The rise and fall of a business colossus

- Published

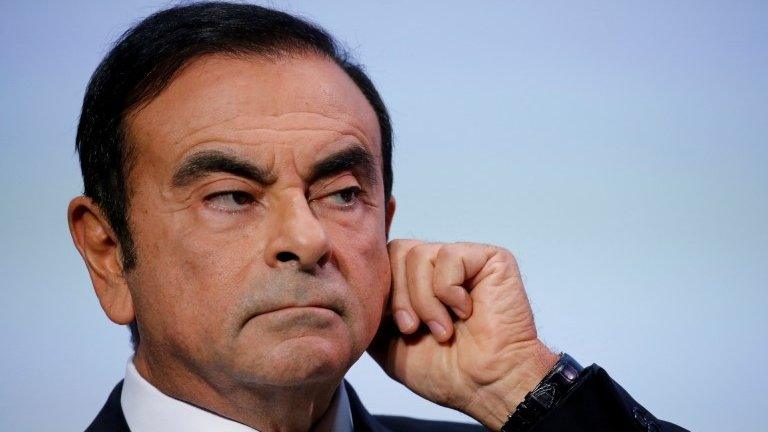

It's hard to overstate the stature of Carlos Ghosn - and not just in the car-making world.

His position atop an empire comprising three of the world's biggest manufacturers - Nissan, Renault and Mitsubishi - made him the leader of a trailblazing global alliance. He is/was one of the most influential and powerful business leaders anywhere in the world.

His downfall comes as a big shock. He was well known and widely liked by journalists mainly thanks to his generosity with his time and his habit of making headline-grabbing comments - like a Jose Mourinho of business leaders.

Carlos Ghosn was both a business visionary and - it now seems - a traditional character in a very familiar business fable.

An alliance between three global manufacturers was something not seen before in the car industry and was his personal creation. Saving a beleaguered Nissan and teaming it up with a European giant like Renault was arguably something only he - a French citizen (Brazilian birth and Lebanese descent) who saved Japan's treasured Nissan could have done.

Electric car party

Although known as "le cost killer" his easy cross-cultural charm was able to build a bridge between two manufacturers who were (and many will tell you still are) naturally suspicious of each other.

After adding Mistubishi as the third leg of the stool, the alliance he built now produced 10 million cars last year putting it behind only Volkswagen as a volume manufacturer.

With his superstar status assured he had the licence to make bold moves. He was very early to the electric car party - evangelising about their imminent surge and putting his money where his mouth was by investing heavily in the technology despite a sceptical motoring press.

Except it wasn't his money. It was Nissan's money. The same money that reportedly bought him four houses dotted around the world for his personal use only at a cost of £15m.

Sun Kings and scandals

It is in that regard he also embodies another important business phenomenon - the classic tale of the boss-turned-emperor.

"L'etat c'est moi" said Louis XIV. In their own ways, and to greatly varying extents, so have other long serving chief executives. Lord Browne who led BP for 12 years and masterminded the megamerger with US giant Amoco was called "the Sun King" by employees. His reign ended after controversy surrounding his private life.

Sir Martin Sorrell who turned a shopping basket company into a £20bn media giant stood down after 33 years amid claims, which he denies, that he spent company money on personal activities.

These leaders are not nearly as dastardly as Mirror Group's Sir Robert Maxwell or Polly Peck's Asil Nadir - both of whom stole millions from the companies they founded.

But they tell a familiar story of the feted, long-serving boss for whom the board meant to control them became toothless and irrelevant as the lines between the company and the individual became blurred.

Breeding frustration

So what's the answer?

The US political system has decided that term limits are the answer to stop the president becoming imperial. Although some organisations, like Deloitte, do impose time limits on their chief executive and chair roles (at Deloitte's, those roles are limited to two consecutive four-year terms) - these are generally used in partnerships where the chief executive role is very different to that in a publicly listed company.

Maybe there is no way to alter this age old trajectory. Success breeds confidence as the boss think that the success is entirely down to them, which breeds intolerance of other views, that breeds resentment which prompts frustrated subordinates and whistle-blowers to look for misconduct, which creates a scandal, which ruins legacies - as this one threatens to do to Carlos Ghosn.

As he once said himself. "If you have not been a villain at a certain point in time, you will never be a hero. And the day you are a hero, you may become a villain the next day."

- Published20 November 2018

- Published31 December 2019