Tracking sanctions-busting ships on the high seas

- Published

Satellites can now track ships that turn off their Automatic Identification System

For a long time, being out at sea meant being out of sight and out of reach.

And all kinds of shenanigans went on as a result - countries secretly selling oil and other goods to countries they're not supposed to under international sanctions rules, for example, not to mention piracy and kidnapping.

The problem is that captains can easily switch off the current way of tracking ships, called the Automatic Identification System (AIS), hiding their location.

But now thousands of surveillance satellites have been launched into space, and artificial intelligence (AI) is being applied to the images they take.

There's no longer anywhere for such ships to hide.

Samir Madani, co-founder of TankerTrackers.com, says his firm's satellite imagery analysis has identified Iranian tankers moving in and out of port, despite US sanctions restricting much of the country's oil exports.

He's watched North Korea - which is limited by international rules to 500,000 barrels of refined oil every year - taking delivery of fuel via ship-to-ship transfers on the open ocean.

North Korea has been called out for evading UN sanctions

Turning off the AIS transponders that broadcast a ship's position, course and speed, is no longer a guarantee of anonymity.

His firm can even ascertain what cargo a ship is carrying - and how much - just by looking at its shadow on the water, says Mr Madani.

The fuller the vessel is, the lower it sits in the water, and this affects the size of the shadow depending on the sun's position at the time.

"There are some other indicators we don't want to mention - we have our own methods," he adds mysteriously.

Planet Labs - a private space firm that has launched 331 satellites over the last four years, the largest such fleet ever deployed commercially - offers ship tracking as a service to clients such as TankerTrackers.

As well as spotting nefarious maritime activities, these spies in the sky can give us a snapshot of the global economy.

Satellites can spot tankers undergoing - sometimes illegal - ship-to-ship fuel transfers

For example, Mr Madani has witnessed huge numbers of tankers sailing from the US to China suddenly stop mid-ocean, as trade tensions between the two countries peaked.

And now that Saudi Arabia, along with its Opec allies, has agreed to cut oil production in a bid to boost prices - much to President Trump's annoyance - traders can see if it is keeping its promise simply by monitoring the number of tankers leaving its ports.

In a bygone era, traders would have to have waited weeks to confirm that deliveries were falling.

Satellite tracking is giving traders near real-time data on where oil supplies are located, how much there is, and how long it will take to arrive. This means they can respond much more quickly to sudden shifts in price and demand.

A satellite snaps a tanker that has turned off its AIS tracking system off the coast of Egypt

Say a big winter storm hits the US east coast and the price of oil spikes as a result. Fuel tankers already en route to Europe, say, will sometimes "reverse course and head back across the Atlantic on the basis of the price", explains Michelle Wiese Bockmann, an independent shipping analyst.

Their cargoes will have been re-sold while in transit.

"When I first started tracking ships five years ago, it was by no means as evolved as it is now," says Ms Bockmann.

Vortexa is one of a new breed of companies applying AI to all this satellite and market data to monitor global energy markets.

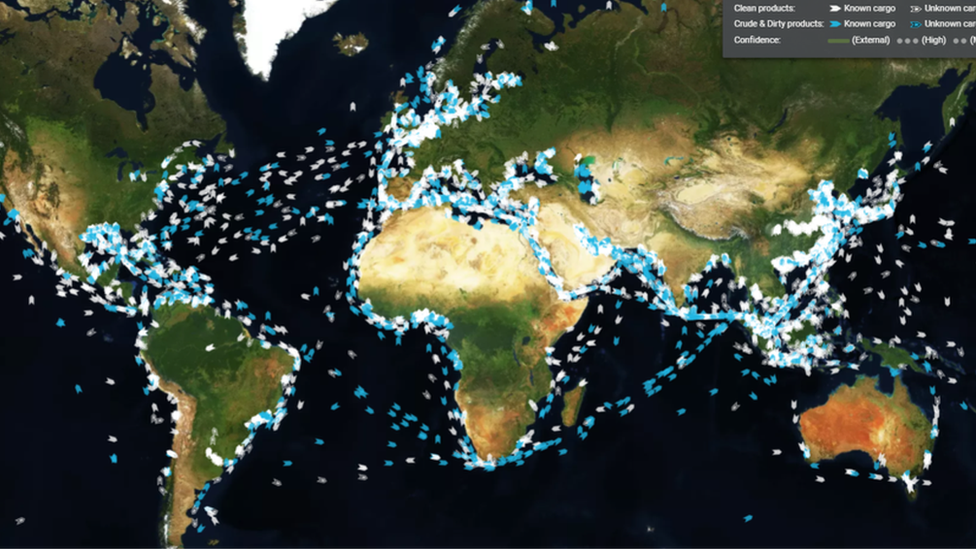

Fabio Kuhn, co-founder and chief executive, shows me a live map plotting the location of thousands of tanker ships across the globe.

There can be more than 5,000 tankers plying the world's oceans at any one time

Click on one and you see details of what it's carrying and where it's headed. There are also separate screens showing, for instance, all of the known diesel shipments heading towards the UK right now - useful to know if you expect cold weather to hit in the coming weeks.

"A company like ours could not have existed before 2015," he tells me. "There was not enough data for us to understand what is inside the tankers."

Even though Vortexa can't be certain of the cargo in every case, having so much data on ships and port activity means it can make automated guesses.

"It feels as if vessel-tracking has become a much more prominent element of the global commodity market," says Matthew Smith at ship-tracking firm ClipperData, "simply because it's giving greater transparency into what's happening."

His firm has mapped "every single dock in every single port" worldwide, and has logged every publicly available record of what cargoes have been loaded there. This means that if a ship with unknown cargo uses one of these docks, his team can make a good guess as to what it's carrying.

And as the ebb and flow of commodities trading affects the wider global economy, financial traders at big banks and hedge funds also want to keep an eye on shipping activity, says Mr Smith.

As ever, knowledge is power, and increasingly sophisticated satellites and data analysis are helping to deliver both.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external