How a razor revolutionised the way we pay for stuff

- Published

The man who founded the Gillette corporation, King Camp Gillette, had some surprising philosophical ideas.

In 1894, Gillette published a book arguing that "our present system of competition" breeds "extravagance, poverty, and crime".

He advocated a new system of "equality, virtue, and happiness", in which just one corporation - the United Company - would make all of life's necessities, as cost-effectively as possible.

Gillette's book called for everyone in North America to live in a single city, called Metropolis.

He imagined "mammoth apartment houses… upon a scale of magnificence such as no civilization has ever known", connected by artificial parks with "domes of coloured glass in beautiful designs".

It would be, he said, "an endless gallery of loveliness". His idea didn't take off.

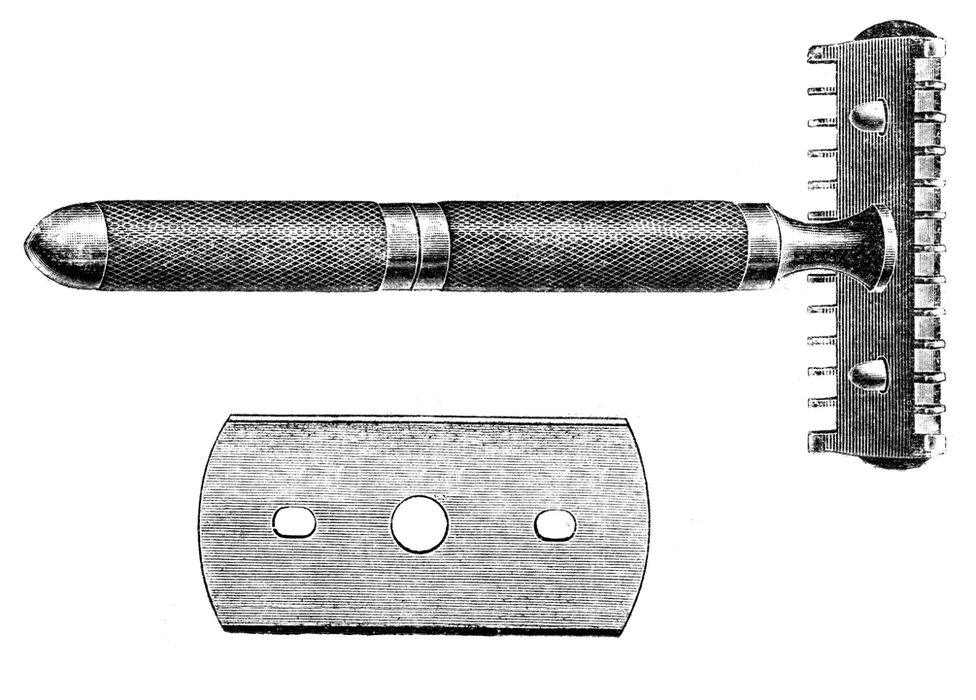

But a year later, in 1895, King Camp Gillette had another brainwave that really did change the world. He invented the disposable razor blade.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

It revolutionised more than shaving. Gillette's blade led to a business model that has become ubiquitous in the modern economy. That model is called two-part pricing.

If you have ever bought replacement cartridges for an inkjet printer, you may well have been annoyed to discover they cost almost as much as you paid for the printer itself.

That seems to make no sense.

The printer is a reasonably large and complicated piece of technology. How can it possibly add only a negligible amount to the cost of supplying a bit of ink in tiny plastic pots?

The answer, of course, is that it doesn't. But for a manufacturer, selling the printer cheaply and the ink expensively is a business model that makes sense.

After all, what's the alternative? Buy a whole new printer from a rival manufacturer? As long as that is even slightly more expensive than the new ink for your current printer, you will reluctantly pay up.

King Camp Gillette realised he could charge people a premium for the blades for his razor

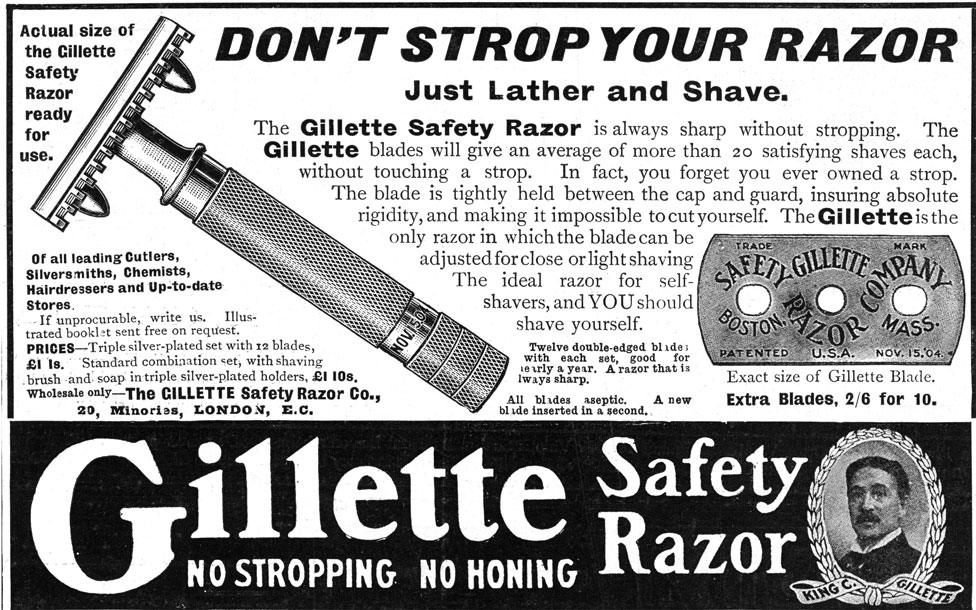

Two-part pricing is also known as the "razor and blades" model, because that's where it first drew attention - draw people in with an attractively priced razor, then repeatedly charge them for expensive replacement blades.

Before King Camp Gillette, razors were bigger, chunkier affairs - and a significant enough expense that when the blade got dull, you would sharpen - or "strop" - it, not chuck it away and buy another.

Gillette realised that if he devised a clever holder for the blade, to keep it rigid, he could make the blade much thinner - and hence much cheaper to produce.

He did not immediately hit upon the two-part pricing model, though. Initially, he made both parts expensive.

Gillette's razor cost $5 (£4) - about a third of the average worker's weekly wage.

The Gillette razor was so eye-wateringly exorbitant that the 1913 Sears catalogue offered it with an apology that it was not legally allowed to discount the price.

It also included an annoyed-sounding disclaimer: "Gillette safety razors are quoted for the accommodation of some of our customers who want this particular razor. We don't claim that this razor will give better satisfaction than the lower-priced safety razors quoted on this page."

The model of cheap razors and expensive blades evolved only later, as Gillette's patents expired and competitors got in on the act.

Nowadays, two-part pricing is everywhere.

Consider the PlayStation 4.

The Sony PlayStation 4, which went on sale in November 2013, has surpassed 40 million sales worldwide

Every time Sony sells one, it loses money: the retail price is less than it costs to manufacture and distribute. But that is OK, because Sony makes its money whenever a PlayStation 4 owner buys a game.

Or how about Nespresso? Nestle profits not from selling the machine, but the coffee pods.

The value of inertia

Obviously, for this model to work you need some way to prevent customers putting cheap, generic blades in your razor.

One solution is legal: patent-protect your blades. But patents don't last forever. Patents on coffee pods have started expiring, so brands such as Nespresso now face competitors selling cheap, compatible alternatives.

Some are looking for another kind of solution: technological.

Just as other people's games don't work on the PlayStation, and non-branded print cartridges may not work in some printers, coffee companies have put chip readers in their machines to stop you sneakily trying to brew up a generic cup.

Nespresso makes more money from selling its coffee pods than the coffee machines

Two-part pricing models work by imposing what economists call "switching costs". Want to brew another brand's coffee? Then buy another machine.

They are especially prevalent with digital goods. If you have a huge library of games for your PlayStation, or books for your Kindle, it is a big thing to switch to another platform.

Switching costs don't have to be financial. They can come in the form of time, or hassle.

If I am already familiar with Adobe's Photoshop software, I might prefer to pay for an expensive upgrade rather than buy a cheaper alternative, which I would then have to learn how to use.

That is why software vendors offer free trials, and why banks and utilities offer special "teaser" rates to draw people in. When they quietly raise the price, many will not bother to change.

Puzzling acceptance

Switching costs can be psychological, too - a result of brand loyalty.

If Gillette's marketing department persuades me that generic blades give an inferior shave, then I will happily keep paying extra for Gillette-branded blades.

That may explain the otherwise curious fact that Gillette's profits increased after his patents expired and competitors could make compatible blades.

More from Tim Harford

Perhaps, by then, customers had got used to thinking of Gillette as a high-end brand, worth paying a premium for.

Two-part pricing can be highly inefficient, and economists have puzzled over why consumers stand for it. The most plausible explanation is that they get confused.

Either they don't realise they will be exploited later, or they do realise but find it hard to think ahead and pick out the best deal.

The irony is that the razors-and-blades model - charging customers a premium for basics such as ink and coffee - is about as far as you can get from King Camp Gillette's vision of a single United Company producing life's necessities as cheaply as possible.

Evidently, it's easier to inspire a new model for business than a new model for society.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published2 January 2017

- Published29 September 2016

- Published19 February 2016