UK unemployment falls to 1.44 million

- Published

- comments

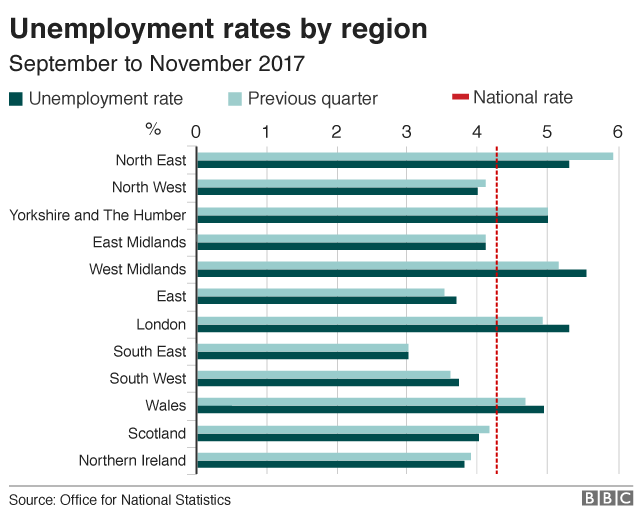

UK unemployment fell by 3,000 to 1.44 million in the three months to November, official figures show.

The number of those in work increased sharply and wages rose at their fastest rate in almost a year, the Office for National Statistics said.

That leaves the UK's unemployment rate at a four-decade low of 4.3%.

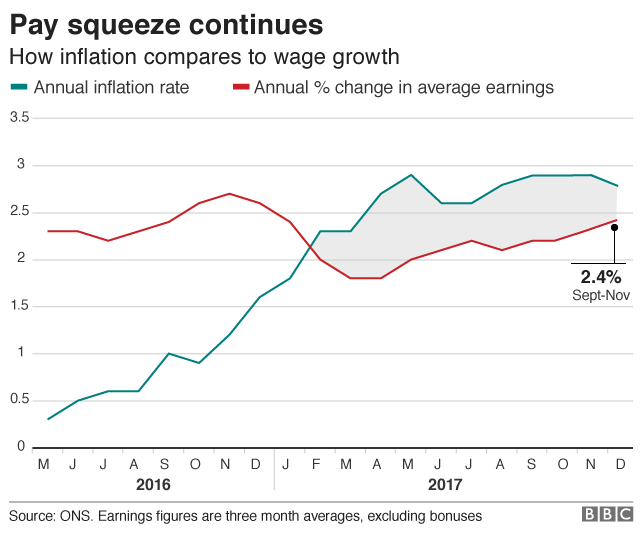

But the growth in wages at 2.4% remained below inflation at 3.1% in November, leaving real wages lower for than a year earlier.

"Demand for workers clearly remained strong," said ONS statistician David Freeman.

"Nevertheless, inflation remains higher than pay growth and so the real value of earnings continues to decline."

The pace of job creation was faster than economists had predicted. The ONS said the number of people in work rose by 102,000 in the three months to November, taking total employment to a record 32.2 million.

Higher consumer price inflation, due to weaker sterling, has left real pay 0.5% lower than a year earlier, but rising wages are beginning to close the gap.

"Today's jobs numbers once again strongly suggest that the UK economy is on a firmer footing than many had anticipated following the EU referendum vote," commented James Athey, senior investment manager at Aberdeen Standard Investments.

Analysis: Andy Verity, BBC economics correspondent

The labour market is tighter than it's been in decades. Unemployment is at a 42-year low of 4.3%. And in 17 years there have never been more vacancies: 810,000 of them.

That high demand for labour should combine with a slower supply in the past year to produce a higher price of labour. Translation: higher wages. It should mean workers have greater bargaining power - and therefore greater capacity to bid up their wages. And employers who want workers the most should start to pay more to attract them.

And indeed, there was a modest uptick in average earnings - now £490 a week, up £11 a week or 2.4% from last year (versus 2.3% previously). But it's still less than inflation - a real-terms pay cut of 0.5%. Why aren't workers demanding more?

Here's a clue that may partly explain it. There's been a shift as the number of self-employed people drops and the number of full-time employees rises. In a climate of continuing economic uncertainty, many workers are only now getting the job security they would like. Before you demand a bigger pay rise, you first have to get over your relief at finding a secure full-time job.

Mr Athey said the better-than-expected jobs figures went "some way" to justifying the Bank of England's November interest rate rise.

But he said shrinking real wages continued to put pressure on consumer spending, which was the linchpin of the UK economy, "a reminder that the economy is not on completely stable ground."

John Hawksworth, chief economist at PwC, said the data showed "the UK jobs engine kicking back into life".

He said a tighter labour market, with higher demand for the available workers, would make the Bank of England more likely to raise interest rates.

"If this pattern of solid jobs growth and a gradual pick-up in earnings growth were to persist through the year, then this could push the MPC towards a further interest rate rise later in 2018."

Ian Stewart, chief economist at Deloitte, said he expected wage growth to edge higher this year: "The worst of the squeeze on incomes is probably behind us."

However, Ben Brettell, senior economist at stockbrokers Hargreaves Lansdown, said new technology and global competition were still weakening workers' bargaining power: "It looks like low wages now explain low unemployment, rather than low unemployment acting as a catalyst for better pay."

The pound rose sharply following the news of the strong jobs figures, moving above $1.41 before falling back slightly.

It also hit a six-week high against the euro. Mid-morning the pound was worth €1.1431.

- Published23 January 2018

- Published13 December 2017