Meet the female 'artpreneur' making a splash online

- Published

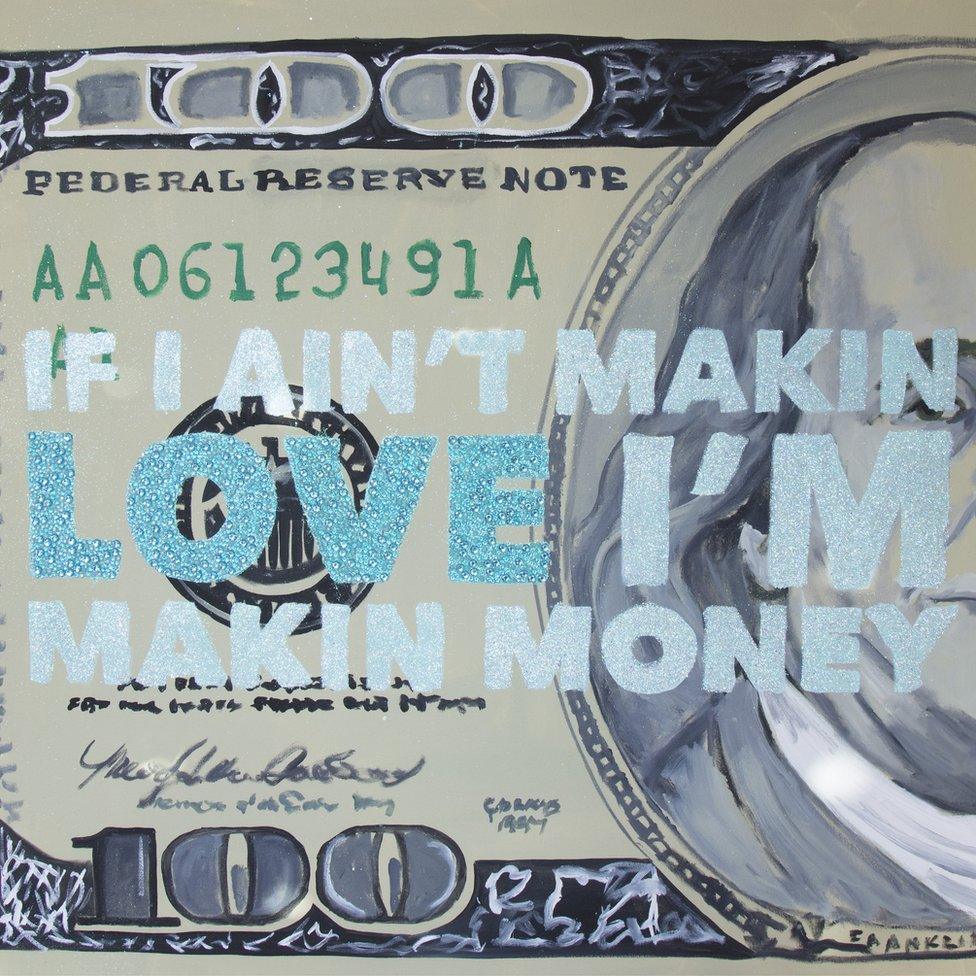

Ashley Longshore's art has been bought by Hollywood celebrities

Buying a piece of art has long been considered an investment, of time as well as money, requiring visits to galleries and trips to auction houses.

But technology is changing the way we interact with, buy, and sell art. And artists are adapting their creative processes to suit a changing landscape.

"There's never been a better time to be an artist in the world," says Ashley Longshore.

The US artist's paintings can be found hanging in the homes of Hollywood celebrities such as Salma Hayek, Penelope Cruz and Blake Lively.

"Art school teaches you that galleries are where you have to be. Galleries told me that I would never make it so I started to think; how could I build my own empire?" she says.

Ashley started using social media - Facebook, Instagram and others - to showcase her art and attract new buyers. Selling direct cuts out the middleman and puts artists back in control, she says.

Ms Longshore says her dream "is a world full of wealthy artists"

"When you buy through a gallery you're investing 50% in the middle man - it screws up the pricing of art. I want artists to see themselves as entrepreneurs - 'artpreneurs' - who have control over what they're putting out," she says.

It's a strategy that has worked well. She has sold multiple works online, including one for $50,000 (£35,000). Paying subscribers get access to limited-edition works as well.

Online art sales are growing worldwide. Online sales reached an estimated $3.75bn in 2016, up 15% from 2015. This represents an 8.4% share of the overall art market, up from 7.4% the year before, according to the 2017 report on the online art market from insurers Hiscox, external.

In contrast, global auction sales fell 19% over the same period.

Iain Barratt, owner of the Catto Gallery in London, recognises that an online presence is important, but is sceptical that social media is the answer to increased sales.

"A lot of social media is just noise. Our artists are on Instagram but they're followed by other artists most of the time, not clients," he says.

"We've had a few indirect sales on social media, but nothing to speak of really."

Traditional auction house Christie's says buyers are spending more online

His gallery typically sells works for £5,000-20,000, and Mr Barratt believes that the more expensive the painting the more reluctant customers are to buy online.

"Above a certain price people want to come in and see the art. On a computer, it just doesn't come across the same way. You want to find out more about it," he says.

"Seeing a piece of art in the flesh - nothing quite beats it."

For the auction house Christie's, which was founded 250 years ago, embracing new technology has been an interesting journey.

"We test and learn with online all the time," says chief marketing officer Marc Sands.

"At the beginning we thought no-one would spend a lot online. Five years ago the average sale online was $2,300, now it's just under $8,000."

In 2017, a third of Christie's new buyers came via the web and online sales totalled £56m, up 12% on the year before.

More Technology of Business

The company now runs 80 to 100 online-only auctions a year, but Mr Sands points out that not all types of art sell well online.

Old masters, paintings created before about 1800, have an older buying demographic "so that market doesn't lend itself well to being sold online", he says.

Does he see online-only art platforms, such as Artsy and Artfinder, as a threat?

"They're a little bit of competition," he says. "Their user base is a bit cooler. They're the new kids on the block so they're quite interesting to work with."

Christie's has recently worked with Artsy on some online auctions, and Mr Sands thinks such collaborations will become more common.

Artists sell their art direct on marketplaces such as Artsy

"We want elements of their audience and they need the supply of art. This sort of model could be the future," he says.

Artsy co-founder Sebastian Cwilich certainly thinks the traditional model of selling art at galleries and auction houses is changing.

"The notion that you can open a location to sell your art and hope that the right people just walk through the door is almost quaint," he says.

"Every industry is leveraging technology to run their business better. We need to embrace new technology. Consumers are much more comfortable buying online, so why not art?"

Having a good online and social media presence certainly allows galleries, auction houses and artists to access a wider customer base and to connect with new buyers.

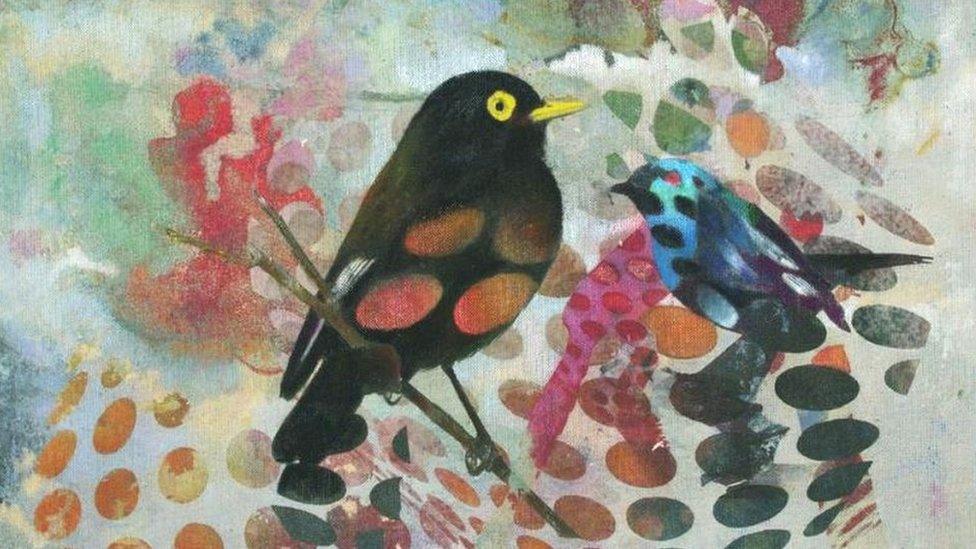

But for emerging artists like Emily Ursa, it can feel difficult to get noticed.

Artist Emily Ursa says "it's hard to stand out" on social media

"Social media is an amazing platform for so many," she says, "but you have to beware because you're one of thousands and thousands.

"Things lose their value on social media and become very throwaway, so it's hard to stand out."

At a gallery exhibition customers can see the work that's gone in to a painting up close, she says.

"It gives it a sense of importance... it's a whole experience, it changes the value of the work."

To artists who say online platforms are the future, Catto Gallery's Iain Barratt has a rather bleak response: "Good luck to you. Where will you be in 30 years time? We've had a 20-year relationship with some of our artists here."

But from her studio in California, Ashley Longshore has little time for that sort of opinion.

"With a gallery you never know who your clients are. I'm creating something tangible - I'm a business person, I want to create money from it. Why wouldn't I use every single avenue I can?

"My dream is a world full of wealthy artists."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external