Why should we care about free trade?

- Published

The next time you head down to your High Street for a bit of weekend shopping, take a minute to look at where that pair of jeans you're eyeing is made.

Chances are, they will have been made in Bangladesh, Vietnam or even Indonesia, stitched together by a worker in a factory somewhere, and then shipped over to you at a fraction of the cost these jeans would have set you back a few decades ago.

How does this happen?

Free trade.

Simply put, it's the practice of removing restrictions on imports and exports between countries.

The more you lower tariffs - or taxes that countries put on goods coming from elsewhere to protect their own industries - the more buying and selling there will be, or so the theory goes.

Free trade evangelists will tell you that the optimum scenario is a future where there will be zero tariffs on goods going from one country to another, and we will all be buying what we need from country A because we will be able to sell them the things they don't have from country B.

Makes sense?

Except there's a problem.

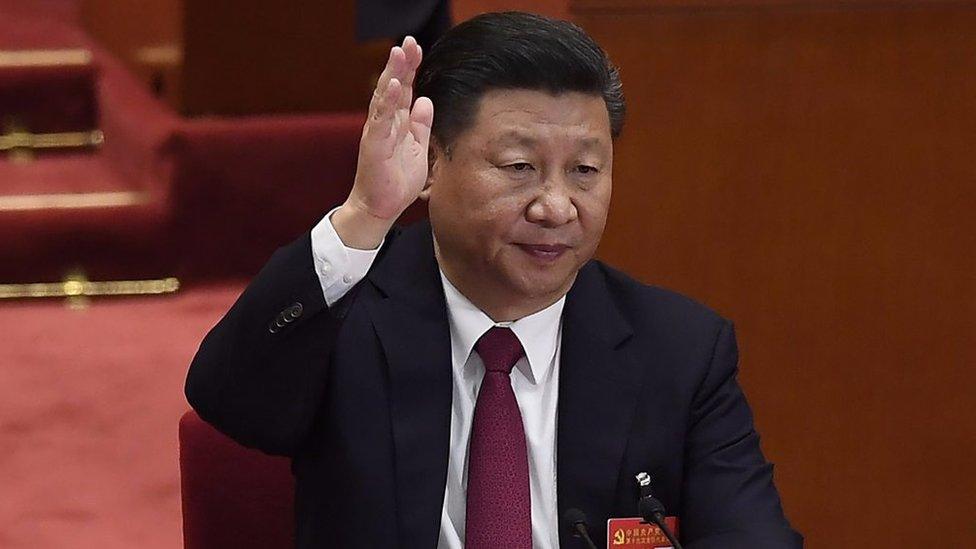

The US President Donald Trump doesn't agree with this vision. He's railed against free trade deals, external, saying globalisation has "wiped out" America's middle class.

That's ironic, given that up until recently US and American companies have been the biggest proponents of free trade deals.

But President Trump wants "fair trade" instead, and is pushing an America First strategy.

He pulled out of the Obama-backed 12 nation Trans Pacific Partnership agreement - or TPP - soon after he was elected, because he said it was a bad deal for US workers.

President Trump has also threatened to pull out of the North American Free Trade Agreement if no deal can be reached with trade partners Canada and Mexico, wants to renegotiate a trade agreement with South Korea (although not much mention of it on his recent trip) and has called free trade agreements a "disaster".

In short, he doesn't like them.

For many of the delegates at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit in Danang, President Trump's trade tantrums have been seen as a sign of US disengagement from the region - so they're still continuing with the Trans Pacific trade deal, just without the US, with the participating countries known as the TPP-11.

It's a sentiment I've heard a lot at the APEC meeting this week - that trade negotiations will go on with or without the US.

As the Australian Trade Minister Steven Ciobo told me, "History has taught that countries can put up tariff walls or put up barriers to trade thinking that's in some way going to enrich those countries. Well, they're the ones that are going to be the worse off."

So if free trade creates new markets, lowers prices and creates jobs, then why isn't everyone a fan?

Who loses out?

Part of the problem is that there will always be winners and losers in this game.

Take that pair of jeans example again.

The factory worker in Asia, who perhaps had been working on a farm before getting a job in the factory, will definitely benefit thanks to a stable income, and the prospect of higher wages.

You too will benefit - you will pay far less for a pair of jeans you're after than you did perhaps a decade or so ago.

But what happens when there's a third party involved - ie, the person who used to make the jeans in a factory down the road from you, before the manufacturing line was outsourced overseas?

Not everyone is better off, Scott A Wolla and Anna Esenther from the Federal Bank of St Louis point out, external: "The costs and benefits of trade extend beyond the actual buyer and seller in the transaction.

"And once third parties are included, it is clear that trade can create winners and losers."

Generally the winners are the consumers and companies selling the products that are being manufactured elsewhere.

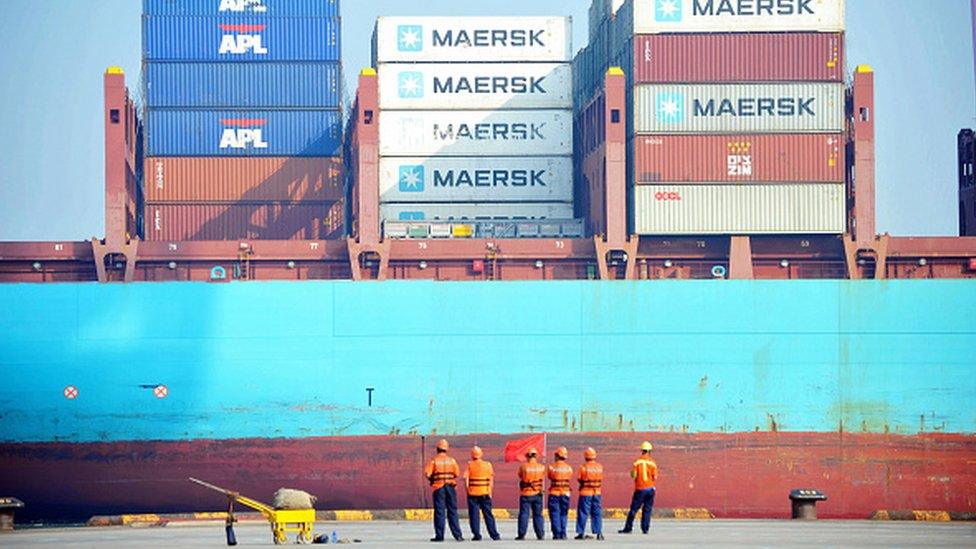

Also in this box are the countries that have benefited most from the free trade movement over the last few decades - China, India, much of South East Asia - that turned into Factory Asia, churning out products for the whole world, pushing prices for us down and their living standards up.

But there are losers. The companies that can't compete in this new marketplace where costs are lower. They shut down their businesses, and workers lose jobs.

Sidelined

That anger of being left behind and not participating in the benefits of free trade is what helped Donald Trump to win the election, according to many observers.

But it's not just because these workers were out of jobs. It's also because there hasn't been what the President of Peru Pedro Pablo Kuczynski called a lack of "technical education."

"This creates a very large dissatisfied class which is looking for people to blame for their problems," he told me on the sidelines of the Apec summit.

"You can see that in the elections in the US a year ago. The anger led to that result."

But even as President Kuczynski remains a free trade advocate, he admits it isn't easy to entirely mitigate the negative impact of globalisation.

"Peru has almost zero tariffs," he said "but it still has some protectionist measures in agriculture and we need to change that."

So even the freest of free traders has to put some measures in place to protect domestic industries.

Trump trade

The anti-trade rhetoric has been a key feature of President Trump's first term. But what it actually achieved?

Beyond pulling out of the TPP - which was unlikely to have been approved by the US Congress without more changes - not very much.

President Trump hasn't renegotiated any deals yet with China or Japan.

He's not won any major concessions.

A few companies have made high profile announcements of investments and job creation in the US, but nothing like he had said would happen on the campaign trail.

And according to this BBC poll, American workers aren't feeling that much more optimistic under President Trump, despite his assurances that jobs are coming back to the US.

Perhaps the businessman in President Trump realises that while talking about trade negatively is in vogue now and sells well with the voters back home, it's not particularly practical.

Rise of the robots

"It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than buy," wrote Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations, external. "If a foreign country can supply with us a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry."

In theory, this makes perfect economic sense.

But in practice, there will always be winners and losers from free trade. And it's not just that - automation is the next big trend for businesses looking to save costs, and that will undoubtedly have more of an impact on job security than free trade ever did, and mostly in the emerging economies that benefited from the low-cost manufacturing jobs.

Both governments and businesses need to address how to mitigate the negatives of free trade, or face a protectionist backlash from their citizens in the future.

- Published25 October 2017

- Published24 October 2017

- Published24 October 2017

- Published25 October 2017