How Ikea's Billy bookcase took over the world

- Published

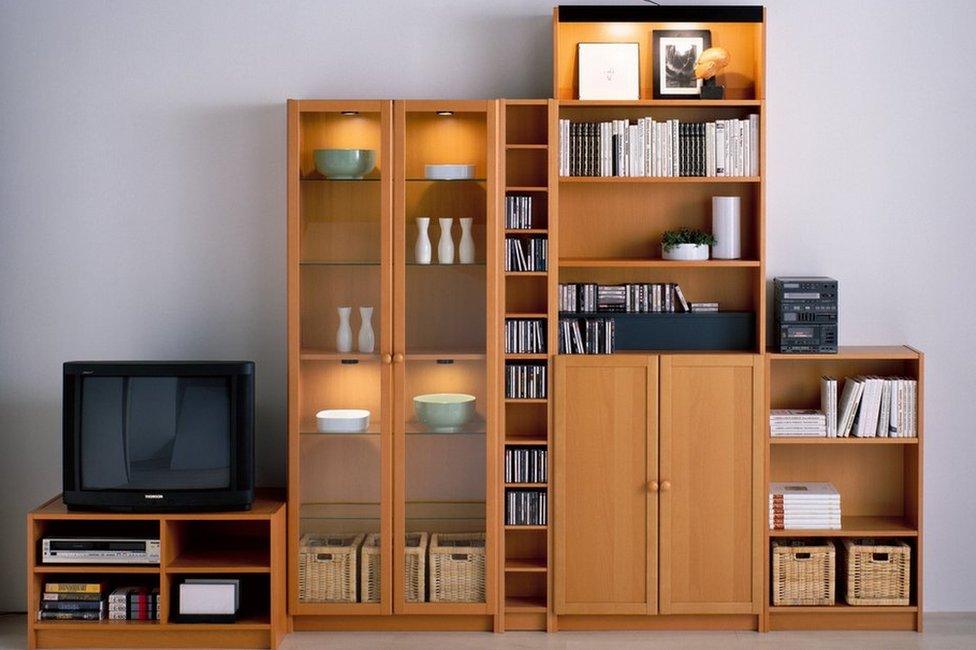

The Billy bookcase is perhaps the archetypal Ikea product.

It was dreamed up in 1978 by an Ikea designer called Gillis Lundgren who sketched it on the back of a napkin, worried that he would forget it.

Now there are 60-odd million in the world, nearly one for every 100 people - not bad for a humble bookcase.

In fact, so ubiquitous are they, Bloomberg uses them to compare purchasing power across the world.

According to the Bloomberg Billy Bookcase Index, external - yes, that's a thing - they cost most in Egypt, just over $100 (£79), whereas in Slovakia you can get them for less than $40 (£31).

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that have helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Every three seconds, another Billy bookcase rolls off the production line of the Gyllensvaans Mobler factory in Kattilstorp, a tiny village in southern Sweden.

The factory's couple of hundred employees never actually touch a bookshelf - their job is to tend to the machines, imported from Germany and Japan, which work constantly, to cut, glue, drill and pack the various component parts of the Billy bookcase.

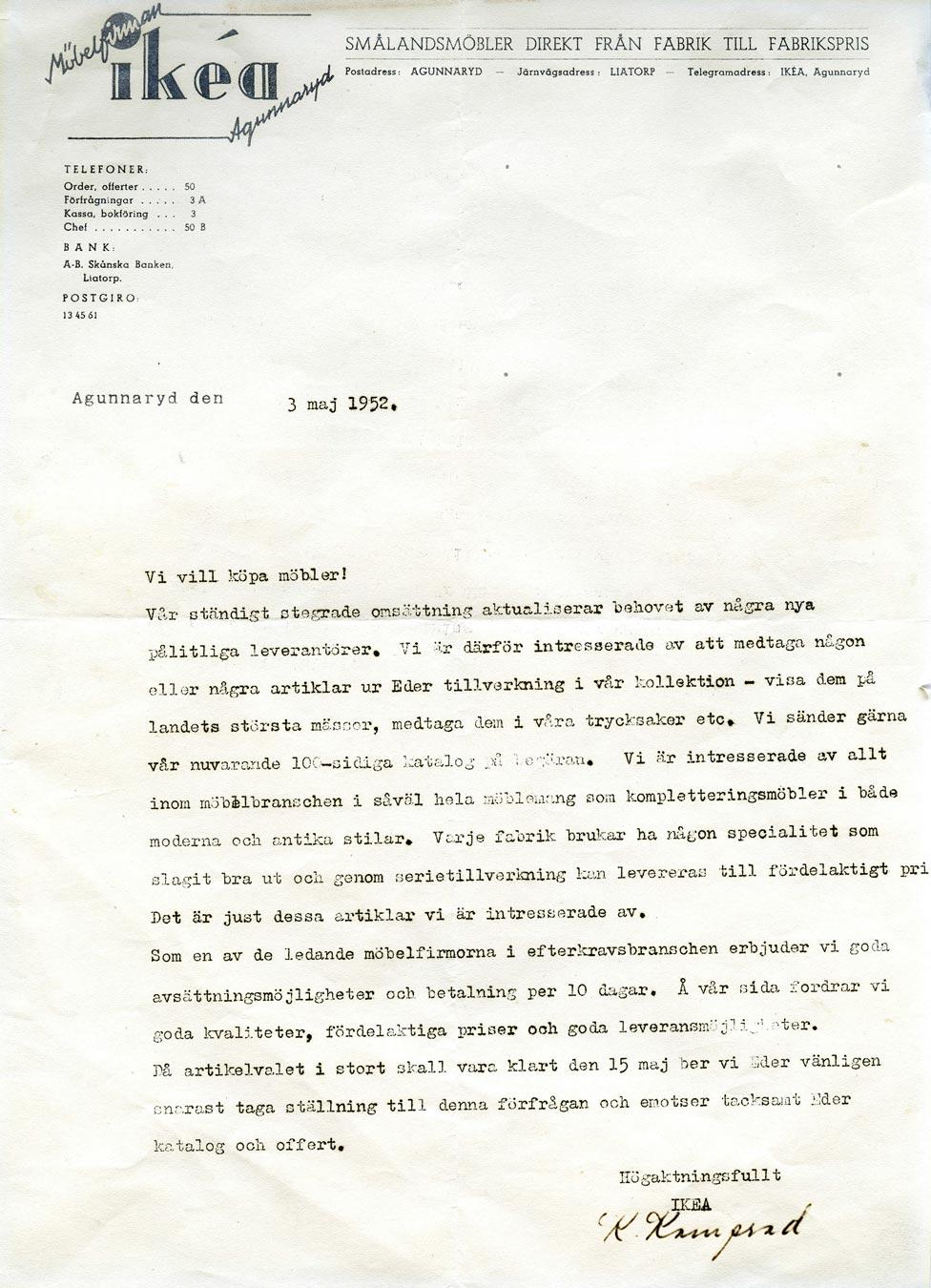

Gyllensvaans Mobler has been making furniture for Ikea since 1952

In goes particle board by the lorry load, 600 tonnes a day, and out come ready-boxed products, stacked six-by-three on pallets and ready for the lorries.

Framed on the wall in the factory's reception is a typewritten letter - the company's very first furniture-making order from Ikea in 1952.

Ikea was not, back then, the global behemoth of today, with stores in dozens of countries and turnover in the tens of billions.

Its founder, Ingvar Kamprad, was just 17 when he started the business with a small gift of cash from his father, a reward for trying hard at school despite dyslexia.

Light bulb moment

By 1952, aged 26, Ingvar already had a 100-page furniture catalogue, but had not yet hit on the idea of flat-packing.

That came a few years later, as he and his company's fourth employee - Gillis Lundgren - were packing a car with furniture for a catalogue photo shoot.

"This table takes up too much darn space," Gillis said. "We should unscrew the legs."

Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad is believed to be the world's eighth richest man

It was a light bulb moment.

Kamprad was already obsessed with cutting prices - so obsessed, some manufacturers had started to boycott him. One way to keep prices low is to sell furniture in bits, rather than paying labourers to assemble it.

Even bigger savings come from precisely the problem that inspired Gillis Lundgren: transport.

Constant tweaks

In 2010, for example, Ikea rethought the design of its Ektorp sofa and made the armrests detachable.

That helped halve the size of the packaging, which halved the number of lorries needed to get the sofas from factory to warehouse, and warehouse to shop. And that lopped a seventh off the price.

Consider another Ikea icon: the Bang mug.

You have probably had a drink from one - with yearly sales reaching 25 million, there are plenty knocking around.

Its design is distinctive - wide at the top, tapering downwards with a small handle, right by the rim - and is not motivated purely by aesthetics.

Ikea has continually modified the design and production of its Bang mug to keep costs down

Ikea changed the height of the mug when it realised it could make slightly better use of the space in its supplier's kiln, in Romania.

And tweaking the handle design made them stack more compactly - more than doubling the number you could fit on a pallet, more than halving the cost of getting them from the kiln in Romania to the shelves in the shop.

It has been a similar story with the Billy bookcase.

It does not look like it has changed much since 1978, yet it costs 30% less. That is partly due to constant, tiny tweaks in both product and production method.

But it is also thanks to sheer economies of scale.

Look at Gyllensvaans Mobler: compared to the 1980s, it is making 37 times as many bookcases, yet its number of employees has only doubled. Of course, that is thanks to all those German and Japanese robots.

Yet a business needs confidence to sink so much money into machinery, especially when it has no other client: pretty much all Gyllensvaans Mobler does is make bookcases for Ikea.

More from Tim Harford

Consider the Bang mug again. Initially, Ikea asked a supplier to price up a million units in the first year. Then it asked: "What if we commit to five million a year for three years?" That cut the cost by a 10th.

Not much, perhaps, but every penny counts. Just ask the famously penny-pinching Ingvar Kamprad: in a rare interview, to mark his 90th birthday, Mr Kamprad said he was wearing clothes he had bought at a flea market.

He is said to fly economy and drive an old Volvo. This frugality may help to explain why he is the world's eighth-richest man - although the four decades he spent living in Switzerland to avoid Swedish taxes may also have something to do with it.

Anyone can make shoddy, ugly goods by cutting corners. And anyone can make elegant, sturdy products by throwing money at them.

Boringly efficient systems

To get as rich as Mr Kamprad has, you have to make stuff that is both cheap and acceptably good.

That is what seems to explain the enduring popularity of the Billy.

"Simple, practical and timeless," is how Gillis Lundgren once described the designs he hoped to create, and the Billy is surprisingly well-accepted by the type of people you might expect to be sniffy about mass-produced MDF.

Sophie Donelson edits the interiors magazine House Beautiful. She told AdWeek the Billy was "unfussy" and "unfettered", and "modern without trying too hard".

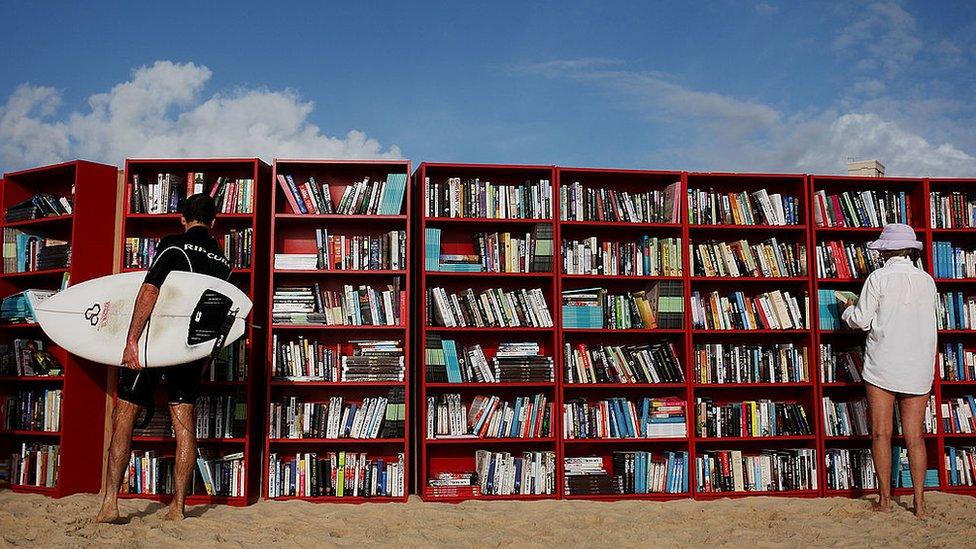

The company celebrated Billy's 30th birthday in 2010 on Australia's Bondi Beach

Furniture designer Matthew Hilton praises an interesting quality: anonymity. Interiors creative Mat Sanders agrees, declaring that Ikea is "a great place for basic you can really dress up to make feel high-end".

The Billy is a bare-bones, functional bookshelf if that is all you want from it, or it is a blank canvas for creativity.

On ikeahackers.net you will see it repurposed as everything from a wine rack to a room divider to a baby-changing station.

But business and supply chain nerds do not admire the range for its modernity or flexibility.

They admire it - and Ikea in general - for relentlessly finding ways to cut costs and prices without reducing the quality of the product.

It demonstrates that innovation in the modern economy is not just about snazzy new technologies, but also boringly efficient systems.

The Billy bookcase isn't innovative in the way that the iPhone is innovative.

The Billy innovations are about working within the limits of production and logistics, finding tiny ways to shave more off the cost, all while producing something that looks inoffensive and does the job.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published24 January 2017

- Published22 December 2016

- Published13 September 2016

- Published30 June 2016

- Published30 October 2012