Farming underground in a fight against climate change

- Published

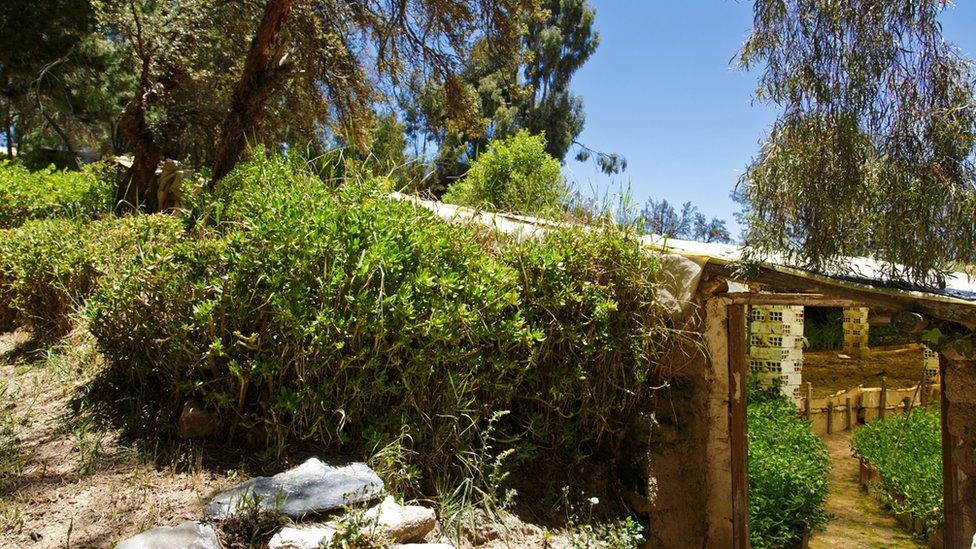

One of 18 Walipinis run by the Gemio family in El Alto, in the Bolivian highlands

The Andean Plateau or the Altiplano, is one of the largest and highest plateaus in the world. In order to protect their crops from drought, flash floods and increasing temperatures, Bolivian farmers are going underground.

Bolivia is among the nations least responsible for climate change, but one of the most vulnerable to its effects.

Almost 60% of Bolivian farmers live on the Altiplano, but it is a place of extremes, suffering from frequent drought, frost, high winds and radiation.

Following traditional farming methods, such as growing on terraced fields or using foot ploughs, makes crops vulnerable to erratic rains and erosion.

Gabriel Condo's Walipini is barely visible against the landscape of the Altiplano

In an effort to ensure food security for their families and livestock, some Bolivian farmers have built underground greenhouses, locally known as 'Walipinis'.

Growing underground

There is something a bit magical about Walipinis. With only their roofs visible, they are barely indistinguishable from the plateau's arid landscape.

But it's what's inside that counts.

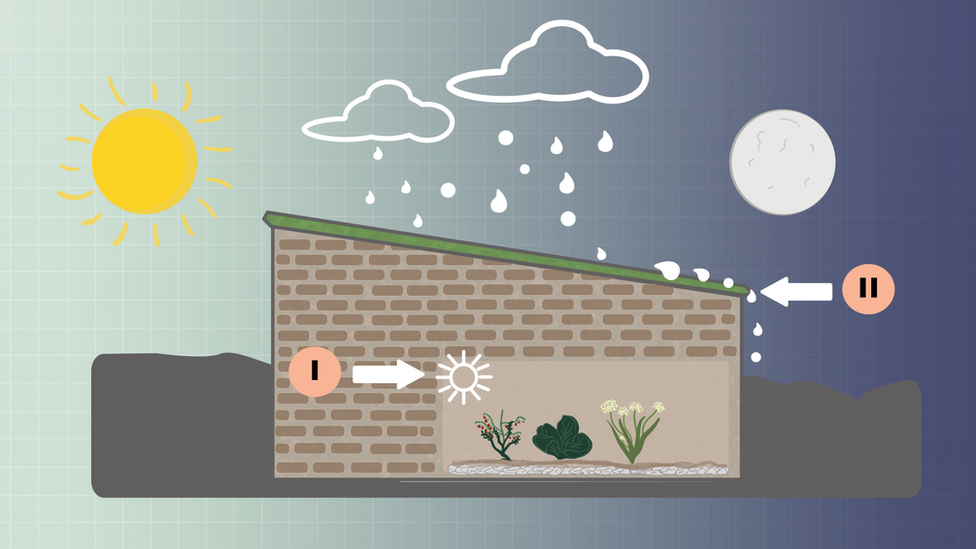

i) Bricks absorb and conduct heat from the sun, creating warm and humid conditions all year round ii) Walipinis are built to defend crops from the elements; including hail storms, flash floods, and burning heat

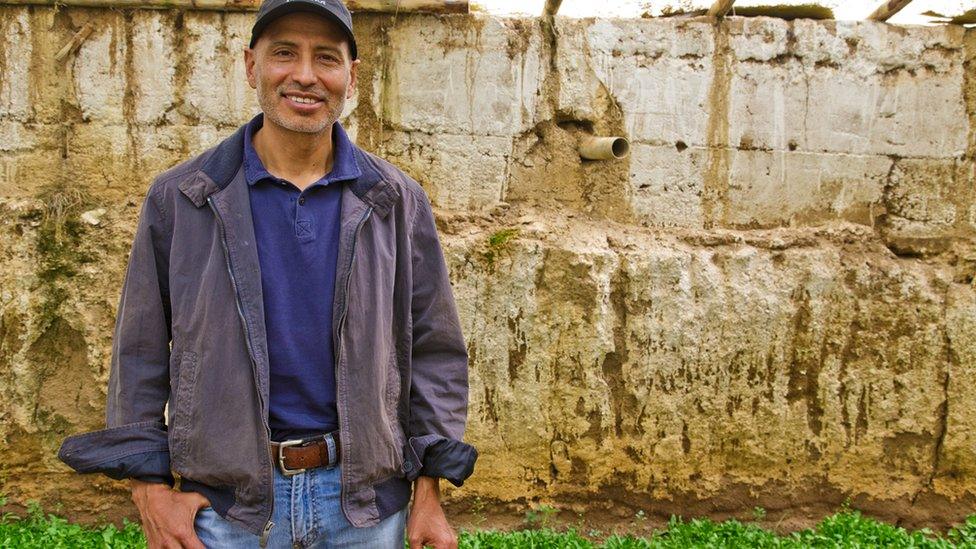

Farmer and llama breeder, Gabriel Condo Apaza built his Walipini two years ago. Cheap and simple, he tells me it's helped him to save money and improve the diet of his five children.

"We no longer buy vegetables in the market" says Condo, standing proudly next to his Walipini in a remote part of the Oruro region. "Now, we produce them here".

He tells me farming out in the open has become nearly impossible, due to increasing temperatures and erratic rainfall.

"Now, we can't even guess when is the right time to plant the potatoes. We try, but fail. The harvest frequently fails".

47 year old farmer and llama breeder, Gabriel Condo Apaza

The local Aymara name 'Walipini', translates as 'very well', because irrespective of the conditions outside, the Walipini maintains a stable microclimate inside.

However, this is not some ancient Andean agricultural practice, but a technology developed just 25 years ago by a Swiss volunteer, Peter Iselli.

Funded by a European development fund, Peter's mission was to explore new technologies that could ensure food security for this rural population.

However, shortly after achieving his mission, of developing his first fully functioning Walipini, Peter tragically took his own life.

His farm, along with his experimental Walipinis, were left to fall derelict.

Growing ivy on the walls help the Walipini to retain extra moisture

Farm 'For Sale' in the middle of nowhere

When businessman Michael Gemio's car broke down in the middle of nowhere, he sought help from an abandoned-looking farmhouse. The only sign of life was a "For Sale" sign out the front.

Little did he know at the time, that this would be the start of a remarkable journey for him and his family.

Despite lacking any agricultural experience, the Gemio family decided to buy the farm in the then remote area of El Alto.

They set to work, clearing out the numerous derelict structures scattered all over the farm. But it remained a mystery, what all these half built and buried buildings were for, until the neighbours came to visit.

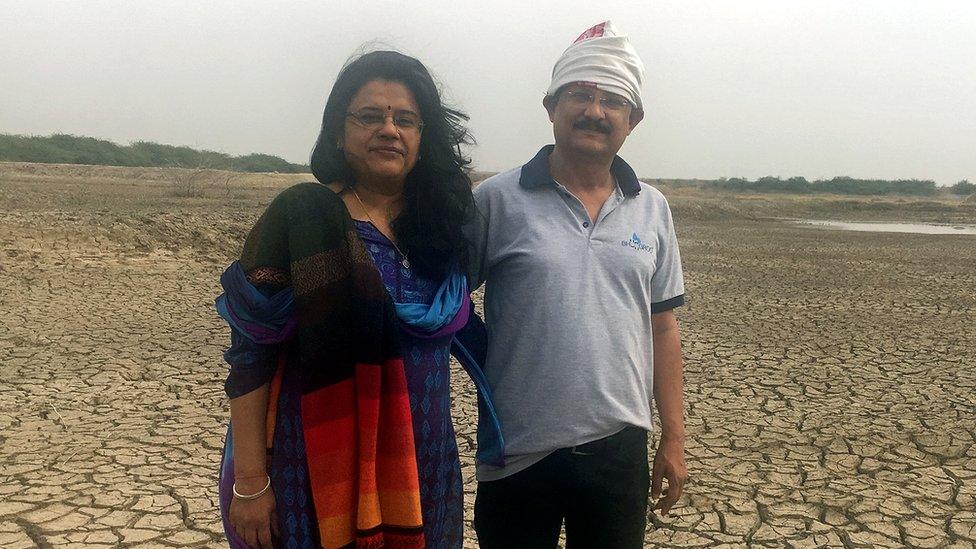

Michael and his family now run a large and successful eco-farm in El Alto including 18 Walipinis

Some of the local farming families had been recruited by Peter Iselli, who they endearingly called, El Suizo, "The Swiss", to help in the structural development of the technology.

Twenty years on, the Gemio family, with help from local agricultural engineer Héctor Vélez, have 18 working Walipinis on their farm; producing fruits, vegetables and salad leaves in abundance, whatever the weather.

And thanks to the success of the Gemio family eco-farm, the technology spread across the Altiplano, with neighbours helping each other to set up their own Walipinis.

The Gemio's neighbour, Héctor Vélez, is picking Valerianella Locusta, a type of lettuce known locally as 'The Swiss' after Peter Iselli the inventor of the Walipini

How to build a Walipini

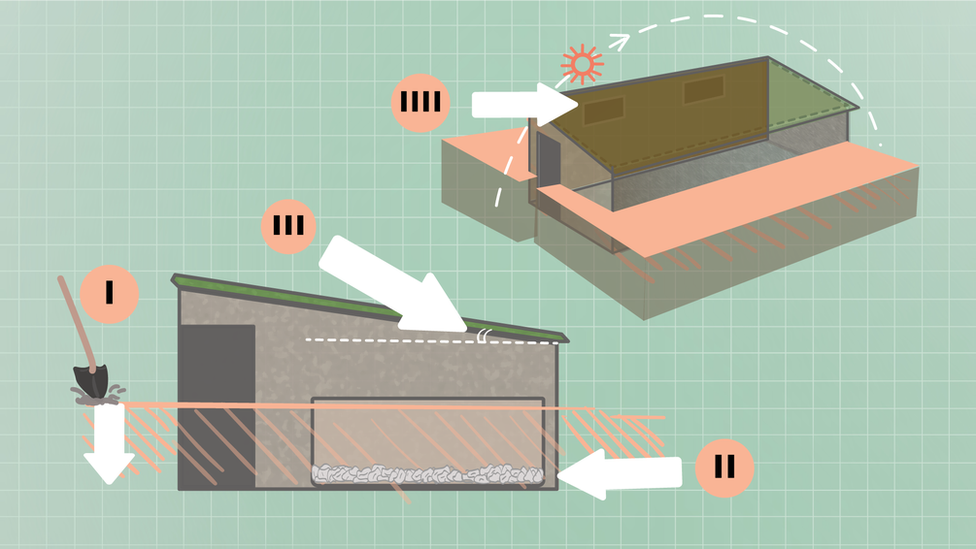

Compared to conventional greenhouses, Walipinis are considerably cheaper and more effective for this part of the world.

At 4000 metres above sea level, a regular greenhouse would not last long exposed to the strong winds and high UV radiation.

Excavating the site is labour intensive, but it's a long term investment.

i) Dig 1 metre deep ii) Fill it with stones for drainage iii) Build four brick walls, a door, and window for ventilation. Then lay a clear roof angled to 30 degrees iiii) Orientate the tallest wall to face south to absorb maximum sunshine throughout the day

Walipinis are also water efficient, but they still need a small supply.

Drought and rising temperatures are already driving people away from these Bolivian highlands.

Many rivers in the Altiplano have already dried up

However, for the Condo Apaza family, they still have access to a small stream that runs just above their land.

Their Walipini continues to provide enough greens for a breakfast chard omelette, or lunchtime vegetable soup.

Gabriel Condo's llamas have access to both food and water

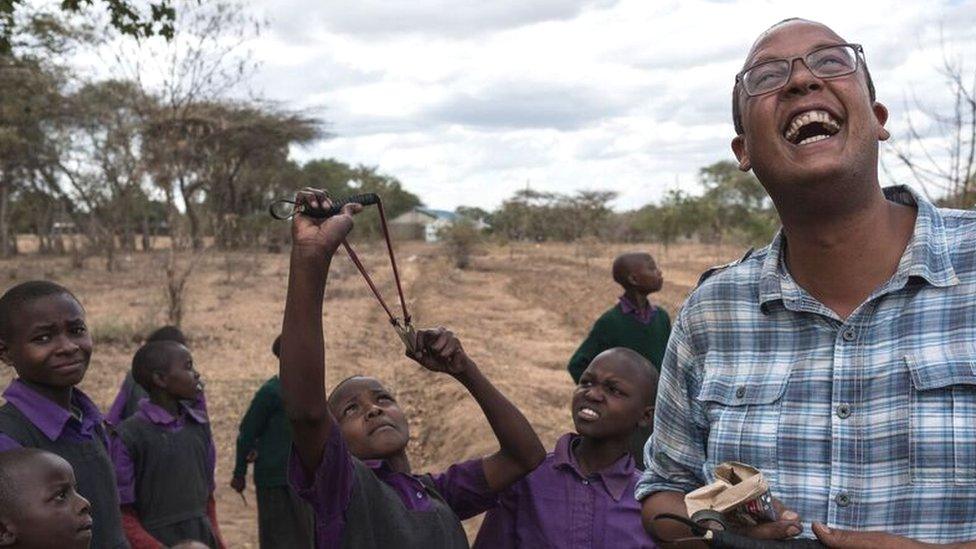

Part of our series Taking the Temperature, which focuses on the battle against climate change and the people and ideas making a difference.

This BBC series was produced with funding from the Skoll Foundation.

Photos: Inma Gil and Kelvin Brown / Illustrations: Jilla Dastmalchi

- Published8 June 2018

- Published1 June 2018

- Published25 May 2018

- Published18 May 2018

- Published11 May 2018

- Published16 May 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published20 April 2018