Do your children have a balanced diet of play?

- Published

Can toys help children express themselves?

Two generations: parents and youngsters. One is tech-obsessed, with a short attention span, who find it difficult to talk about their emotions. The other is their children.

Whatever their own addiction to social media or the demands of day-to-day life, parents are desperate for their sons and daughters to have a more balanced approach to life. They want them to spend less time tucked behind a screen on their own, and more out and about playing with friends or enjoying the board game they were bought for Christmas.

These demands, not always backed up with research, have been noted and developed by schools, many of which run mindfulness sessions for even the youngest children, helping them to settle down ready to learn after whizzing around the playground.

They have also been seized on by toy manufacturers, for whom staying calm may carry on profit making.

"Anything that encourages emotional play should be valued," says Natasha Crookes from the British Toy and Hobby Association (BTHA), who says mindfulness is an emerging theme in the sector.

"It can help children to sleep better and discuss their emotions more."

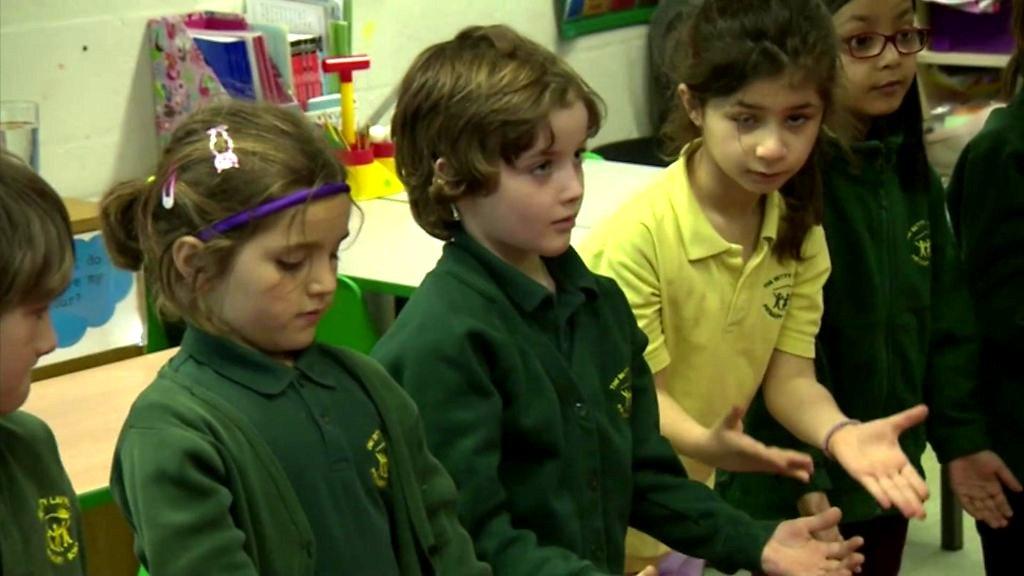

Mindfulness is being used to help children's mental wellbeing in schools.

New toys aimed at this market could be found this week on the fringes of the BTHA's Toy Fair in London's Olympia - the UK's biggest toy industry trade fair.

On the smaller stalls, beside the global giants promoting licensed film spin-off toys and games, were people like Fernando Del Rio of Magic Box Toys.

He was there to show off Moji Pops - new pocket money collectable characters, being launched in the UK this March. The face on each figure swivels to reveal one of 12 different expressions.

Moji Pops are the latest in the collectable craze

"It is all about emotions and making it easy for children to express them," he says.

The aim is to encourage youngsters to talk about how they are feeling and create stories using the characters in front of them. The target audience is aged between four and eight.

How to be more mindful

Notice the everyday - engage your senses, for example to think about the food you eat and the feeling of the air moving past as you walk

Choose a regular time for your practice, for example during your morning commute or on a lunchtime walk

Try seeing things from a different perspective. This can be as simple as choosing a different seat at school, college or in a work meeting, or going somewhere new for lunch

Watch your thoughts - see them as "mental events" and let them come and go in your mind, like buses

Name your thoughts and feelings to get more awareness, for example recognising "this is anxiety"

As well as practising in your day-to-day life, you can set aside time for mindfulness meditation, yoga or tai-chi

Source: NHS

On a nearby stall is Chris Carpenter, a geophysicist turned game-maker, with his decks of cards that engage the brain without children realising they are educational.

These card games are designed to keep players involved

One pack - a cross between snap and tic-tac-toe - allows all the young players to be involved in the game at the same time, without waiting for their turn. Another is a game with no rules.

Some youngsters are faster than their parents, he says, as we shut off parts of our brain as we age.

All of this is designed to extend attention spans, against a backdrop of children's TV in which episodes are shortening, sharing on social media is instantly gratifying, and games can be called up in a second on a smartphone.

In fact, only 1% of toys are "connected" devices and one expert says the best advice for parents is to give their children "a balanced diet of play" including digital, imaginative and cognitive tasks rather than imposing bans on certain activities.

"There is a place for all kinds of play in a moderate and balanced approach. Parents should not demonise screens," says Dr Amanda Gummer, founder of research consultancy Fundamentally Children.

She argues that children should not be left to solitary, sedentary, passive activities, but also says parents who schedule certain types of play at certain times may find it counterproductive.

Some regard mindfulness as a "silver bullet", she says, but she argues that a better approach is to ensure children are immersed in slow toys or activities.

"Our brain needs time to consolidate," she says. So, everyone needs to make the most of "natural opportunities" to slow down. That could be anything from walking to school or carrying out a repetitive household chore, to reading and modelling.

Junko launched in December to seize on the reusable trend

That will be music to the ears of Peter Rope, a graphic designer and the creator of Junko, which sells packs of accessories to make junk modelling into cars and boats. The packs contain wheels, chassis, and paddles, all made in the UK out of recycled plastic from children's suitcases, which then attach to junk models.

It was launched just before Christmas and inspired by making models with his own children and coming up short when trying to find working wheels.

"It puts creativity first. We think it will inspire a whole afternoon's play, then children will return the next day to paint them," says Mr Rope.

Toys that guarantee half a day's entertainment, stimulate children's imaginations, and avoid dumping more plastic on the world hits all the buttons of an environmentally conscious, time-pressed, modern parent.

Now all they need to do is get the kids off their phones.

- Published23 January 2019

- Published29 August 2018

- Published24 February 2017

- Published10 October 2018