How crafts workers are learning to sell their work

- Published

Theresa Nguyen says she's learnt how to build closer relationships with her clients

One of the pieces that silversmith Theresa Nguyen is most proud of is called A Fair Wind. The work, made from silver and driftwood, is currently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

"I created it in honour of my family's escape from Vietnam," she explains.

A Fair Wind is on display at the V&A Museum in London

One night in April 1984, her family, together with dozens of others, crammed into her grandfather's fishing boat, and set sail across the South China Sea.

After many adventures, including a dramatic rescue by the captain and crew of a British oil tanker, the family eventually ended up in Wales, where Ms Nguyen was born.

Her own life may have been rather less exciting than that of her family, but nevertheless she has faced challenges. She studied jewellery making and silversmithing at Birmingham Jewellery School, and then went about setting herself up as a silversmith.

She was lucky enough to find a workshop in Birmingham's Jewellery Quarter where she could share a space with established craftsmen.

But she soon realised that having the right craft skills on its own was not enough; the business side of her work would also need attention. "Creativity is something that I'm really passionate about, but you do need to have both sides of the equation to survive," she says.

Skills shortages could hamper the future of bespoke crafted watches such as these

In recent years, the luxury industry across Europe has become concerned about skills shortages in certain disciplines. It has taken steps to improve matters, with companies like LVMH and Mulberry backing apprenticeship schemes.

More from the Life of Luxury series:

But acquiring the know-how to make luxurious items is only one part of the story. What about learning to sell them?

"The problem is the emphasis has all been on how good one could get at one's chosen craft," explains Guy Salter, the founder and chairman of Crafted, a mentorship scheme backed by British luxury association Walpole, which pairs promising artisans with industry experts.

"The idea of how do you run it as a business, how do you pay the mortgage, how do you even pay the rent on your workshop, has been neglected almost entirely," he adds.

Part of the answer, Mr Salter believes, lies in more training - but this time, looking at the business aspects of artisanship.

Being a "fluffy maker creative-type person" isn't enough to succeed, says Rebecca Struthers

Husband and wife team Craig and Rebecca Struthers make high-end watches and jewellery. Like Theresa Nguyen, whose workshop is near theirs in Birmingham, they are participants in the Walpole Crafted initiative.

"We knew absolutely nothing about business when we started out.

"When you're this fluffy maker creative-type person you think that everyone's your friend and going to help you out and it's not quite that way in the real world, so you have to toughen up quite quickly," says Mrs Struthers.

The couple say they have found great value in the scheme. "Getting advice from other business people is priceless," says Mrs Struthers.

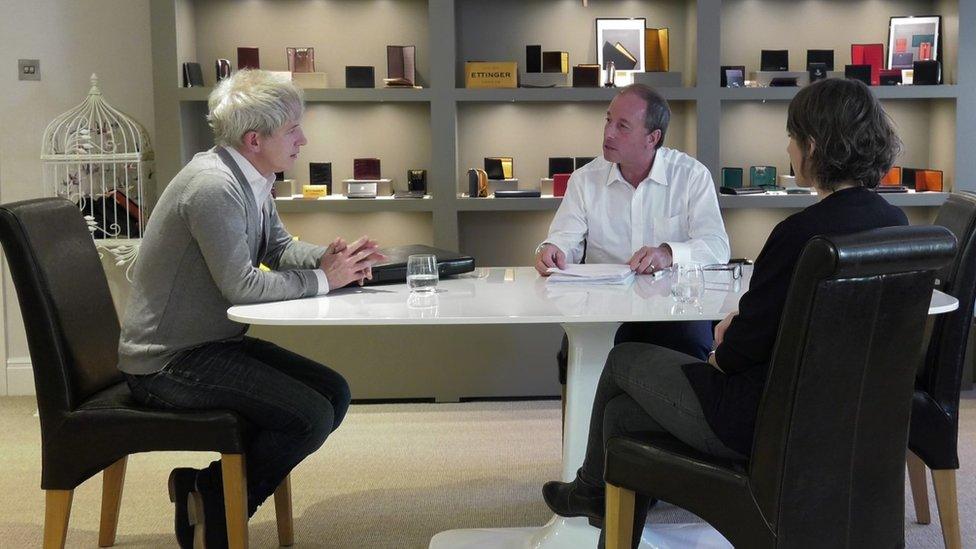

Robert Ettinger (centre) mentors husband and wife team Craig and Rebecca Struthers

The duo's mentor is Robert Ettinger, who runs a family business making leather goods.

He says one issue he frequently encounters with mentees is low sales volumes. He says this is a particular challenge for the Struthers. "They're selling very high-end price products so the number of customers that they can sell to is very small."

For Mr Ettinger, success depends on the artisans putting real time and effort into marketing. "It's always about bringing in business, finding the customers," he says.

Other experts agree that encouraging crafts workers to adopt a more business-like approach is sensible - but advice should be carefully thought out.

While learning about business is important, crafts workers shouldn't neglect their art, says Peter York

"It's a tricky balancing act," says Peter York, who has advised many large luxury enterprises. He says that crafts workers who lack basic commercial knowledge will "fail very quickly" unless they have the right help or can teach themselves the necessary skills.

But he warns that any advice should not go too far. "If you teach them all the [business school] stuff they'll want to be brands."

The danger then, Mr York continues, is that artisans may be tempted to concentrate too much on building a business, and hire others to carry out the actual making of products.

"Don't turn their heads so that they stop practising their craft," Mr York advises.

Things don't always go according to plan for artisans who are starting out. "Sometimes it's better if they don't always know the path ahead," says Jo Newton, head of buying for fashion, beauty and home at Fortnum & Mason, and also Theresa Nguyen's mentor.

Ms Newton says it is important for mentors to strike a balance between offering realistic advice, and encouragement. But, she adds, even if things do end up going awry "sometimes a failure isn't a bad thing", since it can offer an opportunity for learning.

She has found that those who can pick themselves up and start again often end up doing very well in the long run.

Theresa Nguyen says she has had to develop her business skills as well as her craft ones in order to succeed

So what lessons have the Walpole Crafted mentees learnt from their mentors?

For Craig and Rebecca Struthers, one valuable insight has been about pricing, particularly with high-end products, where there can sometimes be a temptation to set prices too low. "You don't think about what your individual skills are and your time, and why you're different," says Mr Struthers.

Another valuable lesson, says Mrs Struthers, has been learning to focus on work that will produce at least some sort of return.

"Being creative and being a business person are not things that gel very easily. It's easy to get carried away doing things that you want to do. But at the same time it's completely economically unviable," she says.

For Theresa Nguyen, a key lesson has been to build closer relationships with customers. "It's absolutely essential to the survival of your business because in getting to know the clients, that absolutely feeds into the work that you do."

- Published7 February 2017

- Published31 January 2017

- Published24 January 2017

- Published17 January 2017

- Published10 January 2017

- Published15 March 2016

- Published8 March 2016