Would you choose a partner based on their 'citizen score'?

- Published

Audrey Kuah says Chinese consumers are "optimistic" about the digital economy

Imagine if everything you did on Facebook or Twitter counted towards a government-imposed 'citizen score'.

All your online behaviour would be analysed and assessed to come up with a measure of your online reputation, character and trustworthiness.

This could then be used by employers to decide whether to offer you a job, by banks to decide whether to give you a loan, or even by prospective partners.

Well, China is planning something like this called the Social Credit System. Details are sketchy at this stage but it is due to be up and running by 2020.

China's "Great Firewall" - its internet censorship programme - already controls access to many Western news websites, as well as Google, Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. But anything its 1.4 billion citizens say or do on the country's hugely popular alternative social media sites, WeChat and QQ, could soon affect their Social Credit System rating.

James Gautrey says the Chinese government wants to see what people are "thinking and doing"

Online chat services must also now verify users' identities, credit score them, and keep a six-month log of group chats - all information that could prove useful for the Social Credit System.

"WeChat has a billion users," says James Gautrey, a technology specialist at investment manager Schroders. "So by capturing its data, the government can see what all those people are thinking and doing. It's a dream for them."

Many individuals and businesses have been side-stepping these draconian controls by using virtual private networks (VPNs) - encrypted proxy services that shield users' web activities from prying eyes.

But last year Beijing ordered the country's three state-owned internet providers, China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom, to block access to unauthorised VPNs. And now the government has demanded that websites, such as shopping giant Alibaba, remove any reference to them.

EXPLAINED: What is a VPN service?

The government has also been investing in physical surveillance technology, including building what it calls "the world's biggest camera surveillance network", and giving police officers sunglasses equipped with facial recognition technology to scan crowds for criminals.

Chinese businesses that rely on VPNs to connect to foreign customers and internet content are alarmed.

But remarkably, Chinese consumers don't seem too concerned, according to a major piece of research by Dentsu Aegis.

Its Digital Society Index, based on interviews with 20,000 people, finds that Chinese consumers trust the digital economy more than any other nationality - 70% believe it will have a positive impact on society.

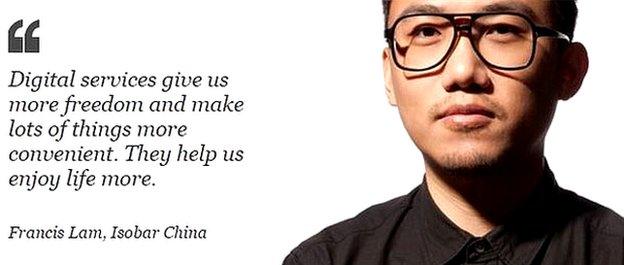

Francis Lam, head of technology and innovation at Shanghai-based marketing agency Isobar China, thinks he knows why.

"Digital services give us more freedom and make lots of things more convenient," he says. "They help us enjoy life more."

China's burgeoning and increasingly creative tech sector is also a source of pride for a country that lagged behind rival nations in this area until recently.

"Chinese technology companies are no longer just copycats," Mr Lam says.

"People feel proud of the advances made and of how they affect our status in a global sense. So they are willing to try anything new."

While China's technology sector remains relatively small, accounting for just 3.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016, it is expanding fast.

WATCH: Huawei 'too competitive' for US

GDP growth in the city of Shenzhen, dubbed "the Silicon Valley of hardware", hit 8.8% last year, outstripping Hong Kong.

And three months ago, the country's biggest tech company, WeChat and QQ operator Tencent, overtook Facebook to become the fifth biggest listed company in the world.

Government support for the sector is a major driver of its success.

The Chinese government's "Great Firewall" shielded Tencent from powerful rivals such as Facebook, and it continues to help "new economy" companies - particularly those working in hi-tech areas such as robotics and artificial intelligence (AI).

"Becoming a world leader in the use of robotics is a priority for China," says Audrey Kuah, who leads Dentsu Aegis' Global Data Innovation Centre in Singapore.

"In 2016, it installed around 90,000 [robot] units, or one third of the global total, and this will nearly double to 160,000 units by 2019."

More Technology of Business

Despite the rise of the robots, 65% of people think emerging digital technologies will create more employment opportunities, not fewer, according to Dentsu Aegis.

"It is remarkable that optimism about job creation remains so high despite the rapid changes to China's industrial base," Ms Kuah says.

Their confidence comes as no surprise to Mr Lam, though.

"People are not worried about how automation will affect the jobs market," he says. "They trust the government to manage that."

The Chinese made mobile payments worth $9tn in 2016, compared to $112bn in the US, and they use social media sites like WeChat to pay parking fines, make a doctor's appointment, or order a takeaway - as well as to communicate with friends and relatives.

Even as President Xi Jinping tightens his grip on power, China's digital economy is booming

"Digital services are so pervasive in China, it's really less of an option not to participate," says Mr Gautrey.

"We have nothing you can really compare to WeChat, but it's a very compelling proposition."

And with cash rapidly becoming obsolete in cities such as Shanghai and Beijing, even older Chinese people are being ushered into the digital age.

"The rise of the cashless society means there is not really a problem with senior people being left behind in China, especially in the big cities," Mr Lam says.

The huge popularity of digital services has a downside, though.

Internet addiction affects an estimated 24 million 16-to-24-year-olds, with a recent report from the China Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) indicating that 87% of those in this age group checked WeChat or QQ at least once every 15 minutes.

While the Social Credit System may sound scary to Westerners, Mr Gautrey says: "When you talk to people who have lived in China about the Social Credit System they tell you it has been happening for years, all that is changing is it is being digitised."

For Mr Lam, the situation is even more clear-cut.

"Obviously it depends how the data collected is used," he says. "But why shouldn't the government use technology to keep us safe and secure?"

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external