Be more squirrel: How to save £60,000 by the age of 40

- Published

It would be the perfect nest egg, and certainly enough for a deposit on your first house or flat.

Yet for most people, saving £60,000 looks to be well out of reach.

Indeed, as the BBC reported last month, 16 million people in the UK have savings of less than £100. In many parts of the country, such people are in the majority.

Some of those on low incomes say they do not earn enough to save anything.

But now campaigners are out to persuade them that the task of saving tens of thousands of pounds does not have to be as hard as one of the labours of Hercules.

It is, actually, achievable.

Budgeting

One such campaigner is Robert Gardner, chair of the Children's Savings Policy Council, and author of a new children's book called Save Your Acorns.

In the story, the monkeys eat up all the bananas they possess.

The bears eat most of their berries, and store up those left over.

But the squirrels do something different entirely. Before eating any of their acorns, they save 20% of them, and learn to live on those that remain.

Those saved acorns grow into oak trees, with more acorns.

"The point is that saving doesn't mean you can't enjoy things in life," says Mr Gardner.

"But it's about budgeting. You get 10 and bank two. That two is what will help you in the future."

Robert Gardner believes most people can save tens of thousands of pounds

So how does this acorn philosophy work in practice?

Stop buying, for example, one cup of takeaway coffee every day, he recommends.

Save that £2.50, and invest it in the government's new Lifetime Isa, which is due to launch in April 2017.

If you invest it in shares, rather than cash, it could grow by as much as 7% a year.

The government will also add 25% to each annual investment you make.

You might also like:

Taking into account the effects of compound interest, if you keep up the savings every day between the ages of 18 and 40, you could end up with as much as £60,000, he claims.

The only catch is that you would have to spend that money on a house or flat, or save it until you are 60. Otherwise, according to the rules of the Lifetime Isa, you would forfeit the government bonus.

'I saved £2,000'

But even without the benefits of the Lifetime Isa, some people on low incomes have still managed to save large amounts.

Alison Schofield from Halifax in West Yorkshire was on a salary of less than £16,000 a year.

Alison Schofield managed to save £2,000

As a result of a disability known as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, she was also entitled to some benefits.

Nevertheless, after taking part in a savings challenge organised by the government-backed Money Advice Service, she managed to save between £200 and £300 a month.

At one point she had £2,000 in an Individual Savings Account (Isa).

"It takes a lot of worry out of your life," says Alison.

"It gives you nice things to spend money on, and you sleep better as well."

One way she managed it was by making herself a sandwich every day for lunch, instead of buying one - so saving £3 a day.

"You just make it a habit when you get in at teatime - you put the £3 in the tub."

How Alison did it

Apart from saving £3 a day, Alison kept spreadsheets on her computer to track her income and her outgoings.

Alison switched to using cheaper supermarkets, like B&M in Halifax

She also:

prioritised her debts, paying off the most expensive first

switched savings accounts, "just to get a little snitch more"

switched supermarkets, saving up to £25 a week on food

put money away in advance to cover bills

reduced the spending limits on her credit cards

put thermal lining behind her blinds to cut heating bills

If all that sounds like hard work, there is a new way of saving that involves doing precisely nothing.

Savings apps

Mobile phone tools, similar to apps, can now work out when you've got a couple of pounds spare in your current account, and automatically switch them into a savings account.

Both Chip, external and Plum, external, as they're called, work as so-called bots on Facebook Messenger. In other words, users think they are having a conversation with a person, even though they are automated programmes.

Chip users can see how much money they're saving via their phones

The bots use algorithms that analyse your spending patterns, compare them with forthcoming income, and calculate what cash you don't need.

They then move that sum - possibly as little as £10 a month - into an account that pays interest.

"We wanted something that would take decision-making out of people's hands and automate it," says Plum's co-founder Victor Trokoudes.

"I love it when people say they can't save, because everyone can save. It's money coming out of your account in small amounts. But over time it accumulates."

Savings challenge

However, experts at the Money Advice Service (MAS) think it can be more fruitful to engage positively with saving, for example by setting a particular goal.

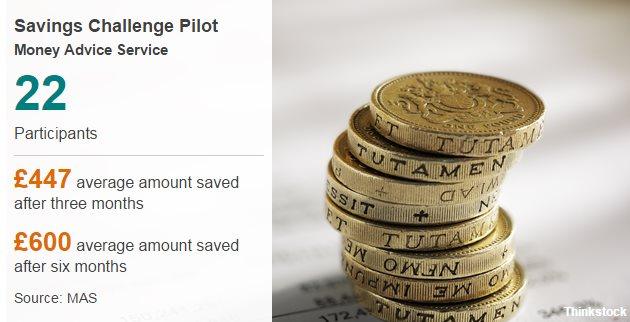

As part of its savings challenge pilot scheme, MAS asked 22 people - including Alison Schofield - to try to save £100 a month for three months.

It was left up to them to decide how they were going to do it.

On average, those who took part managed to save £447 over the three months. After six months, although one or two were derailed by leaking roofs or ill pets, the average amount saved was still over £600.

"The thing that motivated people - almost without exception - was the challenge," says Paul Taylor, head of digital at MAS.

"It was fun. And six months down the line there was a sense of automation."

Money Advice Service planning toolkit

Budget planner - click here, external

Quick cash finder - click here, external

How to save money on household bills - click here, external

In its guidance, MAS recommends that savers consider four "S" words:

Swap - buy a similar product at a lower price, even if it's of lesser quality

Switch - change tariffs for broadband, mobile phone, mortgage or energy

Sell - is there anything in the attic you could get rid of?

Start - begin a new behaviour, such as walking instead of taking the bus, or buying less food. (The average household wastes £40 a month, external on food that is thrown away)

"The key thing is just to give something a go," says Nick Hill, money expert at MAS.

"Start getting that momentum happening. It's amazing what small tweaks people can make to really start building up those savings."

In other words, be less like a monkey, and more like a squirrel.