How the invention of paper changed the world

- Published

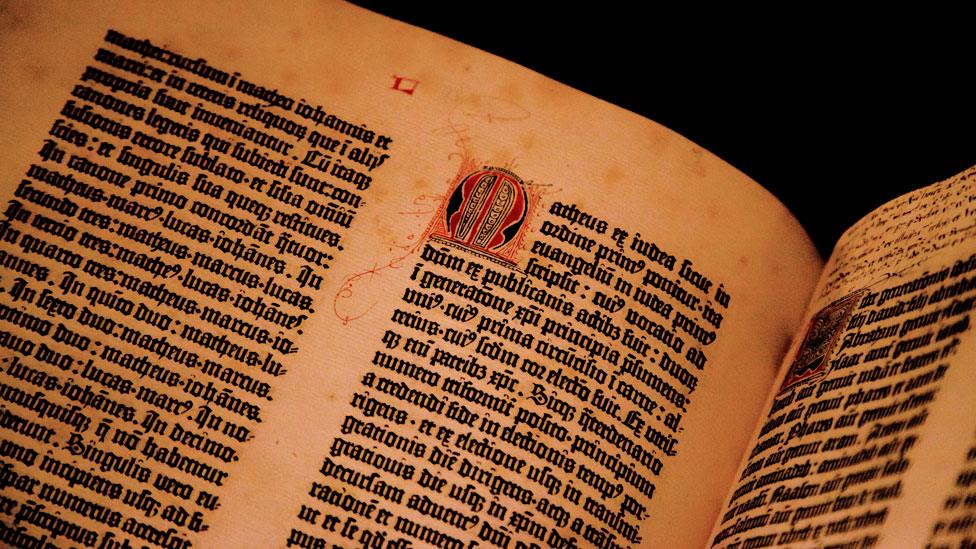

The Gutenberg printing press - invented in the 1440s by Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith from Mainz in Germany - is widely considered to be one of humanity's defining inventions.

Gutenberg figured out how to make large quantities of durable metal type and how to fix that type firmly enough to print hundreds of copies of a page, yet flexibly enough that the type could be reused to print an entirely different page.

His famous bibles were objects beautiful enough to rival the calligraphy of the monks. The crisp black Latin script is perfectly composed into two dense blocks of text, occasionally highlighted with a flourish of red ink.

Actually, you can quibble with Gutenberg's place in history. The movable type press was originally developed in China. Even as Gutenberg was inventing in Germany, Koreans were ditching their entire method of writing to make printing easier, cutting tens of thousands of characters down to only 28.

It is also not true that Gutenberg single-handedly created mass literacy. It was common 600 or 700 years earlier in the Abbasid Caliphate, spanning the Middle East and North Africa.

Still, the Gutenberg press did change the world. It led to Europe's reformation, science, the newspaper, the novel, the school textbook, and much else.

But it could not have done so without another invention, just as essential but much more often overlooked: paper.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Paper was another Chinese idea, from 2,000 years ago.

Initially it was used for wrapping precious objects, but soon people began to write on it because it was lighter than bamboo and cheaper than silk.

This Chinese worker makes paper using techniques devised almost 2,000 years ago

Soon the Arabic world embraced it, but Christians in Europe did not. Paper came to Germany only a few decades before Gutenberg's press.

Why? For centuries, Europeans did not need the stuff.

They had parchment, made from animal skin. It was pricey - a parchment bible required the skins of 250 sheep - but since so few people could read or write, that hardly mattered.

But as a commercial class arose, needing contracts and accounts, cheaper writing material looked more attractive.

The quintessential industrial product

And cheap paper made the economics of printing more attractive too: the cost of typesetting could easily be offset by a long print run, with no need to slaughter a million sheep.

Printing is only the start of paper's uses. We decorate our walls with wallpaper, posters and photographs, we filter tea and coffee through it, package milk and juice in it and as corrugated cardboard, we use it to make boxes.

We use wrapping paper, greaseproof paper, sandpaper, paper napkins, paper receipts and paper tickets.

In the 1870s - the same decade that produced the telephone and the light bulb - the British Perforated Paper Company produced a kind of paper that was soft, strong, and absorbent. It was the world's first dedicated toilet paper.

In fact, paper is the quintessential industrial product, churned out at incredible scale and when Christian Europeans finally embraced paper, they created arguably the continent's first heavy industry.

Endless innovation

Initially, paper was made from pulped cotton. Some kind of chemical was required to break down the raw material. The ammonia from urine works well, so for centuries the paper mills of Europe were powered by human waste.

Pulping also needs a tremendous amount of mechanical energy. One of the early sites of paper manufacture, Fabriano in Italy, used fast-flowing mountain streams to power massive drop-hammers.

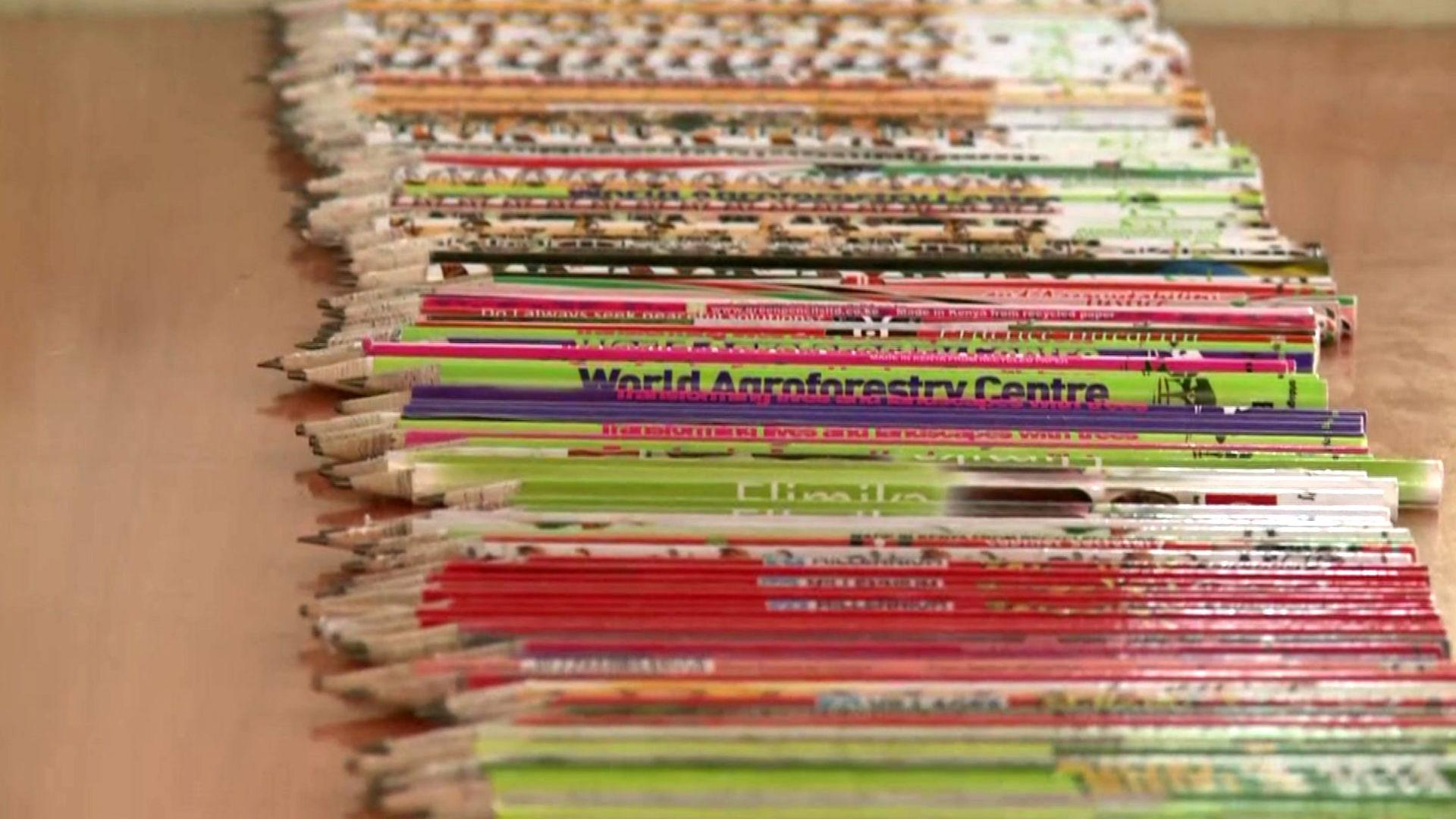

The papermaking process saw endless innovation

Once finely macerated, the cellulose from the cotton breaks free and floats around in a kind of thick soup. Thinned and allowed to dry, the cellulose reforms as a strong, flexible mat.

Over time, the process saw endless innovation: threshing machines, bleaches and additives helped to make paper more quickly and cheaply, even if the result was often a more fragile product.

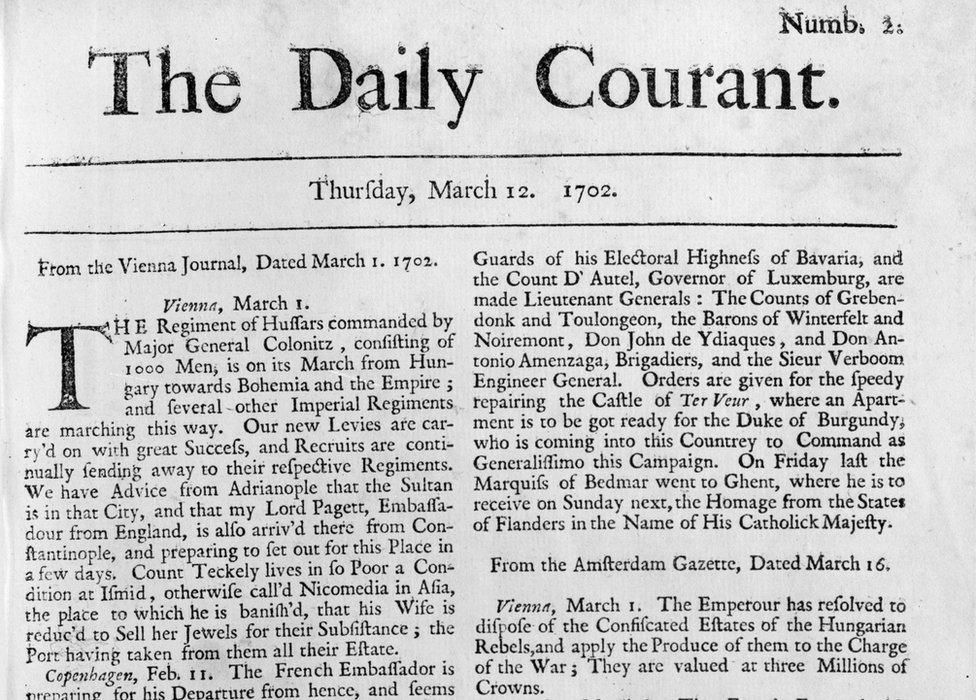

By 1702, paper was so cheap, it was used to make a product explicitly designed to be thrown away after only 24 hours: the Daily Courant, the world's first daily newspaper.

When it began, The Daily Courant only covered foreign news

And then, an almost inevitable industrial crisis: Europe and America became so hungry for paper that they began to run out of rags.

The situation became so desperate that scavengers combed battlefields after wars, stripping the dead of their bloodstained uniforms to sell to paper mills. An alternative source of cellulose was found - wood.

The Chinese had long since known how to do it, but Europeans were slow to catch up.

More from Tim Harford

In 1719, a French biologist, Rene Antoine Ferchault De Reaumur, wrote a scientific paper pointing out that wasps could make paper nests by chewing wood, so why couldn't humans?

When his idea was rediscovered years later, paper makers found that wood is not an easy raw material and contains much less cellulose than cotton rags.

It was the mid-19th century before wood became a significant source for paper production in the West.

Today, paper is increasingly made out of paper itself, often recycled - appropriately enough - in China.

A cardboard box emerges from the paper mills of Ningbo, 130 miles (200km) south of Shanghai, and is used to package a laptop.

The box is shipped across the Pacific, the laptop is extracted and the box is thrown into a recycling bin in Seattle or Vancouver. Then it's shipped back to Ningbo, to be pulped and turned into another box.

When it comes to writing, though, some say paper's days are numbered, believing the computer will usher in the "paperless office". But this has been predicted since Thomas Edison, in the late 19th century, who thought office memos would be recorded on his wax cylinders instead.

The idea really caught on as computers started to enter the workplace in the 1970s and it was repeated in breathless futurologists' reports for the next decades.

Meanwhile, paper sales stubbornly continued to boom. Yes, computers made it simple to distribute documents without paper, but printers made it equally easy for recipients to put them on paper anyway.

America's copiers, fax machines and printers continued to spew out enough sheets of paper to cover the country every five years. After a while, the paperless office became less a prediction, more a punchline.

But perhaps things are finally changing: in 2013, the world hit peak paper.

Many of us may still prefer the feel of a book or a physical newspaper to swiping a screen, but the cost of digital distribution is now so much lower that we are increasingly choosing the cheaper option.

Finally, digital is doing to paper what paper did to parchment with the help of the Gutenberg press: outcompeting it, not on quality, but on price.

Paper may be on the decline, but it will survive not only on the supermarket shelf or beside the lavatory, but in the office too.

Old technologies have a habit of enduring. We still use pencils and candles and the world still produces more bicycles than cars.

Paper was never only a home for beautiful typesetting, it was everyday stuff. And for jottings, lists and doodles, you still can't beat the back of the envelope.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published17 November 2016

- Published27 July 2016

- Published13 April 2016

- Published14 August 2015

- Published14 August 2015