The Body Shop: What went wrong?

- Published

Balmy days: The Body Shop story

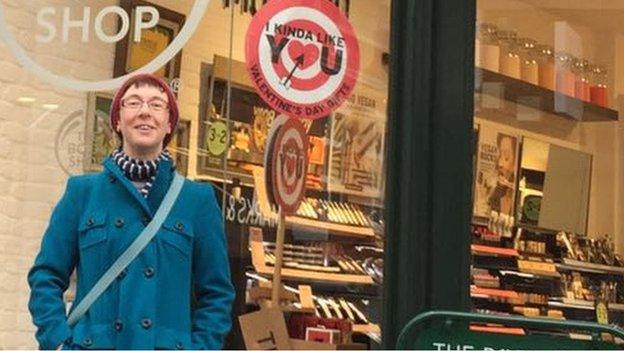

"A confused shop with a mish-mash of products with no emphasis on the fact that this is supposed to be a shop specialising in cruelty-free, fair trade toiletries and make-up," is Suzy Bourke's damning verdict on The Body Shop.

The 42-year-old stage manager used to be a regular shopper at the High Street chain, but now she tends to go to Boots instead.

And she's not alone. Its owner, cosmetics giant L'Oreal, wants to offload the High Street chain, which has been suffering slowing sales.

The Body Shop, founded by Dame Anita Roddick in 1976, was a pioneer using natural ingredients for its beauty products when it started out. It initially thrived, expanding rapidly, and by the 1980s was one of the most well-known brands on the High Street.

I remember the chain fondly from my youth, when it seemed to be an exciting shop full of affordable, fun and exciting products. Coloured animal soaps, banana shampoo, white musk perfume and strawberry shower gel were the height of 1980s beauty chic as far as I was concerned.

But by the early 2000s, rivals had caught up, with firms such as Boots, for example, developing similar natural beauty ranges. New challengers such as Lush also emerged, encroaching on The Body Shop's market share.

"You never see a Body Shop busy any more, they always used to be packed," says Suzy Bourke

The chain is still a sizeable High Street presence with more than 3,000 stores in 66 countries and employs 22,000 people, according to its website.

The Body Shop's results for 2016 show total sales were 920.8m euros (£783.8m), down from 967.2m euros in 2015, which L'Oreal blamed on market slowdowns in Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia.

The sales were a tiny proportion of L'Oreal's overall 25.8bn euros of sales for the same period.

And arguably the chain - which L'Oreal bought for £652m ($1.14bn) in 2006 - remains a lower-end and insignificant part of its huge portfolio of brands, which include skincare specialists Kiehl's, Lancome and Garnier, as well as fragrance brands Ralph Lauren and Giorgio Armani.

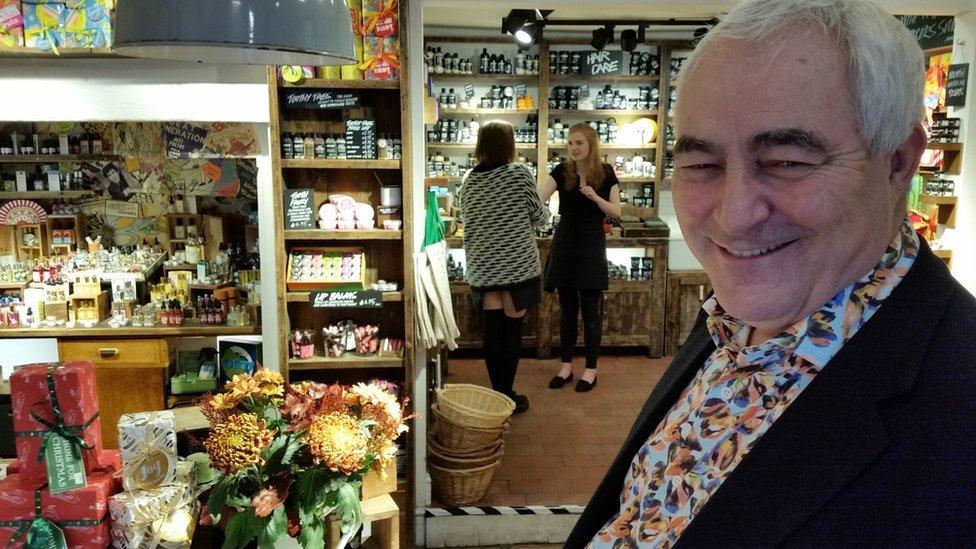

Veteran retail analyst Richard Hyman argues that L'Oreal overpaid for the chain and has failed to add any value to it.

"Frankly it's a bit of mystery them buying it in the first place.

"What they bought is a retailer and what they're good at is brands," he says.

The Body Shop's use of natural ingredients made it a pioneer when it started out in 1976

He thinks The Body Shop's struggles are down to the same issues facing the retail sector as a whole:

competition from an ever-increasing number of shops all muscling in on the same territory, from supermarkets to fashion chains

the seemingly unstoppable popularity of online shopping

the high cost of running a large number of shops

"Retailing in shops is becoming an increasingly challenging business. You've got to have a very compelling retail proposition as opposed to a brand or product proposition.

"Everyone that shops in The Body Shop spends most of their personal care budget somewhere else. They're constantly chasing their tail, having to work hard to attract people into a store," he says.

When the 2006 deal was struck, founder Dame Anita - who died just a year later - was forced to reject claims that The Body Shop, known for its ethically sourced goods, was joining with "the enemy".

There were concerns that some of the ingredients L'Oreal then used in its products had been tested on animals, while The Body Shop was publicly opposed to animal testing.

The French firm insisted the brand would complement its existing offering, giving it increased presence in the "masstige" sector - mass market combined with prestige.

But Charlotte Pearce, an analyst at consultancy GlobalData Retail, believes the firm has "slightly lost its way" under L'Oreal's ownership.

"While The Body Shop's heritage is strong, it needs to work on its brand perception. It's not known as a brand which is innovative and new, and it's failed to keep up with market trends - contour sticks, kits and palettes were a strong trend in 2016, and these are nowhere to be seen in The Body Shop's range," she says.

Analysts say The Body Shop has lost its cachet as a fashionable brand

These days the firm is not seen as "a trendy brand", but mostly as a shop for gifting and low-value items, such as its body butters and body lotions, she says.

"With premium retailers such as Jo Malone and Liz Earle offering in-store treatments, there is more that The Body Shop could be doing to raise its profile and improve the customer experience," she adds.

Nonetheless, Prof John Colley from Warwick Business School believes there will still be plenty of interest from private equity funds.

He expects the firm to be sold with its current separate management team, who he says are likely to have their own ideas for how to improve it.

"When a major corporate has decided it doesn't want a business, it will sell it, probably, whatever the price.

"They [L'Oreal] are trying to get rid of it because it's underperforming. But anyone bidding will see a clear turnaround. Independent ownership would probably serve the firm well. A refreshed image would almost certainly work," he says.

Mr Hyman, too, believes a new owner could improve The Body Shop, particularly by selling the chain's products outside its own shops. But he says trying to offload the large store estate with long committed leases will be a hindrance to any buyer.

"That's not to say it isn't a business with potential, but it could perform much more strongly," he says.

The Body Shop's ethical foundations

Dame Anita Roddick, who founded the firm in 1976 at the age of 34, said her original motivation, external for the firm was simply to make a living for herself and her two daughters while her husband was away travelling.

But as someone who had travelled widely, she set out to do things differently, relying on natural ingredients and her customers' interest in the environment.

"Why waste a container when you can refill it? And why buy more of something than you can use? We behaved as she [my mother] did in the Second World War, we reused everything, we refilled everything and we recycled all we could.

"The foundation of The Body Shop's environmental activism was born out of ideas like these," she wrote.

- Published7 December 2015

- Published3 February 2017