2018 'worst year for US school shootings'

- Published

A Los Angeles high school holds a drill to prepare for the threat of attacks

This year, 113 people have been killed or injured in school shootings in the United States.

That's the sobering finding of a project to count the annual toll of gun attacks in schools.

At the beginning of 2018, Education Week, a journal covering education in the US, began to track school shootings, external - and has since recorded 23 incidents where there were deaths or injuries.

With many parts of the US having about 180 school days per year, it means, on average, a shooting once every eight school days.

Another database recording school shootings says 2018 has had the highest number of incidents ever recorded, in figures going back to 1970.

That database, from the US Center for Homeland Defense and Security and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (Fema), uses a different way of identifying gun incidents in school, and says this year there have been 94.

Never 'normal'

The idea behind the year-long Education Week project was to mark each shooting - so that attacks should never come to seem "normal" and that every victim should be remembered.

But it was also an attempt to fill in the gaps in knowledge, because while there was intense media coverage of multiple-casualty shootings, there was much less clarity about the attacks happening across the country each month.

Mourning in the wake of the shooting at a school in Parkland, Florida, in which 17 people were killed

Lesli Maxwell, assistant managing editor of Education Week, said this year has "definitely been an outlier" with two large-scale school shootings, which have contributed to such a high annual loss of life.

Seventeen people were killed at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

At Santa Fe High School near Houston, Texas, there were 10 killed, with both gun attacks carried out by teenage boys.

"This year also stands out because of all the activism that followed Parkland, with students leading the charge," says Ms Maxwell.

Teenagers, guns and victims

There have been campaigns for tighter gun control - and on the other side of the debate, calls for more weapons in the hands of teachers or school staff.

While such mass shootings made headlines around the world, the majority passed by with much less attention.

Francine Wheeler, mother of a Sandy Hook shooting victim, at a rally against gun violence in schools this summer

These included a shooting at a primary school in Virginia last month, when a parent collecting their child was shot in the leg when a gun in the pocket of another parent was accidentally fired.

Or in March in a high school in Maryland, when a 17-year-old teenager shot and injured two students and then, after he was confronted, killed himself. One of the injured, a 16-year-old girl, died a few days later.

The shootings are a bleak list of teenagers, guns and innocent victims. The perpetrators are as young as 12 but are mostly 16 or 17.

The lack of certainty about the number of school shootings is also because it can be defined in different ways.

Highest level

The Education Week tracker only counted events where there were casualties and where shootings took place on school property and in school time and where there was a victim other than the perpetrator.

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security has a different measure - counting gun incidents in school, regardless of the time or whether anyone was shot or injured.

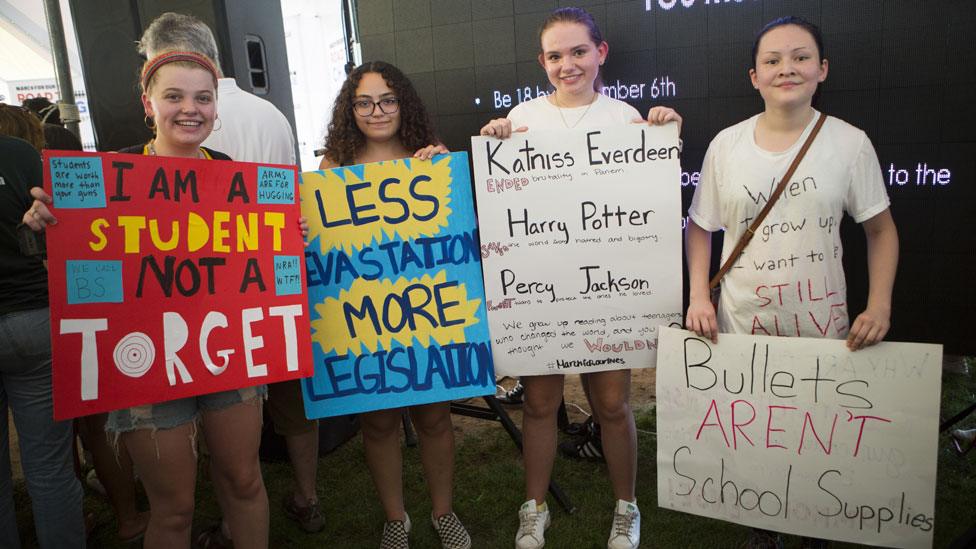

Students have been campaigning for action to stop school shootings

This wider measure has so far recorded 94 school shooting incidents across the US - which stands significantly above what had been the previous highest total, 59 in 2006.

By this measure, 2018 has also been the worst year for deaths and injuries, with 163 casualties, compared with a previous high of 97 in 1986.

It also shows the big increase over the decades, with annual casualties in the 1970s never higher than 35, about a fifth of this year's level.

Killers typically 17 and male

The data from five decades of school shootings shows the most typical age for a school killer is 16 or 17 and these perpetrators are highly likely to be male.

The attacks are not often "indiscriminate", but are more usually an "escalation of a dispute" or a gang-related incident.

An "active shooter drill" in a Montana school

But as well as following the statistics of school shootings, Ms Maxwell has seen the aftermath.

In the schools affected by such attacks, she says, there can be a cycle of strong and contradictory emotions.

At first, along with the "raw grieving" there can be a "coming together" of communities.

But that can be followed by divisions and a "splintering" as families look for answers and people to hold accountable for their loss.

She says there can be "fury against authorities and institutions", rather than any consensus on what should happen next.

No consensus

There is also no agreement at a national level about how to respond to school shootings, with opinion just as divided as when the year began.

"The needle hasn't moved," she says.

There are calls for guns to be kept out of schools and others calling for more guns to be used to defend schools.

"Our sense is that a vast majority of teachers don't want to be armed," she says.

"Whether it's one child or 17, it's awful and tragic and we need vigorous discussion about how to put a stop to it," says Ms Maxwell.

But there is no sign of any agreement about how that might happen.

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is Sean Coughlan (sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk).