A long term view: The man who took a chance on Pakistan

- Published

Mattias Martinsson put money in Pakistan when most people wouldn't take the risk

On 2 May 2011, Barack Obama announced that al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden had been killed by US forces in Pakistan.

He was shot dead at a compound near the capital, Islamabad. And once again, Pakistan was in the headlines for all the wrong reasons.

A country used to bad news - both politically and economically - it has long been seen as the basket case economy of South Asia because of its slumping foreign reserves, weak currency and lack of foreign direct investment.

It was probably one of the last places on Earth that a foreign investor would think to put their money.

But not Mattias Martinsson. Six months later, in October 2011, he launched Pakistan's first ever foreign equity fund.

In the beginning he couldn't get anyone to back the fund, so he invested $1m (£780,000) of his own cash and that of his partners. Today, that fund is worth $100m.

"It was a tough sell at the time," chuckles the soft-spoken Swede on the phone from Stockholm.

That's an understatement. At one point - soon after the Bin Laden killing - things got so bad that furious investors stoned the exchange because of the falling share prices.

"Then the US military bombed a Pakistani military base, and Pakistan initiated a blockade of the routes for Nato supplies. The market went down 10%," Mr Martinsson says.

You might also be interested in:

But he stayed in the stock market and in 2012 things started to turn around, with a tax amnesty the government launched to encourage the Pakistani diaspora to repatriate money.

"The market went up and we raised $50m in three months," he recalls.

It also marked the first time in decades that more money was coming into Pakistan than going out.

Outperforming

Almost a decade later, Mr Martinsson feels vindicated.

That's because on 1 June 2017, Pakistan enters the MSCI Emerging Markets Index - a sign that things are turning around. And investors are already starting to pour in.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index, external is made up of 23 high-growth economies including India, China and Brazil.

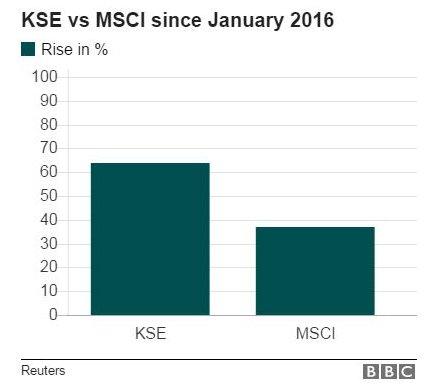

Pakistan's main index, the KSE 100 has consistently outperformed the index.

If you had invested $100 into the KSE in January last year, it would now be worth $164. If you had put it into the MSCI, it would only be worth $137. That's a success that helped make the case for it to be included.

Being in the Emerging Markets Index is a reputational reassurance to investors about the growth prospects and transparency of companies in that country.

Pakistan used to be a part of the index, but was downgraded to frontier market because of the exchange's decision to shut down for four months in late 2008 after prices dropped dramatically. That meant foreign investors couldn't get their money out.

"We were kicked out in 2008 after the financial crisis because of measures Pakistan took at the time to stop foreign funds from fleeing the country. Obviously foreign investors got a rude shock," says Nadeem Naqvi, the Karachi Stock Exchange's managing director.

"We did a lot of lobbying and reforms to get re-included again into this index," he tells me from Karachi. And he assures me and investors, that the KSE will be a liquid market.

"Parliament passed the Pakistan Stock Exchanges Act in 2012, which has improved corporate governance and reforms to prevent a reoccurrence of what happened in 2008," he says.

Chinese impact

Pakistan's gross domestic product (GDP) has also soared over the last few years, a lot of that is thanks to the growth in the middle classes, in part fuelled by the Chinese investment boom that is part of Beijing's One Belt One Road initiative.

China is spending $46bn building roads, ports and highways in Pakistan as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

"It's just starting," says Mr Naqvi. "You'll see the real impact in the next 12 to 24 months. That'll be an added impetus to the growth rate."

Chinese investors have also bought into the Pakistan Stock Exchange, and they now own 40% of it.

Under Xi Jinping (right) China is investing heavily in developing infrastructure in Pakistan

"All of this is going to add to the confidence of the middle class to spend more, and add to domestic demand," Mr Naqvi says. "In five to six years the growth rate should average out to above 6%."

Having said that, though, there have already been signs of trouble on the CPEC routes. In the last few months security issues have plagued some of the sites, raising concerns over the long term viability of the project.

And there are some real concerns for investors to think about before entering Pakistan.

"It's great for Pakistan's ego... they love the idea that [they] are no longer in the frontier market index," says Mark Mobius, executive chairman at Templeton Emerging Markets Group.

He has been investing in Pakistan for the last 15 years, and on the whole is bullish about the prospects there.

"[But] there's a real problem of government change, tension with India is very critical," he warns,

'Good story'

Still, despite major setbacks like the killing of Osama Bin Laden and former Pakistani PM Benazir Bhutto's assassination, the KSE has continued to rise and in fact this year has out-performed other regional indices making it one of Asia's best performing, external.

Just look at this 20-year chart of the KSE 100 Index.

"There is a general impression that the last 20 years have been a disaster in Pakistan," Mr Martinsson tells me.

"But this is one of the best equity markets in the world. This was always a good investment story. You just have to be brave and take the risk."

- Published19 May 2017

- Published12 May 2017