1967 - this referred to a temporary shutdown.

- Published26 July 2016

- Published4 February 2013