Tick tock: The importance of knowing the right time

- Published

In 1845, a curious feature was added to the clock on St John's Church in Exeter: another minute hand, running 14 minutes faster than the original.

This was, as Trewman's Exeter Flying Post explained, "a matter of great public convenience", for it meant the clock exhibited, as well as the correct time at Exeter, "railway time".

Our sense of time has always been defined by planetary motion. We talked of "days" and "years" long before we knew the Earth rotated on its axis and orbited the Sun.

The Moon's waxing and waning gave us the idea of a month. The Sun's passage across the sky gave us "midday" and "high noon". Exactly when the Sun reaches its highest point depends, of course, on where you are.

Someone in Exeter will see it 14 minutes after someone in London.

Naturally people tended to set their clocks by their local celestial observations. That is fine if you co-ordinate only with locals. If we both live in Exeter and agree to meet at 19:00, it hardly matters that it is 19:14 in London, 200 miles away.

But as soon as a train connects Exeter and London - stopping at multiple other towns, all with their own time - we face a logistical nightmare.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Early British train timetables valiantly informed travellers that "London time is about four minutes earlier than Reading time, seven and a half minutes before Cirencester", and so on, but many passengers were understandably confused.

More seriously, so were drivers and signalling staff, increasing the risk of collisions.

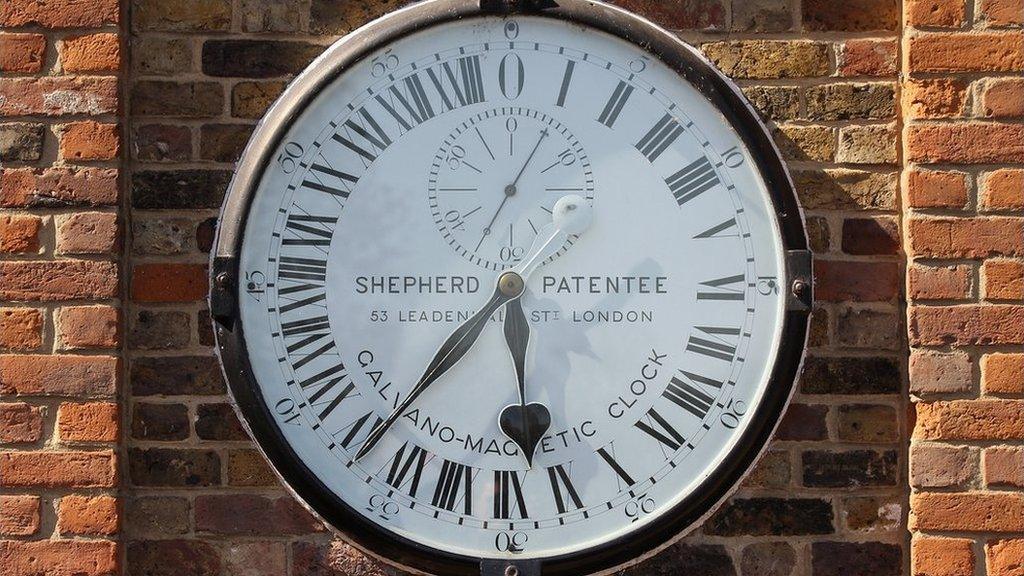

So railways adopted "railway time", based on Greenwich Mean Time, set by the famous observatory.

Railway companies such as GWR took accurate timekeeping extremely seriously

Some municipal authorities quickly grasped the usefulness of standardised national time.

Others resented this metropolitan imposition, insisting that their time was - as the Flying Post put it, with charming parochialism - "the correct time".

For years, the dean of Exeter refused to adjust the clock on the city's cathedral.

In fact, there is no such thing as "the correct time".

Like the value of money, it's a convention that derives its usefulness from widespread acceptance by others.

The longitude problem

But there is such a thing as accurate timekeeping. That dates from 1656, and a Dutchman named Christiaan Huygens.

There were clocks before Huygens, of course.

Water clocks appear in civilisations from ancient Egypt to medieval Persia. Others kept time from marks on candles. But even the most accurate devices might wander by 15 minutes a day. This didn't matter to a monk wanting to know when to pray.

But there was one increasingly important area of life where the inability to keep accurate time was of huge economic significance: sailing.

More from Tim Harford

By observing the angle of the Sun, sailors could calculate their latitude - where they were from north to south. But their longitude - where they were from east to west - had to be guessed.

Mistakes could - and frequently did - lead to ships hitting land hundreds of miles away from where navigators thought they were, sometimes disastrously.

How could accurate timekeeping help? If you knew when it was midday at Greenwich Observatory - or any other reference point - you could observe the Sun, calculate the time difference, and work out the distance.

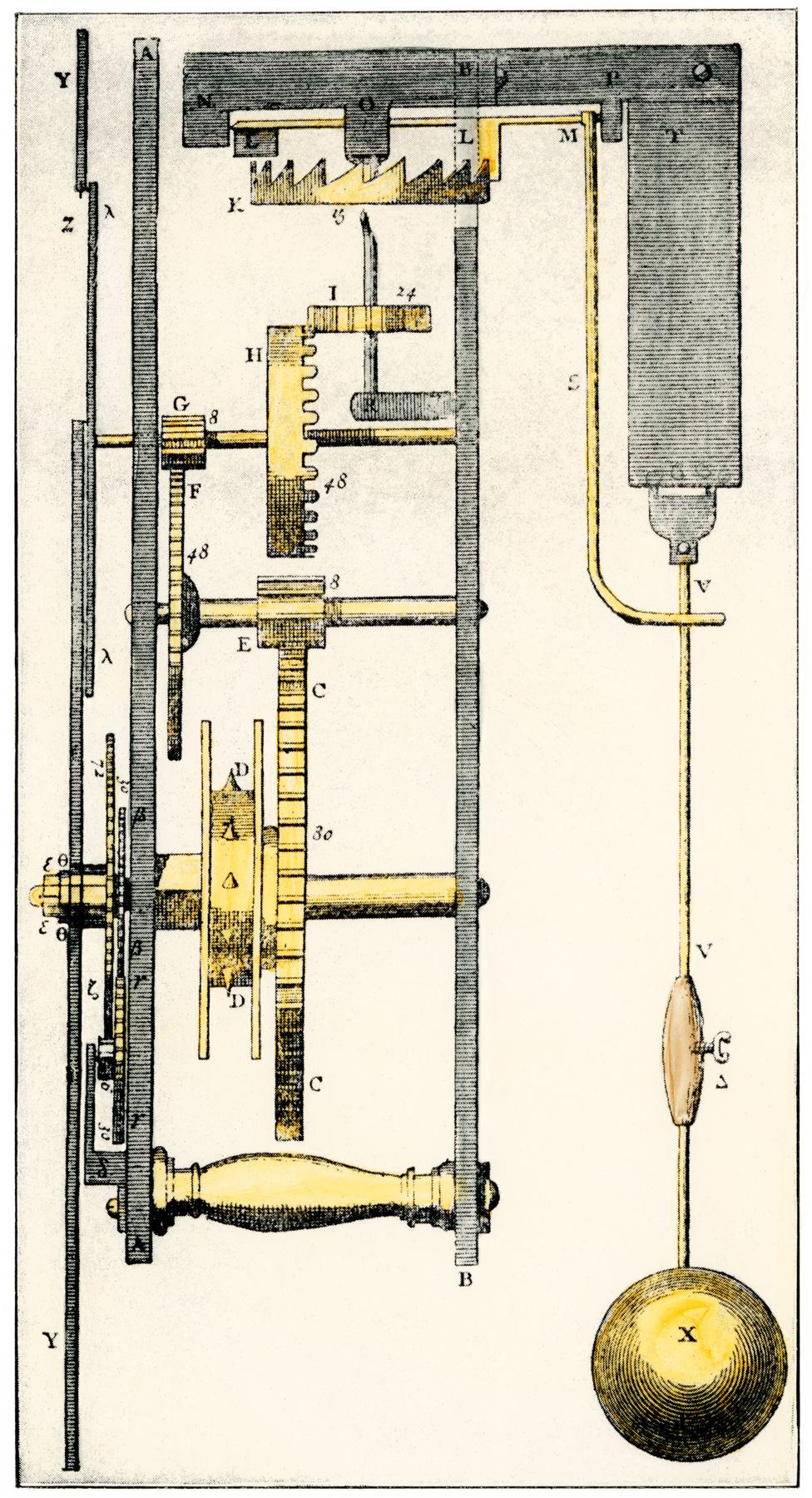

Huygens's pendulum clock was 60 times more accurate than any previous device, but even 15 seconds a day soon mounts up on long sea voyages. Pendulums don't swing neatly on the deck of a lurching ship.

Huygens's pendulum clock was 60 times more accurate than any previous device, but still lost time

Rulers of maritime nations were acutely aware of the longitude problem: the King of Spain offered a prize for solving it nearly a century before Huygens's work.

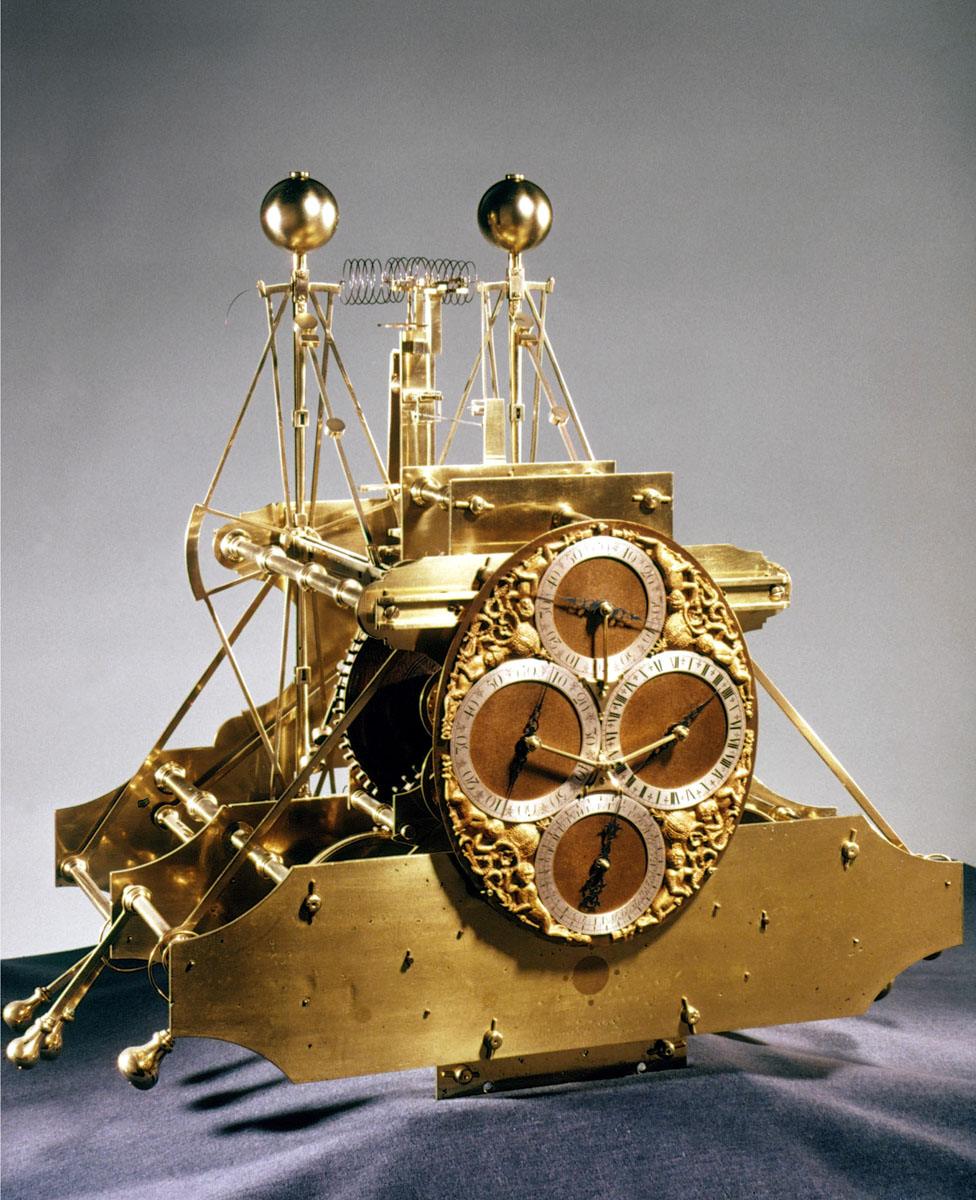

Famously, it was a subsequent prize offered by the British government that led to a sufficiently accurate device being painstakingly refined, in the 1700s, by the Englishman John Harrison. It lost only a couple of seconds a day.

John Harrison's Marine Timekeeper No 1 solved the longitude problem

Since the dean of Exeter's intransigence, the whole world has agreed on "the correct time" - coordinated universal time (UTC), as mediated by various global time zones.

Usually, these zones maintain the convention of midday being vaguely near the Sun's highest point. But not always.

Since Chairman Mao abolished China's five time zones and put everyone on Beijing time, residents of westerly Tibet and Xinjiang have heard their clocks strike 12 not long after sunrise.

Why milliseconds matter

Meanwhile, since Huygens and Harrison, clocks have become much more accurate still. UTC is based on atomic clocks, which measure oscillations in the energy levels of electrons, and are accurate to within a second every hundred million years.

Does such accuracy have a point? We don't plan our morning commutes to the millisecond, and an accurate wristwatch has always been as much about prestige as practicality.

For over a century, before the hourly beeps of early radio broadcasts, members of the Belville family made a living in London by collecting the time from Greenwich every morning and selling it around the city, for a modest fee.

Their clients were mostly tradesfolk in the horology business, for whom aligning their wares with Greenwich was a matter of professional pride.

But there are places where milliseconds do matter. One is the stock market, where fortunes can be won by exploiting an arbitrage opportunity an instant before your competitors.

Some financiers recently calculated it was worth spending $300m (£247m) drilling through mountains between Chicago and New York to lay fibre-optic cables in a slightly straighter line. That sped up communication between the two cities' exchanges by three milliseconds.

The accurate keeping of universally accepted time also underpins computing and communications networks. But perhaps the most significant impact of the atomic clock - as in the past with ships and trains - has been on travel.

Nobody now needs to navigate by the angle of the Sun. We have GPS.

GPS technology has revolutionised transportation

The most basic of smartphones can locate you by picking up signals from a network of satellites: because we know where each of those satellites should be in the sky at any given moment, triangulating their signals can tell you where you are on Earth.

The technology has revolutionised everything from sailing to aviation, surveying to hiking. But it works only if those satellites agree on the time.

GPS satellites typically house four atomic clocks, made from caesium or rubidium. Huygens and Harrison could only have dreamed of their precision, but it is still possible to misidentify your position by a couple of metres - a fuzziness amplified by interference as signals pass through the Earth's ionosphere.

That is why self-driving cars need sensors as well as GPS. On the road, a couple of metres makes the difference between lane discipline and dangerous driving.

Meanwhile, clocks continue to advance.

Scientists have recently developed one, based on an element called ytterbium, that will not have lost more than a hundredth of a second by the time the Sun dies and swallows up the Earth, in about five billion years.

How might this extra accuracy transform the economy between now and then? Only time will tell.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published18 January 2017

- Published31 December 2016

- Published27 March 2016

- Published26 March 2016