'How a smartphone saved my mother's life'

- Published

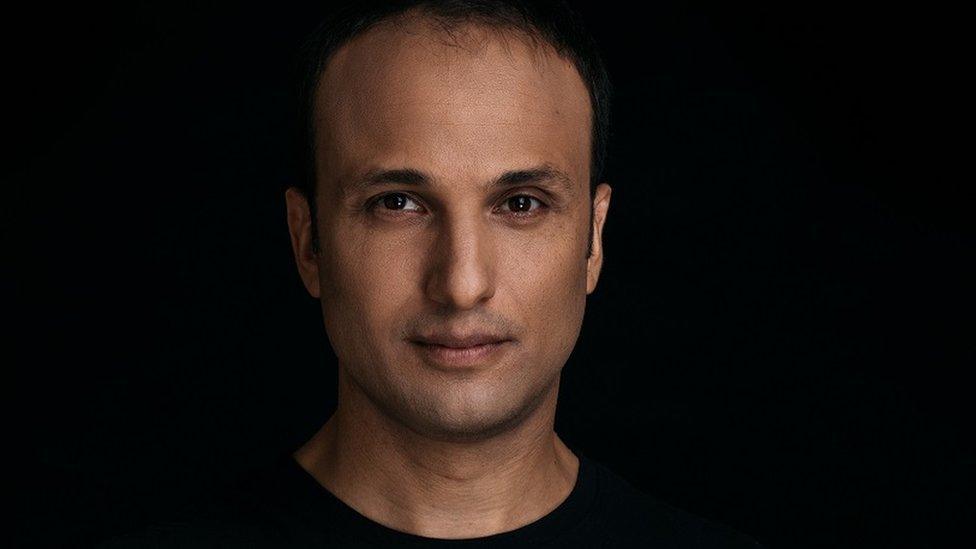

Entrepreneur Yonatan Adiri believes medical diagnosis by smartphone will be a huge market

As the smartphone falls in price while its capabilities improve, it is becoming a valuable tool in the diagnosis of a growing number of diseases and ailments around the world.

When Yonatan Adiri's mother fell down a bank and briefly lost consciousness when travelling in China, an initial diagnosis suggested she had a few broken ribs, but nothing more serious. Doctors were keen to fly her to Hong Kong for treatment.

But Yonatan's father was worried and took photos of the CT [computerised tomography] scans of the injuries, emailing them to his son. Yonatan showed the images to a trauma doctor, who instantly diagnosed a punctured lung. The flight to Hong Kong might have killed her.

"Who knows what would've happened if he hadn't taken photos?" Yonatan wonders.

The experience inspired the Israeli entrepreneur - formerly Israel's chief technology officer under the late President Shimon Peres - to explore how the smartphone could be developed into a medical grade diagnostic tool.

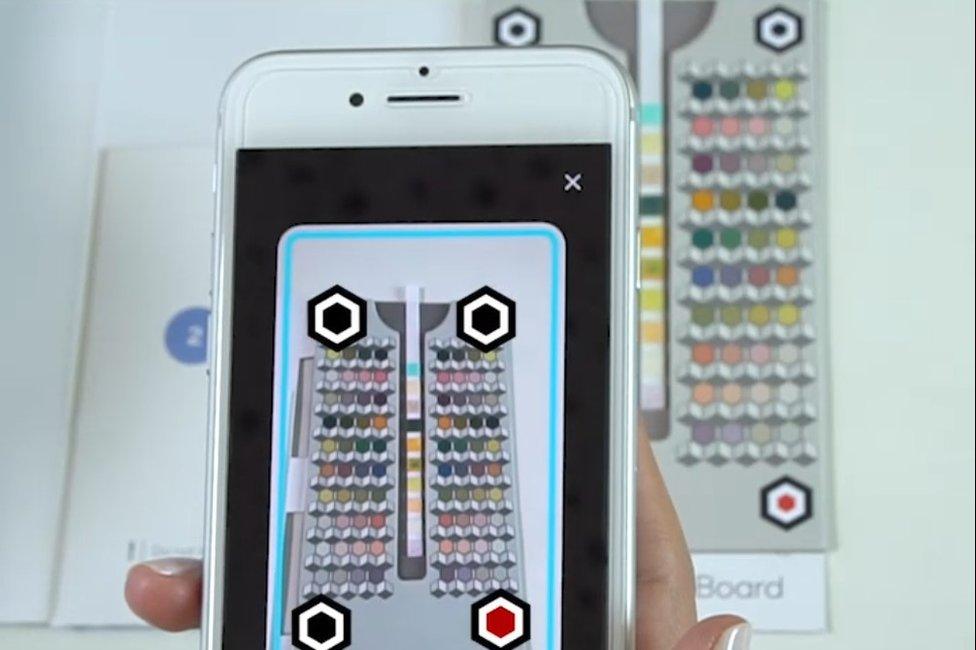

Healthy.io's urine test kit and app has been given regulatory approval

The result was Healthy.io, a start-up pioneering "medical selfies", as he calls them. The first product is a urine test kit that screens for signs of urinary tract infection, diabetes, and kidney disease.

The standard urine test involves a special dipstick featuring 10 tiny pads that change colour if they detect various substances, such as blood, sugars or proteins, in the urine sample. Normally a trained clinician analyses the colour changes by eye, but Healthy.io's smartphone app can do it equally well using its computer vision algorithm.

A smartphone chatbot called Emily takes people through the process step-by-step using voice, text and video.

The patient slots the dipstick into a colour-coded cardboard frame then scans the whole thing with the phone. The image is sent to the cloud for analysis and the results go to the patient's doctor.

"It's not a wellness device, it's a medical device," says Mr Adiri, emphasising that the product has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and by European Union regulators.

The urine test app scans the dipstick and analyses the colour changes against a chart

As the test can be done very easily at home, he believes it has the potential to save health systems "hundreds of millions of pounds" in clinician time and earlier diagnosis of diseases that would be far more expensive to treat later on.

The app and kit, which costs £9.99, has been used more than 100,000 times around the world, the company says. Pharmacy chain Boots is currently trialling the service in the UK, and the National Health Service is using it to monitor kidney transplant and diabetes patients.

The main advantage of a smartphone is that it has "huge computational power, a high-resolution screen, excellent cameras and is, importantly, connected and available worldwide," says Dr Andrew Bastawrous, co-founder and chief executive of Peek Vision, a tech company pioneering simple eye tests for developing countries.

About 36 million people in the world are blind, many from easily treatable diseases, he says. Earlier diagnosis could save the sight of the majority of these people.

Dr Andrew Bastawrous demonstrates the Peek Acuity app to his project team in Kenya

But in remote, poorer areas of the world, bulky and expensive medical equipment is hard to come by.

Peek Vision's eye test app, Peek Acuity, displays the letter E on the phone screen and this changes in size and orientation during the test.

The patient points in the direction he or she thinks the letter is pointing and the tester swipes the screen in that same direction. The app works out if the answer was right or wrong. The test results are stored in the cloud and sent to the nearest trained clinician.

"Our app is designed so that almost anybody can use it," says Dr Bastawrous, an academic and eye surgeon who works at the International Centre for Eye Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

"Training takes just a few minutes, so it can be used by non-specialists, including teachers, community leaders and general health workers."

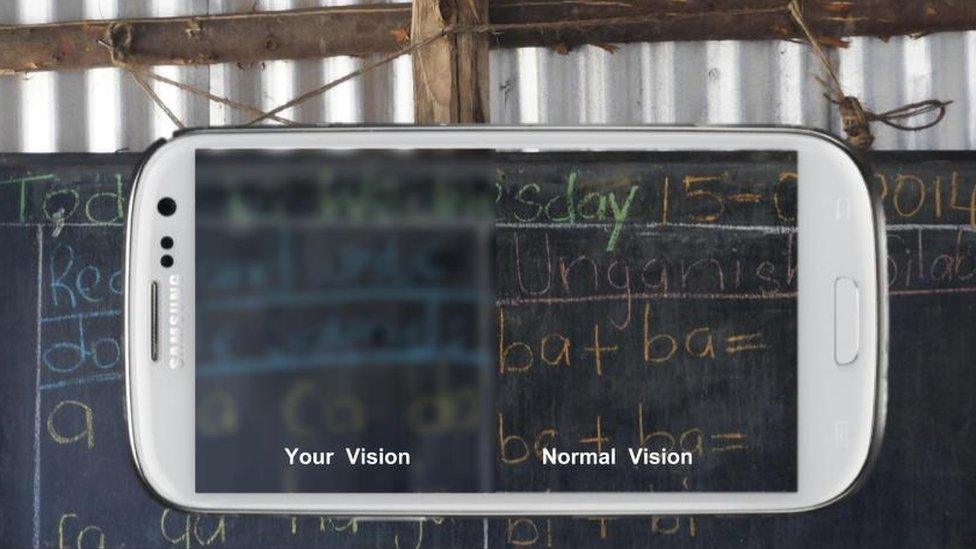

The app can simulate what the world looks like to someone with bad eyesight

The phone's camera can also simulate what the world looks like to the person tested, helping parents clearly understand why their child might need treatment, he says.

So far, more than 250,000 people have been screened in Kenya, Botswana and India, with the costs being picked up by partner charities and governments. The app has won clinical approval in Europe, and Dr Bastawrous says it is "at least as accurate as a conventional eye test".

"The ability to record data at the point of care, take images that could be analysed using artificial intelligence or by experts who cannot be everywhere at once, increases the possibility of universal healthcare being realised across the spectrum of healthcare specialities," he concludes.

There are plenty of other companies and researchers exploring the potential of the smartphone as a medical diagnostic tool, often in conjunction with add-on pieces of kit.

Accenture's Niamh McKenna says smartphone diagnosis has "great potential"

Cellscope, for example, has developed an attachment for the smartphone camera that enables parents to probe a child's ear and take a video of the inside, which is then viewed by a doctor remotely.

The idea is that parents can rule out false alarms and save on wasted trips to the doctor.

Meanwhile, research teams are developing plug-in sensors that can detect a range of diseases, from HIV to Ebola, from a small sample of blood. And attachments can turn the phone's camera into a microscope capable of examining red blood cells for signs of malaria.

"There have been some exciting developments in the evolution of the smartphone as a diagnostic tool," says Niamh McKenna, health lead at consultancy Accenture. "Clinical diagnosis on the move has great potential for application in remote areas.

"However, we need to remind ourselves that ultimately smartphones are being developed as consumer technology and not as medical devices," she adds.

"Trying to repurpose them in this way can lead to confusing consumer propositions and potentially come up against regulatory issues - like data protection."

But if cheap, portable and accurate diagnosis of treatable conditions saves lives as promised, the smartphone could become the most important invention of the last 20 years.

Follow Matthew on Twitter, external and Facebook, external