What should I do with my broken kettle?

- Published

Almost none of the kettles we can currently buy are designed to be repaired and re-used

My kettle, that has given sterling service for several years, appears to be hankering after retirement. It's a situation most of us are familiar with.

If not the kettle, you'll have found yourself with another appliance - an iron, blender, hairdryer or electric shaver - that's reached the end of its useful life; not to mention all the electronic devices we now have littering our homes, but what to do with them next?

I've turned my kettle upside down and there are screws holding together the metal and plastic components. I'm no engineer, so if it is going to come down to replacing the element, switch or wiring, I'm not sure I'm up to the job.

Plenty of small household appliances simply end up in landfill. In 2017, 525,000 tonnes of household appliances and equipment were collected as waste electrical and electronic equipment, external in the UK - but even when they are recycled, that usually involves crushing and melting and all you are left with is some low-value metals.

Many household appliances still simply end up as landfill

So I'm wondering whether there might be a way to avoid that.

Designers have already come up with clever ways to make it easy to take things apart, replace faulty components or, if beyond repair, ensure the materials can separate easily so they can go into the right recycling stream.

They've come up with screws that lose their thread when heated. There's furniture that can be slotted together and apart again. And snap-on casings avoid the need for glue.

While the approach - known broadly as "design for disassembly" - has been around for years, it isn't much in evidence when you browse the shop shelves for toasters and blenders. But it could now finally be ready to go mainstream, at least according to circular economy expert Sophie Thomas.

"Design for disassembly" is not common when you're looking for a new kettle or toaster

"I would say things are beginning to shift," she says, and points to the recent pushback against plastic. "Consumer pressure has created the space for brands to do something."

From 2013 to 2016 Ms Thomas oversaw "The Great Recovery" a UK-based project aimed at persuading policy makers, manufacturers and engineers to think about designing products in ways that would give them a longer useful life. Given that research and development take several years to come to fruition, she thinks the project's impact is probably starting to be felt.

Moreover, she says, the penny has now dropped that it's not just new designs that are needed, but a whole new relationship between manufacturers and customers, where the seller of the product takes responsibility for its longevity. And thanks to the internet, these days that new relationship is easier to create.

A handful of small companies are putting the concept into practice.

Gerrard Street's headphones are completely modular - if one bit fails it can be replaced

A few years ago Dorus Galama and Tom Leenders, both music lovers from Rotterdam, noticed that they were replacing their headphones two or three times a year. Good-quality headphones don't come cheap, but once a cable breaks or a headband snaps, they're good for nothing but the bin.

"It's almost impossible as a consumer to repair them, as everything is glued together. You can't get it open; you'll damage the product even more if you try," says Mr Galama.

"I had all these headphones in my closet with one component defective but the rest working perfectly," says Mr Galama.

So he and Mr Leenders set up a firm that sells fully modular headphone kits. You pay a monthly fee and if any component breaks, you order a replacement part. At first consumers were wary of getting locked into a subscription model, but they are now "getting used to the idea", he says.

Gerrard Street uses a subscription model to sell its headphones

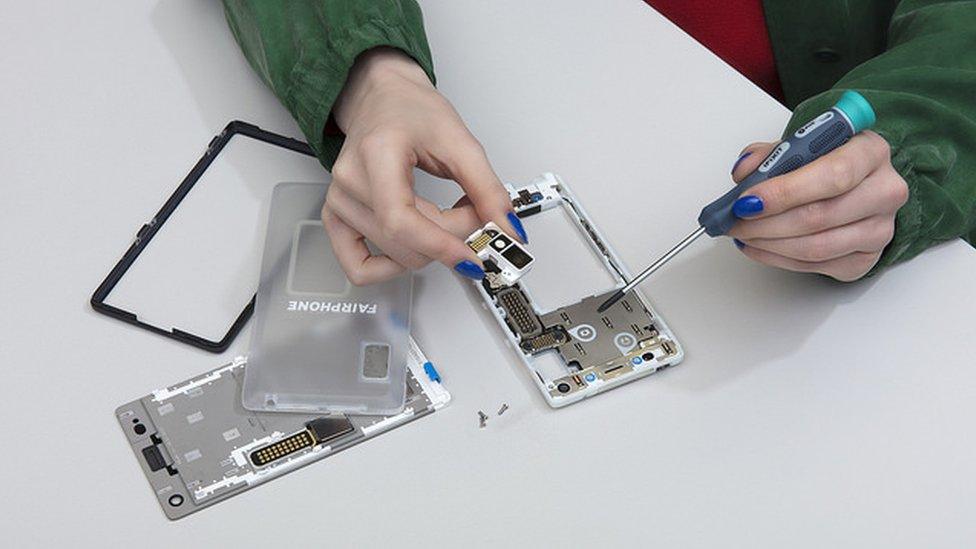

Gerrard Street is in its early days, but they have fellow Dutch pioneers Fairphone to look up to. The first mobile phone Amsterdam-based Fairphone produced focused on using ethically-sourced materials. But the second iteration was also modular - to ensure customers could change parts that failed or ones they just wanted to upgrade.

"The thinking behind it is if you prolong the use of the Fairphone, you end up using half as much resources," says the firm's spokesman, Fabian Huhne.

Fairphone, however, is very much the exception, he says, in an industry that is in general designing items that break easily and won't even let you take out the battery. And he says the approach is winning over customers, fed up with replacing their phone every two years.

Dutch firm Fairphone has pioneered a mobile phone that allows users to up-date it themselves

For firms who already have a continuing relationship with buyers, like business-to-business suppliers, design for disassembly makes even more sense.

Furniture-maker Orangebox, based in Wales, designed its modular "Do" office chair to be easy to put together, with snap-on and -off parts including the seat cushion, arms and fabric back. Orangebox maintains the chairs, changing damaged parts, and they're also much easier to transport.

But what about household appliances? Sophie Thomas says the biggest obstacle is the low value of the materials involved. A toaster is effectively "filaments and breadcrumbs" when it is recycled - offering manufacturers very little financial incentive to set up a system so they can reuse or recover the parts.

Circular Economy

The BBC's Circular Economy series highlights the ways we are designing systems to reduce the waste modern society generates, by reusing and repurposing products.

Yet while my Dualit jug kettle is sadly destined for the crusher, when I call to check what to do with it, I find the firm does take seriously the idea of designing for disassembly.

Dualit has been making repairable toasters since 1952. Customers can take them apart and slot in a new element when required. One customer reported they'd kept theirs working for 40 years - which is just as well, as it costs four times as much as an ordinary toaster.

More recently Dualit has started selling what it says is the only patented repairable kettle on the market. (The repair does need to be done by qualified technicians, however - it's not a DIY job).

Customers can replace the heating elements in their Dualit toasters when they go wrong

"A lot more work goes into assembling these products," points out Alex Gort-Barten, in charge of engineering at Dualit, which is why these models cost more.

But it's part of the firm's philosophy, he says.

"It's just good engineering and good engineering involves leaving little waste. If a product is well engineered, then part of that process is to look beyond the time of purchase; making it easy to disassemble so it can be repaired, or if it's at the end of its life, easily taken apart so the components can be recycled."

Disassembly is a principle the firm is trying to apply across more of its products. It has developed a snap-fit solution for the casings on hand blenders and mixers that allows them to be repaired.

And even if items can't be repaired, they're designed in a way - using screws and washers and bolts to hold them together - that means some materials can be recovered and separated for recycling.

But it's only a small proportion of products that end up back in Dualit's hands. They don't collect items like my kettle - I've asked. It can't easily be taken apart - and still has to go to the tip.