The vegan leather brewed in a lab

- Published

Andras Forgacs was eating a steak in China when he came up with his business idea

As soon as I meet Andras Forgacs we head outside into the freezing cold of Davos. Naturally he reaches for his coat, but I am slightly surprised at what he pulls out - it's just a normal, black puffer jacket.

As the founder and chief executive of a start-up firm that has created a vegan alternative to leather, I expected him to be wearing a coat made out of his own material.

In reality it's a bit too soon for that. Modern Meadow, the company he set up eight years ago, is still producing the fabric he has designed only in small quantities.

Nonetheless, in the same way that the rapid growth in the popularity of vegan food - from hamburgers to sausage rolls and chicken alternatives - has shaken up the food industry, he believes his firm can help do the same to the $200bn (£153bn) leather industry, external.

"It's a massive market with massive shortcomings. You have to raise an animal in a field using up water, gas and creating greenhouse emissions and then transfer the hide half way around the world."

Fur clad figures are a common sight in Davos

Apart from the environmental harm, there is huge wastage in the industry. Up to half of a cow-hide can be wasted due to imperfections such as bites.

With alligator and crocodile skin, he says it's even worse, with up to 90% of the material wasted because of the need for a perfect pattern.

Business consulting firm Grand View Research (GVR) has predicted the global faux leather market will hit $85bn by 2025.

It cites the lower cost of producing animal-free products along with the increasing number of consumers opting for animal-free materials.

"As textile technology is evolving consumers are preferring vegan fashion," it said.

Permanent display

Mr Forgacs says the first product made from the material will be launched this year, but refuses to say what it will be.

Instead, like a travelling car salesman showing off his wares he pulls out several samples from a folder he is carrying around with him.

The pieces vary in colour, thickness and texture but share one key thing in common - no cow was killed in their creation.

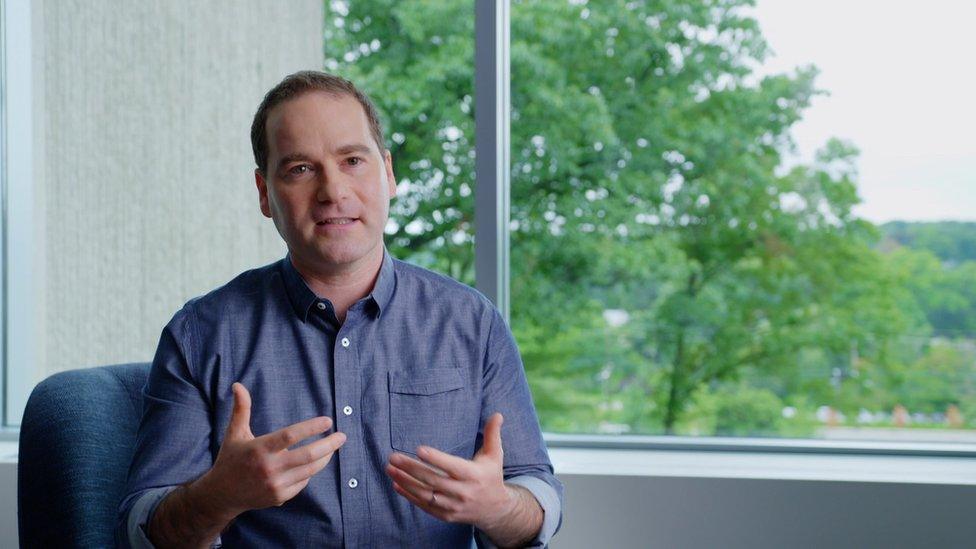

The product is created from yeast cells that are fermented in a similar way to beer to create collagen, the protein that gives skin its strength and elasticity. From here the collagen is purified and assembled into unique material structures that can be adapted in various ways depending on its purpose.

A T-shirt made using the new material, called Zoa, was commissioned and acquired to the permanent collection by the Museum of Modern Art in New York as an example of the future of fashion, but Mr Forgacs says his firm is targeting more than just the fashion industry.

Eventually, he expects the fabric to be used for a variety of purposes, including clothing, shoes, handbags, car and plane interiors and furniture.

A T-shirt made from the fabric is on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York

Mr Forgacs is confident there will be demand for it, particularly from luxury brands seeking out alternatives to animal products amid growing consumer interest.

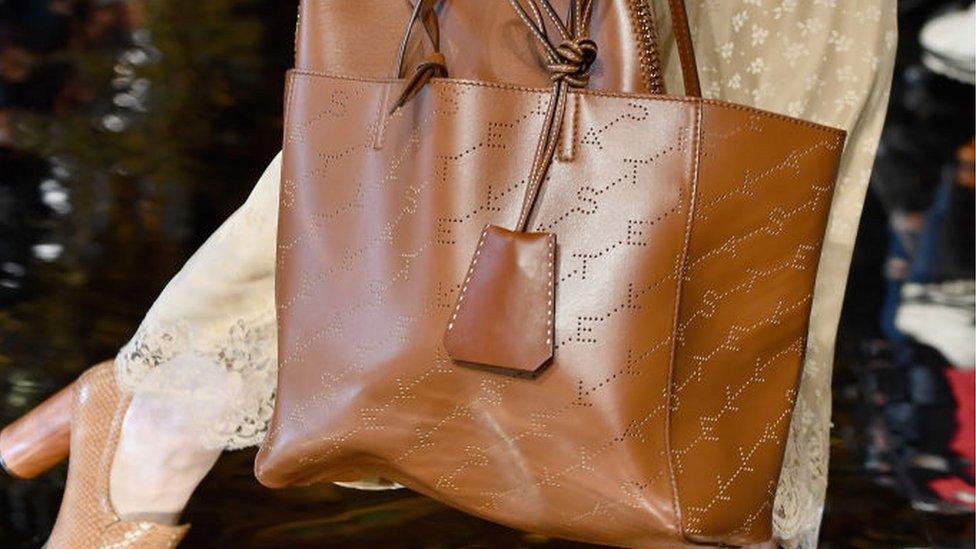

Well-known designer brands including LVMH, Furla and Michael Kors have already started substituting fur and leather with alternative animal-friendly materials.

Stella McCartney has gone further, with her brand shifting to "vegan fashion", using fungi instead of leather, and replacing silk with yeast proteins.

It's a trend that seems to have escaped the gathering of political leaders and company bosses at the World Economic Forum, many of whom are decked out from head to toe in fur to ward off the cold.

But Mr Forgacs says it's unrealistic to expect people to change their habits.

Stella McCartney has never used leather or fur in her designs

He believes presenting a viable alternative to such a common and popular fabric like leather is an easier way to drive change.

"It's hard to forsake what you love. If you can do what you love and still not harm the planet, that's better," he says.

In fact, it was while he was tucking into an imported steak while living in China that he had the idea for the company.

"It's one thing to read about it and another to live it. I just saw firsthand the explosion in consumption and the shift from an export-driven economy to a more affluent class," he says.

'Warmth and softness'

His ambitious aim is not only to imitate leather but to improve on it.

"We're using the aspects of leather such as its warmth and softness, but looking at how to make it better, more durable, more lightweight, more breathable."

The fact that they are creating the material - instead of taking it off a cow - means they can vary it however they like, creating different shapes, sizes and thicknesses depending on its purpose.

"With traditional material, you get what you get from the back of the animal and that's it," he says.

This is Mr Forgacs' third start-up firm. He has launched all of them with his physicist father and all of them are science-based.

While his background is in finance and he previously worked on Wall Street and in venture capital, he says his scientist parents instilled in him a love of science and the environment.

The material's flexibility means it can be adapted to suit the product it is being used for

His first firm was called Organovo and used 3D printing to create human tissue that could be used for medical research.

"As we developed that technology, other adjacent opportunities built up. If you can make skin you can make leather, if you can make muscle you can make meat," he says.

Initially, Modern Meadow focused on creating both vegan food and the leather-like material, but Mr Forgacs eventually decided the industries were simply too different.

As a result, the food technology was spun out to a separate business called Forke & Goode, and Modern Meadow's sole focus now is on creating alternative vegan materials.

Will we start to see people using products made from his material soon? He is adamant that we will.

While the company currently employs 90 people, it has now partnered with a firm to brew its yeast in large quantities.

But don't expect to see clothes made from it in a High Street shop near you any time soon. "It's not enough to support a Black Friday holiday shopping spree, we'll have to build up to that," he says.

But perhaps it's enough to make sure that when he next returns to Davos, he'll be wearing a coat made out of his own vegan material.

- Published24 January 2019

- Published23 January 2019

- Published23 January 2019

- Published22 January 2019

- Published23 January 2019

- Published23 January 2019