The Indian women lighting the way for change

- Published

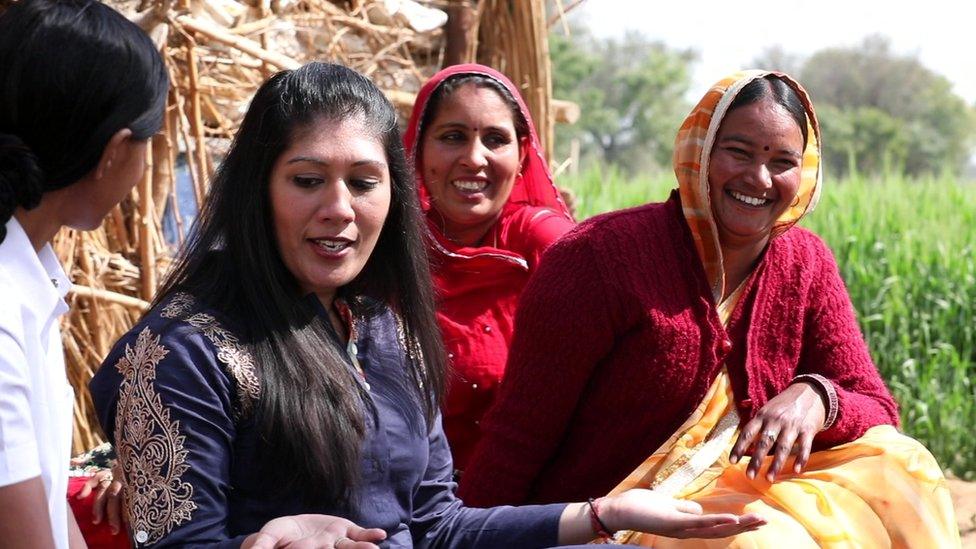

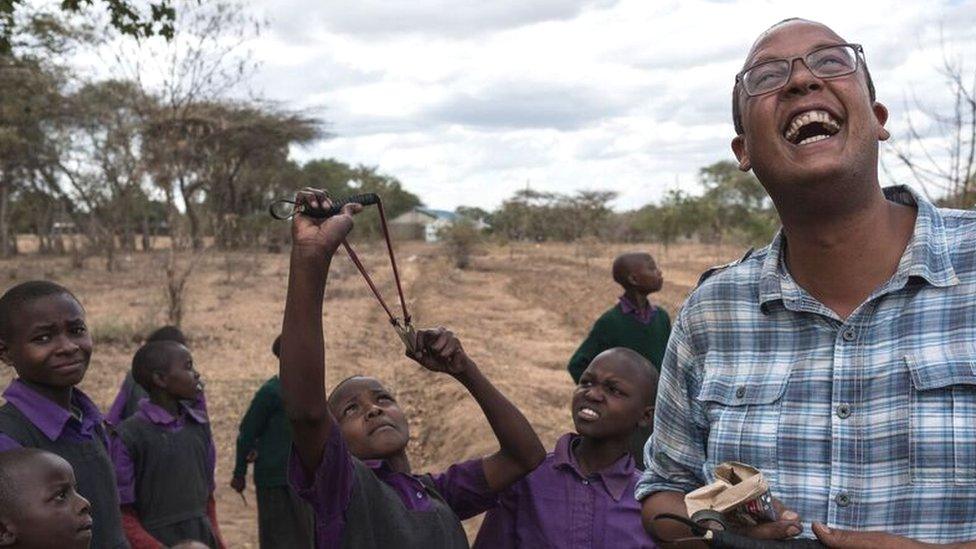

Frontier Markets founder Ajaita Shah with some of the women in her local sales force

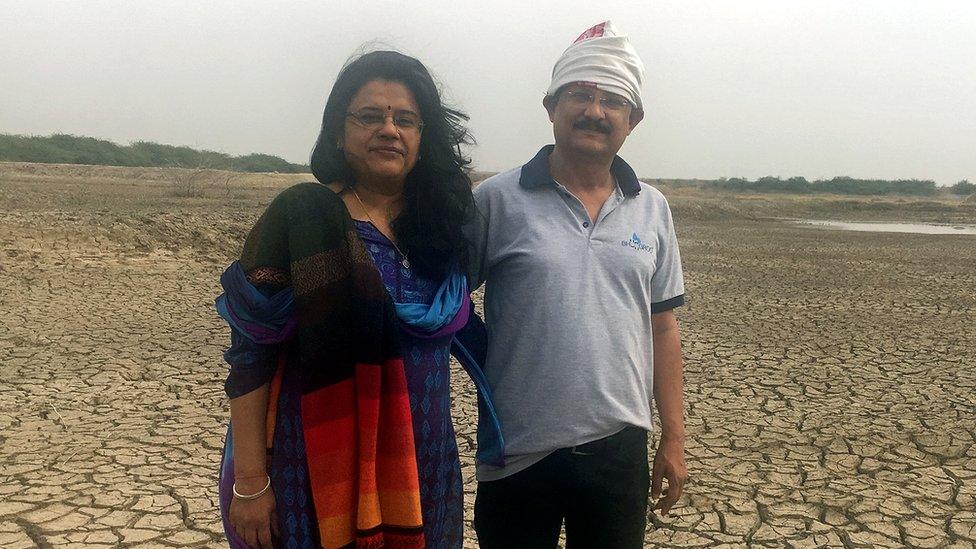

In India's desert state of Rajasthan, rural women are becoming the surprise agents of change, convincing coal-reliant communities to switch to solar.

They are called "Solar Sahelis" or "solar friends", and their job is to convince their neighbours to invest in solar-powered solutions.

But it's not easy. For decades, rural India has been flooded with poor quality solar products, most of which have ended up in landfill.

For the Solar Sahelis, their first hurdle is helping people to overcome their scepticism, that renewables are a failed technology.

Children studying by solar light at a night school in Ajmer, Rajasthan

With the fastest growing population on the planet, India's energy needs are staggering. Nearly a quarter of its population has no access to electricity, and for many others it's unreliable.

Ajaita Shah, a young Indian entrepreneur, saw this as an opportunity. In 2011, she founded the firm Frontier Markets, with the aim of selling reliable renewable products to those living off grid.

I meet Ms Shah in a rural village, just a few hours' drive from Rajasthan's capital Jaipur. Called the "sunshine state", Rajasthan has an average of 300-330 clear sunny days every year.

And that's the message of Frontier Markets - electricity maybe erratic, but sunlight is regular and reliable.

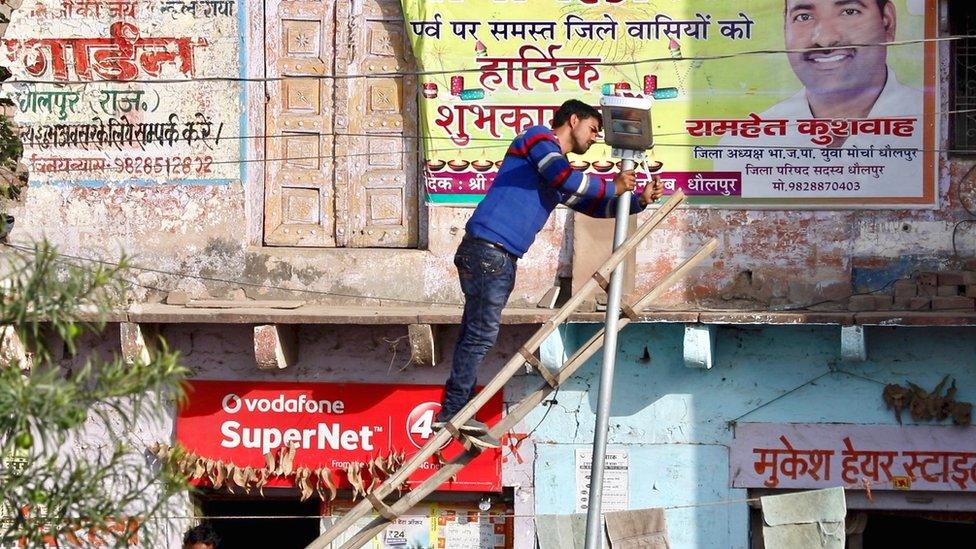

In this rural hamlet in Rajasthan, Frontier Markets is piloting solar streetlights in the hope of attracting investors

Ms Shah tells me the first five years were tough as she struggled to expand the business. But in the process she realised two things; that all products must be available within one mile of the consumer, something she calls "last mile distribution", and to grow new markets she needed a trusted messenger.

Ajaita begun training up local women as solar entrepreneurs. In just two years, she established a network of 1,000 Solar Sahelis across Rajasthan.

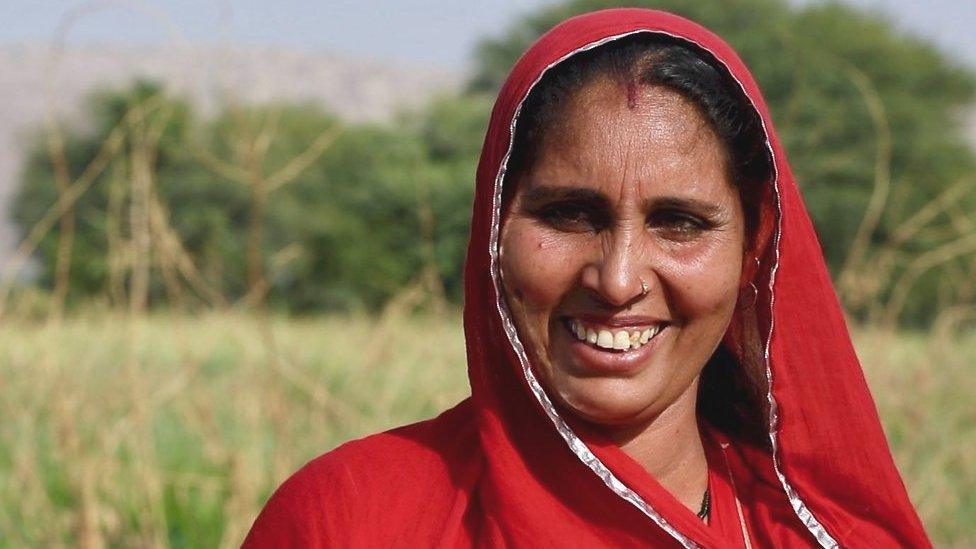

Santosh Kanwar is one of the Solar Sahelis

Travelling further into the state, I meet one of the Solar Sahelis, Santosh Kanwar.

Two prospective customers have dropped by her house. Drawing the curtains, Santosh begins her sales pitch in the dark, demonstrating a range of solar powered products, from tube lights to handheld lamps.

"It is not easy," she tells me. "We have to go to the villagers again and again to convince them".

"I have to explain to them that solar torches don't need electricity to recharge them, whereas re-chargeable battery-powered torches do. Unlike regular shopkeepers who give no guarantees, we also provide a prompt after-sales service."

Santosh Kanwar demonstrates different solar options to her customers in a home made dark room.

But are the Sahelis changing minds?

At the local market, I meet a group of farmers. The conversation quickly moves on to the poor state of the electricity supply and the problem of frequent power cuts.

I ask if they had heard of any solar alternatives?

"We use re-chargeable battery powered torches, but the electricity supply we need for these to work is not reliable. I've never heard of a solar-powered torch" says Hakim Singh.

A younger famer, Ashok Sharma, chips in, "I have heard of it, but such products are not available at our market."

For Ajaita Shah, the first hurdle is convincing people solar is a reliable alternative

Clearly, it is an uphill task. But Ajaita Shah is confident that investing in women is a smart business move, and the key to poverty alleviation and change.

"We recognise the value that women offer; communication, marketing, data collection, demonstrating and after-sale service" she says.

"These are key elements that these women are participating in, not just sales-driving."

Alongside selling solar products, the Sahelis are expected to fulfil their traditional duties, such as running the household and working on the land.

Unlike their male counterparts who frequently work away from the village, living and working locally means the Sahelis inherently know what villagers need, from domestic lighting at home to handheld torches for working in the fields at night.

The solar lamps are more expensive than battery powered alternatives, but come with a warranty and a weekly home service option by an engineer.

"This is about building a long-term relationship with the rural household", says Ms Shah.

"Today, if they buy a solar torch from me because they need it for outdoor lighting, because of the connection to the Saheli, she is helping us to understand that six months from now, they're going to need a poultry machine, 11 months from now they're going to need a home lighting system."

Ajaita's business model seems like a win-win solution, but a lot rests on the shoulders of the Solar Sahelis.

For many, earning a wage with commission on top is the first time they have played a part in their local economy.

But for Santosh Kanwar, its not just about the boost to her family's income, its also driving her confidence and ambition.

"Storing such expensive products at home, and people trusting my word when I sell them, it makes me feel responsible," she says. "I am earning money too, so I hope to set up a shop some day."

Santosh Kanwar pitching to prospective customers

Part of our series Taking the Temperature, which focuses on the battle against climate change and the people and ideas making a difference.

This BBC series was produced with funding from the Skoll Foundation.

Production team: Divya Arya and Aamir Peerzada

- Published8 June 2018

- Published1 June 2018

- Published25 May 2018

- Published18 May 2018

- Published11 May 2018

- Published16 May 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published20 April 2018