Four reasons Trump is hanging tough on trade

- Published

- comments

First they came for the washing machines.

Then the solar panels.

And now steel and aluminium.

President Donald Trump has always made it clear he wanted a new approach to trade.

And in the White House's proposals for new tariffs on steel and aluminium - following similar moves on domestic appliances and green infrastructure - he has revealed the latest push to put America First into action.

Given the statistics since the Second World War suggest that global economic growth is linked to higher levels of free trade, this might seem a contrary approach for the largest economy in the world.

There are a myriad of economic studies which argue that protectionism ultimately reduces employment and increases prices for consumers.

Adam Smith, often described as the father of free market economics, said: "It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy".

Just as it makes sense for a family to "trade" with others for its own well-being - buying and selling goods - it makes the same sense for countries, Adam Smith argued.

More trade, freer trade, makes economic sense, proponents argue.

So, why is President Trump taking a different view?

1. Headline grabber

The general trend of global economics is towards freer trade, whatever the noise around protectionism.

The latest World Trade Organization (WTO) statistical review revealed that trade restrictive measures had fallen to their lowest level since 2008.

So, a threatened increase in tariffs grabs headlines, but its economic effects will be at the margins given the fundamentals underpinning global trade flows.

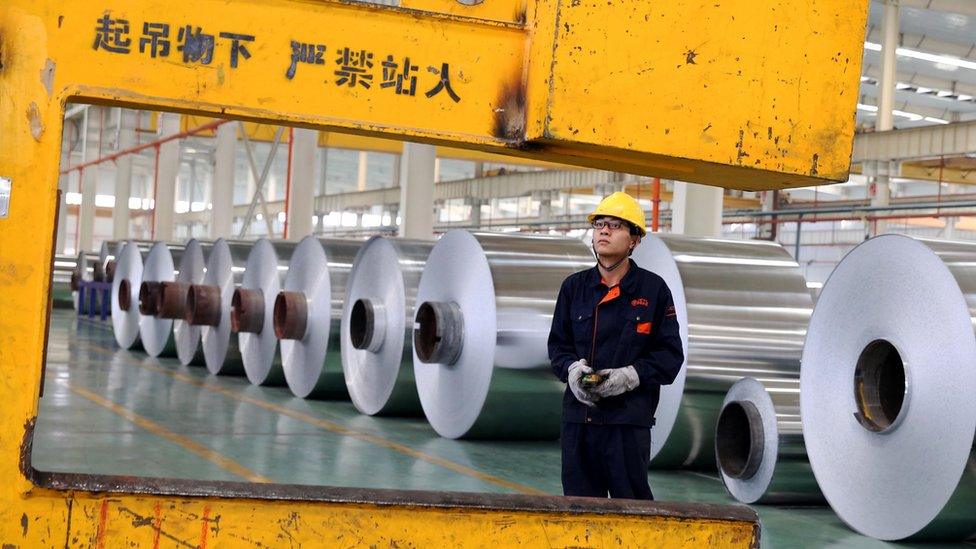

Cheap imports have been blamed for a downturn in the US steel industry

2. Easy political argument

The gains from free trade - for example, lower consumer prices because of the reduced cost of imported goods and the reduction in poverty in far off countries - are diffuse, distant and difficult to quantify.

Conversely, the "impact" of cheaper imports - for example a closed factory - is concentrated and easy to see.

During the Presidential campaign I visited Monessan, Pennsylvania, the heart of America's rust belt.

It used to be a steel producing town of 40,000 people.

That number has fallen to 7,000 and the town is scarred by the derelict skeletons of once prosperous factories.

Unemployment and poverty rates are crippling high.

You can see a short video of my interview with the town mayor, Lou Mavrakis, from 2016 here.

His anger is palpable.

In such a situation, it is relatively straightforward to focus on cheaper imports as the cause of the problem, despite other factors - such as a change in the type of high-tech steel markets are demanding - being equally significant.

America also lacks the type of unemployment safety net and skills retraining common across Europe - so the effects of factory closures are starker.

With such a toxic mix, President Trump - with the crucial mid-term elections approaching - is making a political argument to the voters of Pennsylvania.

I will block cheaper steel imports and save jobs.

Even if the economics suggest that - in aggregate - the opposite will be the case.

The WTO has admitted that gains from free trade are "often uneven"

3. Short-term reality

President Trump is arguing that global free trade has been nothing of the sort.

It has in fact been asymmetric trade, more helpful to emerging markets than to established ones.

This approach to trade - as a zero-sum gain of "you win, therefore I must lose" - is again disputed by economists.

The WTO says that protectionist measures "ultimately leads to bloated, inefficient producers supplying consumers with outdated, unattractive products, in the end, factories close and jobs are lost despite the protection and subsidies".

"If other governments around the world pursue the same policies, markets contract and world economic activity is reduced."

Which will have a negative impact on America.

But long-term economic risk is of less concern to Present Trump than short-term realities.

The WTO has admitted, belatedly some would argue, that the gains from free trade are "often uneven" and "may have led to rising wage inequality".

Those at the lower end of the income scale are particularly affected.

That downside - smaller than the overall gains of free trade but still significant - is President Trump's focus.

4. Mighty domain

The final reason, I believe, is a signal to the world.

President Trump's policy is not just America First, but America Decides.

He is attempting to show that it will be for America to call the tune on trade, whatever the warnings from Theresa May about her "deep concern" about protectionist moves.

Free trade deals with the US - with the UK for example - will be on America's terms.

It was John Wayne who - quoting the words of John Mitchum - said of America that "my pulse runs fast at the might of her domain".

President Trump - I would imagine - feels similar.

- Published5 March 2018

- Published3 March 2018

- Published2 March 2018

- Published28 February 2018